The virus that causes COVID-19 has been very good at mutating to keep infecting people – so good that most antibody treatments developed during the pandemic are no longer effective. Now a team led by Stanford University researchers may have found a way to pin down the constantly evolving virus and develop longer-lasting treatments.

The researchers discovered a method to use two antibodies, one to serve as a type of anchor by attaching to an area of the virus that does not change very much and another to inhibit the virus’s ability to infect cells. This pairing of antibodies was shown to be effective against the initial SARS-CoV-2 virus that caused the pandemic and all its variants through omicron in laboratory testing. The findings are detailed in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

“In the face of an ever-changing virus, we engineered a new generation of therapeutics that have the ability to be resistant to viral evolution, which could be useful many years down the road for the treatment of people infected with SARS-CoV-2,” said Christopher O. Barnes, the study’s senior author, an assistant professor of biology in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences and a scholar at Stanford’s Sarafan CheM-H.

An overlooked option

The team led by Barnes and first author Adonis Rubio, a doctoral candidate in the Stanford School of Medicine, conducted this investigation using donated antibodies from patients who had recovered from COVID-19. Analyzing how these antibodies interacted with the virus, they found one that attaches to a region of the virus that does not mutate often.

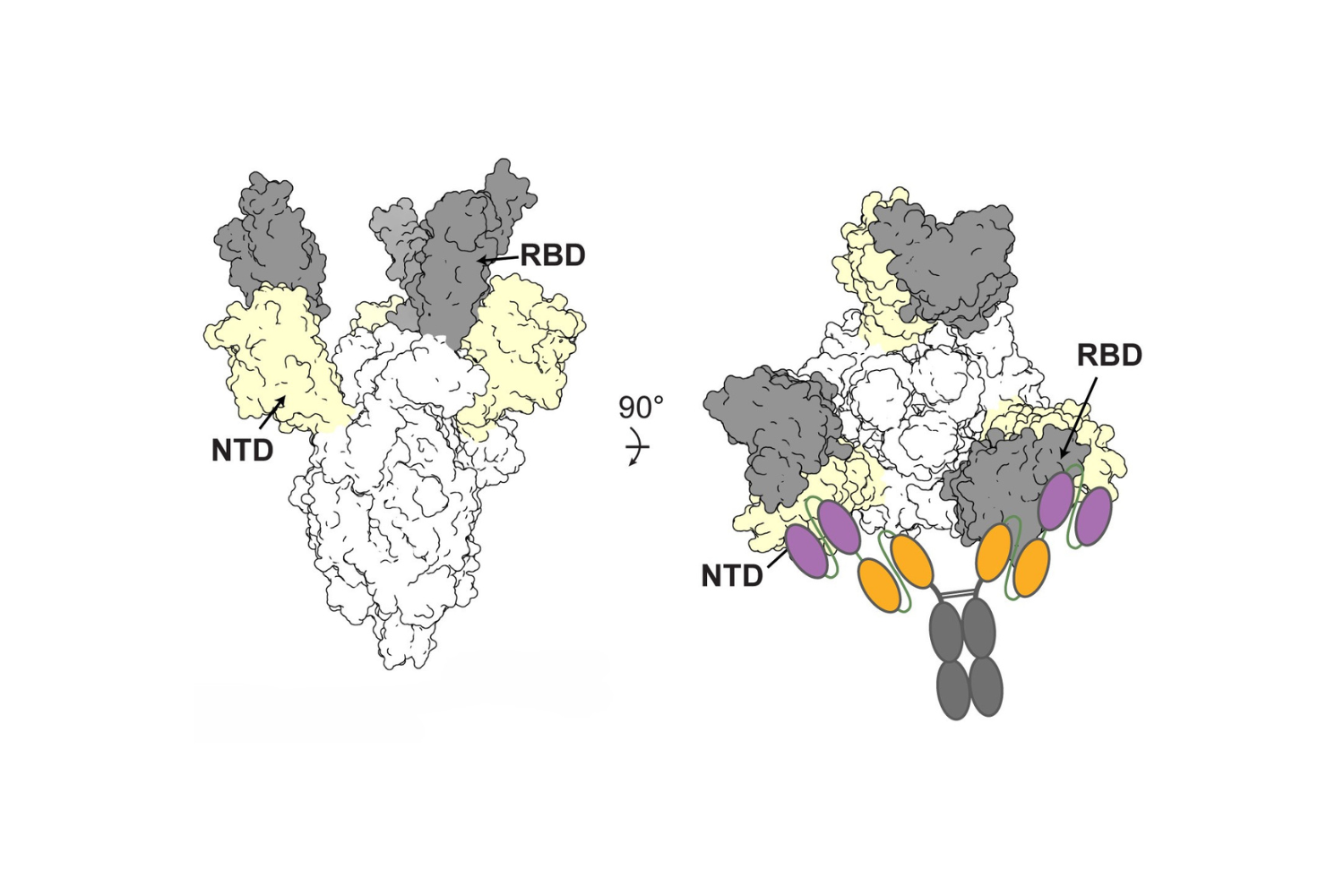

This area, within the Spike N-terminal domain, or NTD, had been overlooked because it was not directly useful for treatment. However, when a specific antibody attaches to this area, it remains stuck to the virus. This is useful when designing new therapies that enable another type of antibody to get a foothold and attach to the receptor-binding domain, or RBD, of the virus, essentially blocking the virus from binding to receptors in human cells.

