Stanford Earth Dean Steve Graham looks back on the first Earth Day

Stanford Earth Dean Steve Graham joined one of the thousands of rallies held in celebration of the first Earth Day. Now he discusses the event and his own expanding thinking about the planet and its history.

Fifty years ago this month, Steve Graham, now dean of Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, walked onto a meadow on his college campus in Bloomington, Indiana, and joined a rally for the environment.

Stanford Earth Dean Steve Graham on the historic Stanford campus in 2017. (Image credit: Steve Castillo)

Twenty years old at the time, Graham was one person among millions who participated in more than 12,000 events on college campuses, along city streets and in town squares and schools across the United States that day – April 22, 1970 – for the first celebration of Earth Day.

The boisterous, loosely organized affair was the brainchild of Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson, who gave a speech at Bloomington that morning in which he urged the crowd to think about Earth and what he called “the battle to restore a proper relationship between man and his environment” with a wide lens.

Graham had already begun to think about Earth and its resources in long time scales. As a child, he’d tagged along on wildcatting trips with a geologist uncle. “My mom let me go out with him when he was drilling wells, and I could sense the excitement of solving a problem,” Graham recalled recently. “It wasn’t that I was interested in looking for oil. I just became really intrigued by how Earth came to be the way it is now.”

But he was not yet steeped in the concerns that spurred Nelson to call for a national teach-in on the environment and inspired thousands of speeches and colorful demonstrations during the spring of 1970 – and that have animated Earth Day events each year since.

New awareness of environmental change

As a geology student, later as a research scientist for the oil industry and early in his 40-year career as a professor at Stanford, Graham said, “I was thinking fairly parochially and narrowly about my specific slice of geology – the history of the San Andreas Fault and the long-term evolution of the Earth system.”

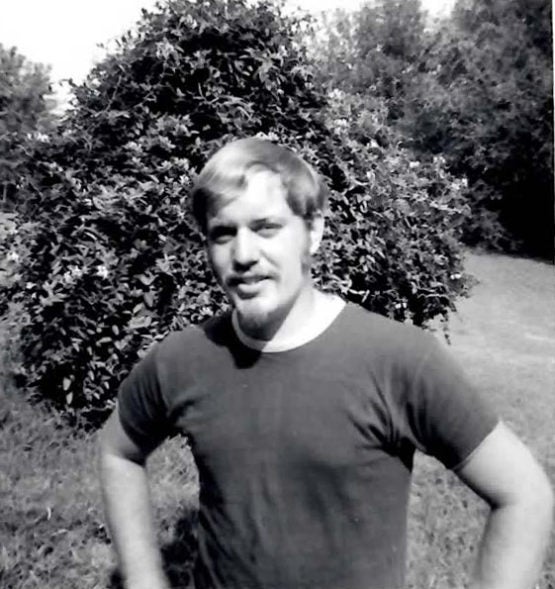

Steve Graham in his family’s backyard in Evansville, Indiana, in the summer of 1970, after returning home from a field season in southwestern Montana. (Image credit: Courtesy Steve Graham)

Over time his thinking changed. “It’s changed in part because of the changing nature of my responsibilities here in the school,” he said. Stepping into the role of associate dean, in 1999, afforded Graham a view of the breadth of work being done by colleagues throughout the school. He saw researchers illuminating how fluids flow within Earth – “usually oil and gas but with applications to water and geothermal.” He noted others taking advantage of advances in tomographic imaging to change the way scientists look at Earth in a very literal sense. “Now we approach Earth in the same way that medicine approaches the body,” Graham said. He gained new appreciation for how research at Stanford Earth had enhanced understanding of how plate tectonics works. And he began to notice “the important things that were developing at that time with regard to awareness of the changing environment.”

Part of this shift came through the school’s recruitment of a new cadre of faculty focused on environment and sustainability issues to join those researching Earth processes and energy resources. Some of the new faculty have added to our understanding of the relationship between environmental destruction and global pandemics, the impact of climate change on food production, options for adaptation in a warming world and how plants help to shape rainfall and temperature patterns.

Meanwhile, the undergraduate Earth Systems Program, launched in 1992, and the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources, started up a decade later, have charted a new path for education in environmental science and sustainability. More recently, the school opened an educational farm and a program dedicated to preparing students to lead sustainability efforts.

“There are of course technical and scientific contributions,” Graham said. “But quite aside from things that we do with, for instance, climate modeling, we increasingly have people in the school operating at the intersection of science and societal impact who are able to straddle across what had been a pretty hard boundary.” Earth system science Assistant Professor Marshall Burke, for example, is an economist whose research centers on how changes in the environment affect social factors such as human health, economic productivity and property values.

Challenges spring to life

Over time, Graham found his own “deep love for understanding the Earth” drew him more and more into the history of climate change. In his office on the historic Stanford campus, in March, he pointed above his desk to an oversized photograph of Torres del Paine National Park, in Chilean Patagonia, which he began visiting on research trips more than 20 years ago. The region has come to symbolize his broadening views.

“It’s a place of Andean condors and mountain lions. It’s stunning scenery – a reminder of the majesty of the natural world,” Graham said. “But at the same time, the local glaciers are melting like crazy. So, it brings to life the urgency of dealing with the environmental challenges that we face right now.”

Eighty million years ago, the rocks of Torres del Paine were part of the seafloor. “They’re no longer underwater,” Graham said. “We can look at them, walk around on them.” By studying these ancient deposits, geologists can gain insights about the modern-day deep ocean, and increasingly, find clues about what happened to marine life when oxygen levels in Earth’s oceans dropped catastrophically. That’s particularly relevant now, with ocean oxygen levels falling again in the face of global warming.

Opportunity to celebrate and mobilize

So much of the first Earth Day was adamantly physical: an up-close, in-person, sensory experience altogether inconsistent with the present time of global contagion. Some participants picked up roadside trash by the ton and dumped it on the steps of a courthouse. Others poured oil on an oil executive’s desk, hauled nets of dead fish through city streets, convened for folk music concerts or handed out daisies.

For now, the freeways are empty and the courthouse, closed. The executive is sheltering in place. In 2020, Earth Day happenings are necessarily online and close to home. But a point articulated in some of Nelson’s notes for Earth Day speeches cuts across the decades. The issue at hand, he said, “is more than just a matter of survival. How we survive is the critical question.”

In Bloomington on that day half a century past, Nelson urged his audience to strive for “a decent environment in its broadest and deepest sense,” free of ills ranging from poverty to war to disrespect for living creatures. Achieving that would require social, economic and political transformation. Tackling even the physical aspects of the environmental problem, such as polluted air and water, he argued, would demand understanding of the big picture.

“And the big picture is we live in a relatively insignificant planet that’s coursing through space. It’s a finite planet with a finite capacity to support life,” Nelson said. “It has a limited amount of resources; a thin envelope of air surrounding it, which is rapidly being polluted; a limited amount of fresh water; some minerals, some forests; a thin covering of topsoil.”

The implications of that planetary perspective have come into sharper focus for Graham along his journey through the geosciences. “It’s really been the impact of climate change, in terms of melting ice, increasing global temperature, that has an unavoidability about it that just demands everybody’s attention,” Graham said.

In the face of growing urgency to address climate change and sustainability, he added, Earth Day in its 50th year represents “an opportunity to celebrate the planet that we live on and, at the same time, to mobilize the broad public to take personal action and engage with environmental policy decisions being made in the U.S. and around the globe.”

Stephan Graham is the Chester Naramore Dean of the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, the Welton Joseph and Maud L’Anphere Crook Professor and professor, by courtesy, of geophysics and of energy resources engineering.