Curious objects around Stanford campus

Witness to more than 130 years of history, the Stanford campus is full of interesting – and in some cases, mysterious – items, dispersed throughout the grounds. With abundant help from the Stanford community, Stanford News highlights a few.

Whether walking to class or merely wandering, people can encounter all manner of interesting objects around the Stanford campus. Some are out in the open, others are rarely seen by people outside certain departments or majors – and some are a bit of both, hidden in plain sight.

With the help of colleagues around campus, Stanford News has gathered a collection of some of our favorite campus curiosities and the stories behind them. (Well, behind most of them…)

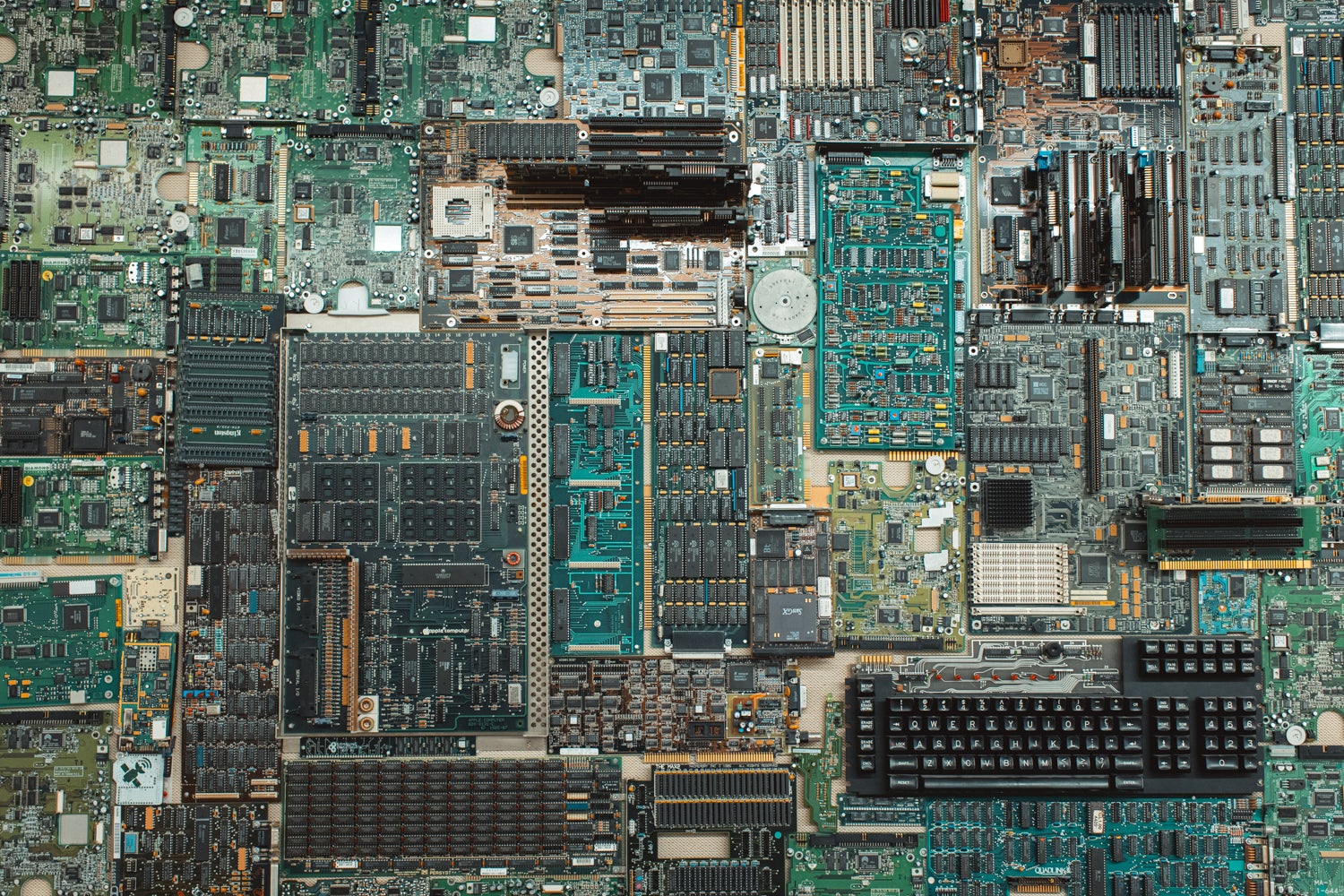

The ‘Mother of All Boards’

