Academics is often a visual pursuit – reading journal articles, examining manuscripts, looking through a microscope. But some things can only be learned through sound. The boom of volcanoes, buzz of mosquito wings or tone of a person’s voice all convey information lost to a visual observer. The challenge in all of these is learning how to make sense of the sounds around us, in some cases with technology and in others by simply listening to one another more carefully.

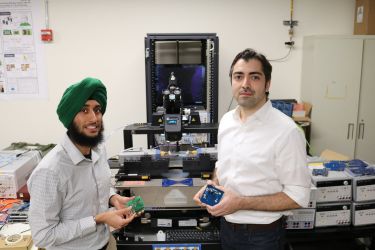

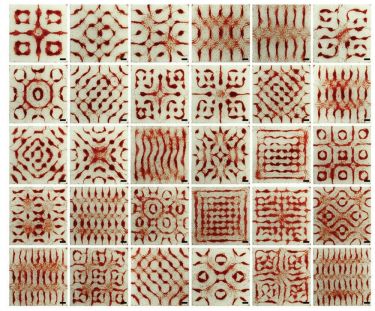

Beyond helping us interact with the world and with each other, sound can be an almost physical tool. Frequencies beyond the range of human hearing can wake up sleeping appliances and arrange heart cells in the lab. Sound waves can even be a means of peering into the body and diagnosing health conditions.

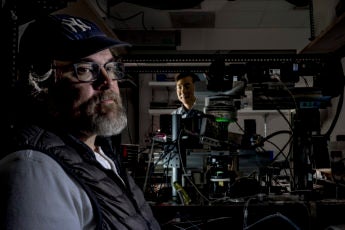

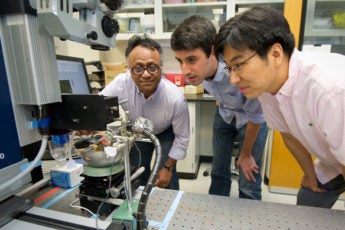

Stanford scholars from across medicine, engineering, social sciences and the arts are working together to interpret and manipulate this audible world, and to restore hearing to those whose ability is diminished. They’re even helping people learn to listen more carefully to each other.

Editor’s note: This page was first published July 2, 2018 and has been updated with new content.

Sound learning

The world is filled with pinging, buzzing, reverberating sounds that carry information. Rumblings that portend a volcano; underground vibrations elephants use to communicate; jet plane noises that, if quieted, could also improve power production from wind farms. This is some of the work underway at Stanford in which researchers are probing the world by listening:

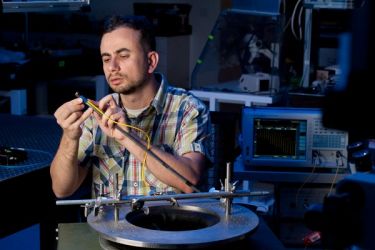

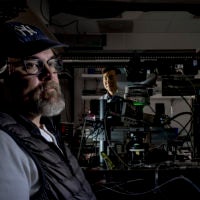

Sound tools

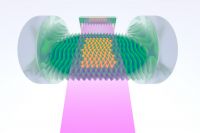

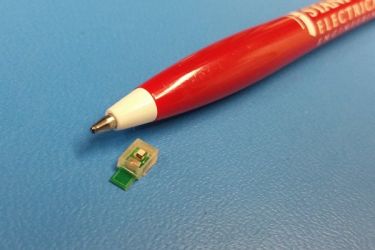

Invisible sound waves carry a physical force. They rattle against inner ear cells to create the sensation of sound, and similar waves can trigger devices to turn on, detect hidden tumors or even probe the seafloor. These waves hold power well beyond what we can hear.

Understanding through listening

It’s one thing to hear and another to listen. The act of listening and communicating can help ease troubled relationships, steer medical decisions and even bring the past to life. But it’s not always easy, which is why some researchers are trying to unravel how we listen and why it’s so important.

Restoring sound

Some people are born without the ability to hear, and adults older than 70 are more likely to have hearing loss than to have normal, healthy hearing. For those seeking help, better diagnosis and treatments are on the horizon both through improved technology and the possibility of one day regrowing damaged inner ear cells.