Stanford-led study reveals extent of labor abuse and illegal fishing risks among fishing fleets

A new modeling approach combines machine learning and human insights to map the regions and ports most at risk for illicit practices, like forced labor or illegal catch, and identifies opportunities for mitigating such risks.

Monitoring the world’s fishing fleets for labor abuse and illegal fishing can be as challenging as the oceans are vast, but new data could help companies and countries intervene more effectively. A Stanford University-led paper published April 5 in Nature Communications identifies the regions and ports at highest risk for labor abuse and illegal fishing and indicates two main risk factors: the country that a vessel is registered to, also known as its “flag state,” and the type of fishing gear the vessel carries onboard. The results offer policymakers and regulators a set of vessel characteristics and regions to pay more attention to when sourcing seafood.

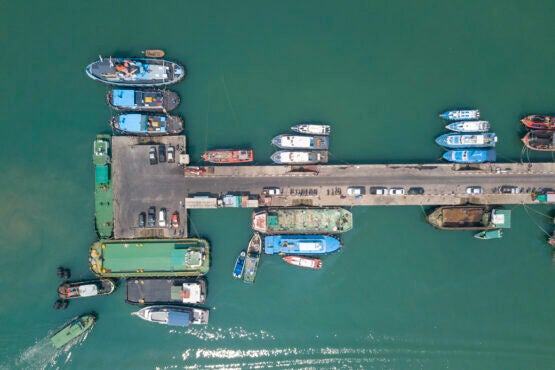

An aerial view of fishing vessels tied up to a pier. Vessels come into port to offload catches and exchange crew. Ports serve as critical hubs where officials can monitor and enforce legal frameworks that govern labor and catch. (Image credit: iStock / Akarawut Lohacharoenvanich)

“Surveillance on the high seas is innately challenging, so these data provide a critical first step in helping stakeholders understand where to look deeper,” said lead author Elizabeth Selig, deputy director of the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions. “We hope these findings can help to inform strategically expanded enforcement, focus development aid investments and increase traceability, ultimately lowering the chance that seafood associated with labor abuse or illegal fishing makes its way to market.”

Using an online survey of experts, the researchers also found that labor abuse and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing are globally pervasive: Of more than 750 ports assessed around the world, more than half are associated with risk of one or both practices. However, in addition to revealing the global extent of these risks, the study also highlights potential pathways to reduce these risks through actions at port that detect and respond to labor abuse and deter the landing of illegally caught fish.

“Major seafood companies are now able to understand where risks are greatest in order to help them meet their commitments to remove labor abuse and illegal fishing from their supply chains,” said co-author Henrik Österblom, science director at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, who heads the science team advising SeaBOS, an initiative that includes the world’s ten largest seafood companies. “These results can help them confront these challenges.”

Remote risk prediction

Given limited surveillance and enforcement capacity, the high seas – or the waters beyond a country’s jurisdiction – have long provided a safe haven for IUU fishing. Every year, millions of tons of fish are caught illegally. Vessels engaged in IUU fishing often also have labor abuses on board including subjecting workers to forced labor, debt bondage and poor working conditions.

The study team chose to assess risk, or the possibility that illegal activities might be happening in a specific area, rather than predict case numbers due to the challenge of identifying which vessels are involved in illegal activities at any given time and the need to manage risks more broadly across fleets.

To investigate risk, the authors paired human insights with big data. An anonymous survey distributed to experts from seafood companies, research institutions, human rights organizations and governments helped quantify the degree of certainty around whether particular ports were associated with either labor abuse or IUU fishing. Using machine learning, the team then combined survey responses with satellite-based vessel-tracking data curated by Global Fishing Watch to identify higher-risk regions associated with transshipment, where crew and catches are exchanged between vessels, and at sea.

For fishing vessels, coastal regions off West Africa, Peru and the Azores, Argentina and the Falkland Islands had higher risks for labor abuse and IUU fishing. The model also revealed that vessels registered to countries that have poor control of corruption, vessels owned by countries other than the flag state and vessels registered to China have a higher risk of engaging in illegal activities. Chinese-flagged vessels, comprising the world’s largest fishing fleet, dominated the data and were thus analyzed separately. For transshipment, certain fishing gear types – like drifting longliners, set longliners, squid jiggers and trawlers – were found to be higher risk.

The study also showed a strong presence of foreign-flagged vessels in fishing grounds thousands of miles away from where they bring their catch to port. This suggests that ports with weak monitoring standards can incentivize illegal activities far away, highlighting the need for coordinated regional action.

The promise of ports

All voyages begin and end in port. These bustling stopovers serve as critical hubs where officials can monitor and enforce legal frameworks that govern labor and catch. The study team analyzed the effectiveness of port measures for mitigating risks of these illegal practices. For labor abuse, they analyzed how long vessels spend in port, finding that riskier vessels have shorter port durations, which reduces the odds that port officials can intervene or that workers can access port services.

“Ports are one of the few places to identify and respond to labor abuse,” said Jessica Sparks, a fellow at the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions and associate director at the University of Nottingham Rights Lab. “We need to ensure that policies and practices allow fishers to access trusted actors and services at port so they can safely report on their condition.”

For IUU fishing, the team examined how vessel visits changed after the Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA) – which stipulates inspection standards, data exchange and port entry denial when appropriate for foreign-flagged vessels – entered into force in 2016. In the year after the PSMA took effect, the team found that fewer risky vessels visited countries that had ratified PSMA measures compared to countries that did not.

“Port state measures offer a lot of promise, but they need to be implemented effectively and, ideally comprehensively across regions, so that vessels cannot easily escape scrutiny by going to a port in a neighboring country,” said Selig. “We need regional ratification and effective implementation.”

Other co-authors from the Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions include Data Research Scientist Shinnosuke Nakayama and Lead Scientist Colette Wabnitz, who is also associated with The University of British Columbia. Other co-authors are affiliated with the Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University; the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University; Global Fishing Watch; The Pentland Centre, Lancaster University; and the University of Nottingham Rights Lab.

The research was supported by The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.