This wall hanging was created by Denise Murphy, a staff member in the Department of Electrical Engineering for 30 years. She created it around 1999, the first year that the Packard Building was in use, as a Christmas surprise. The “Mother of All Boards” – a play on the word “motherboard” and the phrase “mother of all wars” – is composed of printed circuit boards recycled from obsolete servers and computers from the department.

John Gill, associate professor of electrical engineering, emeritus, who donated many parts to this project said, “Over the past two decades, I have encountered many visitors admiring the board and have been proud to point to the creator’s office only a few feet away.”

Drinking fountains on Quad

Within the arcades of the Main Quad, four tiled drinking fountains can be found near buildings 20, 30, 80, and 90. One more is behind the entrance to Memorial Court, across from the Oval. The fountains in the Quad – three of which feature images of lamps – were donated by the classes of 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1927.

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

The fountain at Memorial Court was the result of a donation from Anna Hatch McAllister to memorialize her son, Harold Hatch McAllister, who drowned in 1925. Harold was a member of the Class of ’26 and the fountain was funded through the money he had saved for school. In a 1926 Stanford Daily article, Anne Hatch McAllister said, “It is entirely fitting that that money should be devoted to a memorial for him at the college which he loved.” The fountain was designed by Eri Richardson, AB 1907 in botany, who also designed the class fountains, and features a ship at full sail, representing a young person’s journey toward the rest of their life.

Original Google storage server

Sitting at the terrace level in the Huang Engineering Center is a computer server covered in toy construction bricks. The Huang Engineering Center Innovations Tour summarizes its history:

In 1996, PhD students Sergey Brin and Larry Page invented the PageRank algorithm. Their work in this area was supported by Professors Hector Garcia-Molina, Rajeev Motwani, Jeffrey Ullman, and Terry Winograd. The algorithm ranks web pages that match search terms by assessing breadth and depth of public interest in that web content. Because much disk space was needed to test PageRank on actual World Wide Web data, Sergey and Larry assembled 10 of the largest drives available (4 gigabytes each) into this low-cost cabinet, whimsically decorated with [plastic construction] bricks. Their software could then index 24 million pages a week (at the time, a massive number).

As a result of their initial work at Stanford, the two founded a company called Google in 1998. By 2008, Google reported that its thousands of servers had indexed more than a trillion unique pages.

HP garage replica

Not far from the server is a replica of the HP Garage. From the Huang Engineering Center Innovations Tour:

As electrical engineering undergraduates and graduate students at Stanford in the 1930s, William Hewlett and David Packard encountered three influences that would guide the rest of their lives: the excitement of technology, an entrepreneurial spirit in the emerging field of electronics, and each other’s friendship. With help and inspiration from Professor Fred Terman, Packard and Hewlett co-founded an electronics company in 1939 in a garage on Addison Street in Palo Alto. They didn’t have much – a little more than $500 and a used drill press. A prominent fixture of the garage was a simple, gray workbench, where the pair of engineers toiled to produce whatever “would bring in a nickel.” One of their earlier customers was the Walt Disney Co., which bought oscillators for the classic movie Fantasia.

Stanford griffins

Situated at the crossroads of Campus and Palm drives are two head-turning statues known as the “Stanford griffins.” (Although unlike a traditional half-lion, half-eagle griffin, they are lions with eagle wings.) The griffins date back to about 1870 and were created by sculptor Eugène-Louis Lequesne, likely for a fountain featured on the estate of former Stanford trustee Timothy Hopkins, who is also the namesake of Hopkins Marine Station.

The statues were later positioned outside the men’s gymnasium at the corner of Campus Drive and Galvez Avenue. When that structure was demolished in 2004, the griffins were put into storage. In 2018, they were given a new home at the head of a path that leads to the Stanford Mausoleum. A more thorough account of the history of the Stanford griffins was published in Stanford News in recognition of their latest reemergence.