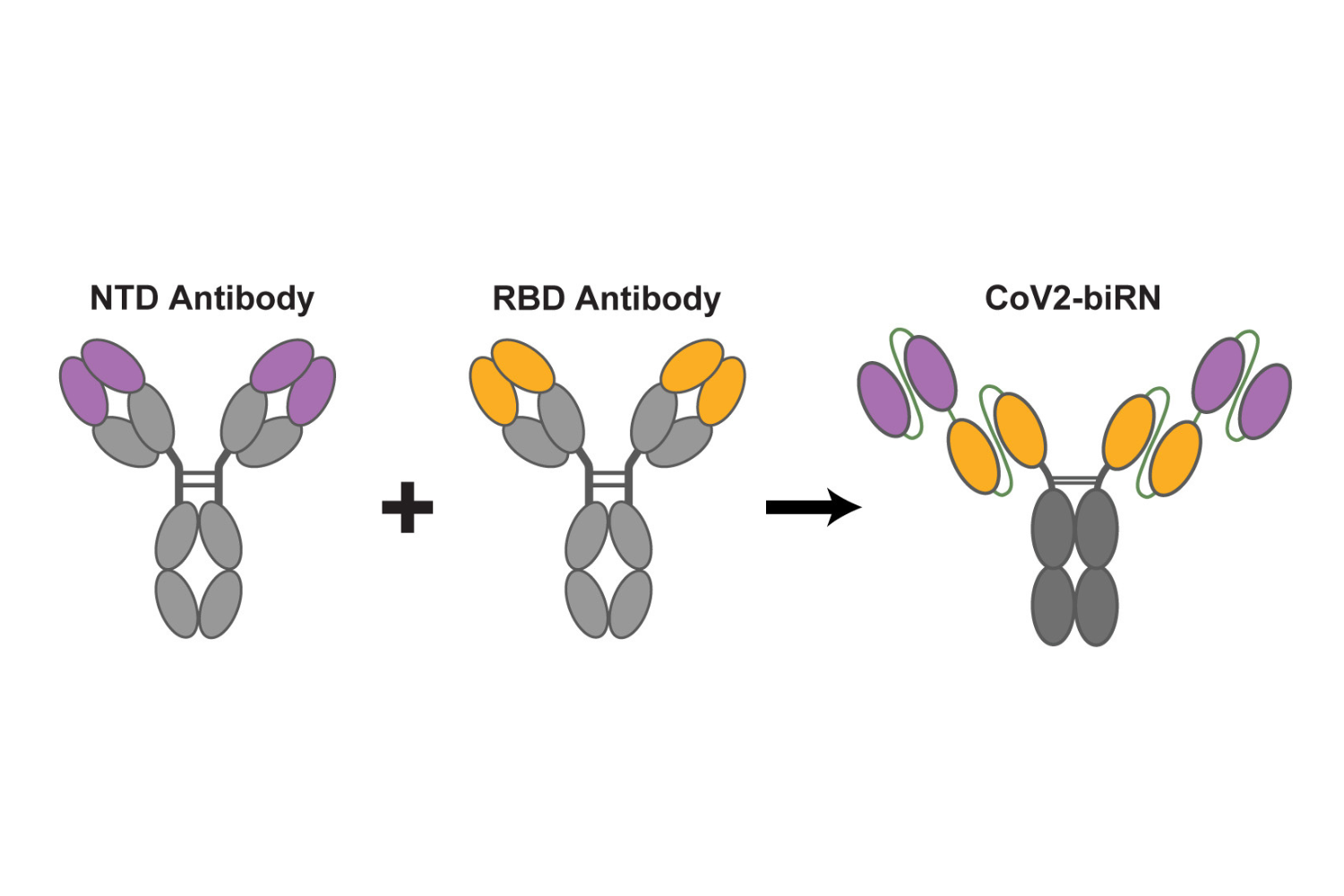

An illustration of the bispecific antibodies the Stanford-led research team developed to neutralize the virus that causes COVID-19. Named “CoV2-biRN,” these two antibodies work together by attaching to different areas of the virus.

The bispecific antibodies target two areas of the virus: One attaches to the “NTD,” or Spike N-terminal domain, an area on the virus that does not change very much. This allows the second antibody to attach to the “RBD,” or receptor-binding domain, essentially preventing the virus from infecting human cells. | Christopher O. Barnes and Adonis Rubio using Biorender stock images

The researchers designed a series of these dual or “bispecific” antibodies, called CoV2-biRN, and in laboratory tests they showed high neutralization of all the variants of SARS-CoV-2 known to cause illness in humans. The antibodies also significantly reduced the viral load in the lungs of mice exposed to one version of the omicron variant.

More research, including clinical trials, would have to be done before this discovery could be used as a treatment in human patients, but the approach is promising – and not just for the virus that causes COVID-19.

Next, the researchers will work to design bispecific antibodies that would be effective against all coronaviruses, the virus family including the ones that cause the common cold, MERS, and COVID-19. This approach could potentially also be effective against influenza and HIV, the authors said.

“Viruses constantly evolve to maintain the ability to infect the population,” Barnes said. “To counter this, the antibodies we develop must continuously evolve as well to remain effective.”

For more information

Additional Stanford authors include biology undergraduate Megan Parada; biology staff scientist Morgan Abernathy; life science researcher Yu E. Lee; biology lab technician Michael Eso; biophysics doctoral student Gina El Nesr; and former lab technicians Israel Ramos, Teresia Chen, and Jennie Phung. Barnes is also affiliated with the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub.

Rubio, BS ’21, is also affiliated with the Department of Biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

This work also includes co-authors from Rockefeller University, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This research received support from the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Pew Biomedical Scholars Program, and Rita Allen Foundation.

Rockefeller University has filed a provisional patent application in connection with monoclonal antibodies described in this work on which co-authors Zijun Wang and Michel C. Nussenzweig of Rockefeller University are inventors (U.S. patent 17/575,246). Co-authors Jesse D. Bloom of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center consults for Invivyd, Apriori Bio, the Vaccine Company, GSK, and Moderna. Bernadeta Dadonaite, also of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, consults for Moderna. Bloom and Dadonaite are inventors of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center-licensed patents related to viral deep mutational scanning.

Media contact

Sara Zaske, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: szaske@stanford.edu