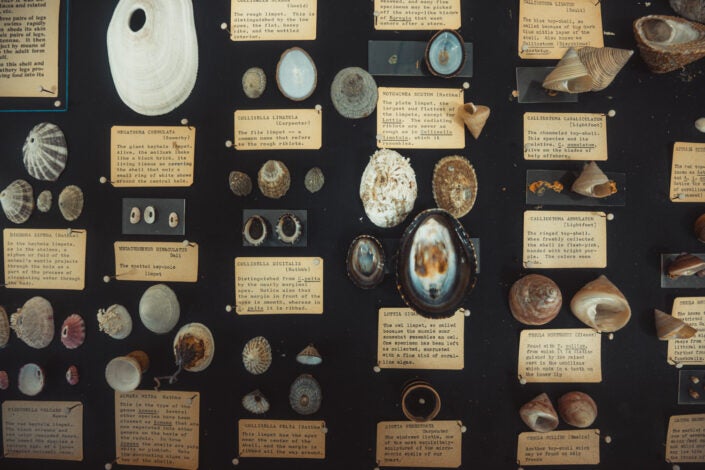

Invertebrate collection

The 2nd floor of the Geocorner features an extensive collection of invertebrates and mollusks from Puerto Peñasco, which borders the Gulf of California. Most of the specimens included were collected in 1941. This collection was assembled by Myra Keen, who was a volunteer on the 1941 expedition. With many male faculty gone during World War II, Keen helped teach courses in paleontology. By 1965, she was a full professor.

Geologist Don Lowe, the Max Steineke Professor in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, took a curatorial methods course taught by Keen when he was an undergraduate. “One highlight of the course was that we had to take several delicate shells and pack them for shipment,” said Lowe. “Professor Keen would then take our packages, climb up a stepladder, and slam them as hard as she could down onto the floor. After doing this several times, she had us open the packages to see if the shells had survived intact or were badly damaged. It was a tough test to pass.”

Lowe said that after the Loma Prieta earthquake the Geology Building had to be evacuated, and most of the shells in Keen’s collection were donated to California museums. “We retained the cabinet with California coastal invertebrates because of the many field trips and excursions that persons from the department take to the coast,” said Lowe.

Giant clam

Perhaps the most curious of these curiosities is a giant clam near the stairwell on the 2nd floor of the Geocorner. Multiple faculty members agree that it is, as labeled, Tridacna gigas, and could very well be from the Philippines, also as labeled. They, too, agree that it’s oriented inaccurately compared to how it would have sat in life – offering a toothless smile rather than gaping toward the sky.

What is less clear is how this ocean giant got from the Philippines to a Stanford hallway, where it sits nestled between a wall phone and a water pipe. It’s possibly another item from Myra Keen’s more extensive collection but that’s unconfirmed. If you know about this clam, please share!

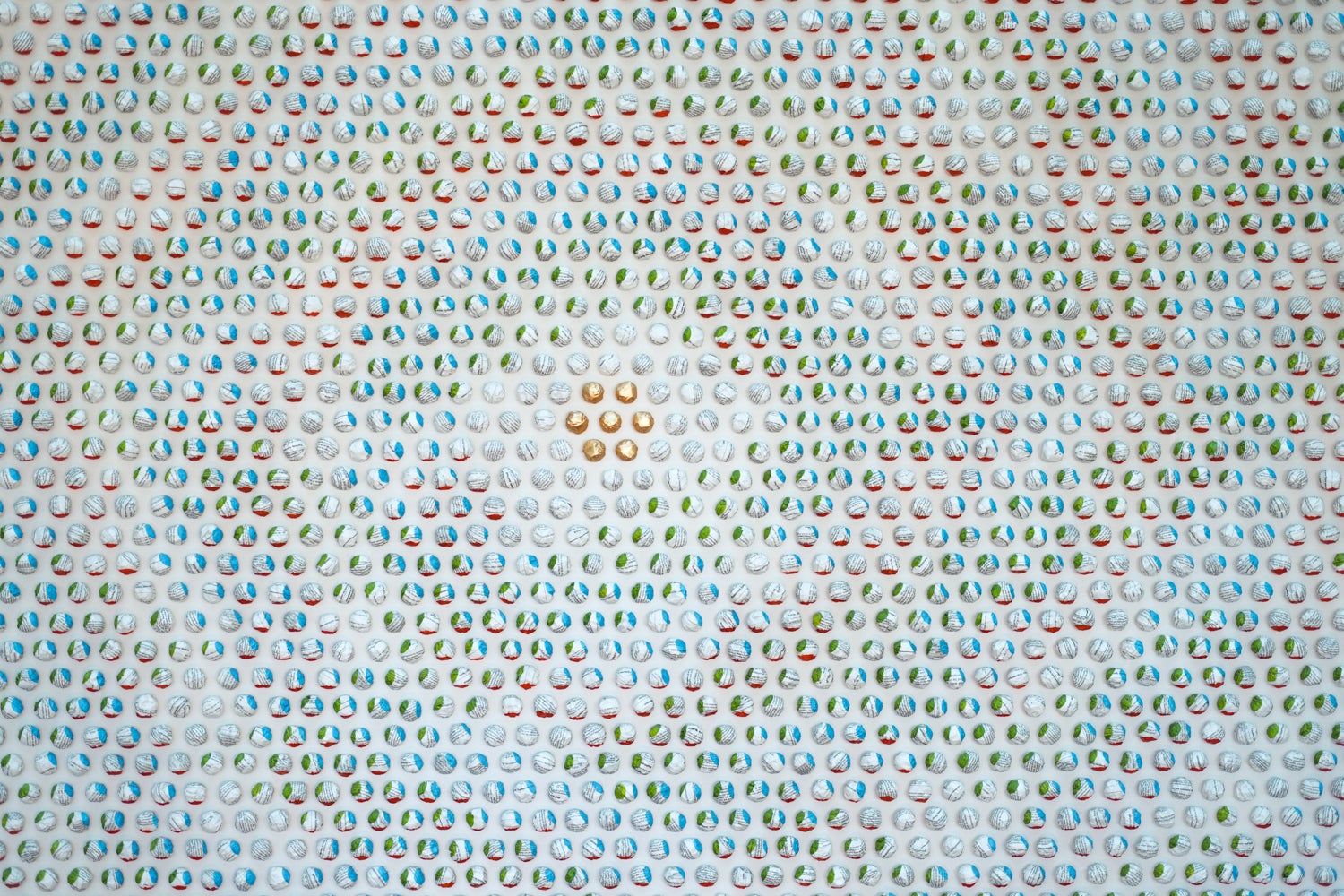

‘The Spitball’

Formally unnamed, the wall hanging in the Shriram Center for Bioengineering and Chemical Engineering is known by some as “The Spitball.” It was designed to represent the concept of “reaching your goal” when Shiram was first being built and decorated.

There are gold balls at the center of the piece and the balls around it form the walls of a maze. “The idea was that everyone has at least one goal and that there are easy or hard ways to achieve it,” said Curtis Frank, the W. M. Keck, Sr. Professor in Engineering, Emeritus. “The balls of the maze were dipped in different colored paints such that, when viewed from different perspectives, one could see either no path to the goal or some more-or-less clear path.”

The paper balls that make-up this work are made of crumpled pages of an actual Stanford publication called Courses and Degrees. “So, as students walk to/from the classroom they are literally experiencing the entire Stanford course catalog,” said Drew Endy, the Martin Family University Fellow in Undergraduate Education and associate professor of bioengineering in the schools of Engineering and of Medicine, who was part of a group that consulted on various design aspects of Shriram. “Of course, this leads, informally, to the unofficial use of ‘spitballs.’”

Endy also hints at some other possible hidden messages in the work, including an ode to the value of “bottom-up” work. But, in the end, the details of the piece are probably best summed up by his description of the goal at its heart: “What’s at the center? Meaning? Knowledge? It’s art. We can’t tell you.”

Industrial models

An impressive cutaway model of an industrial creation welcomes people entering the front door of the Mechanical Engineering Research Lab (MERL). According to its label, it is a ½-in-to-1-ft scale model of a Taylors Cornish beam engine from 1840.

This model, and another down the hall, were gifts from a Stanford alum.

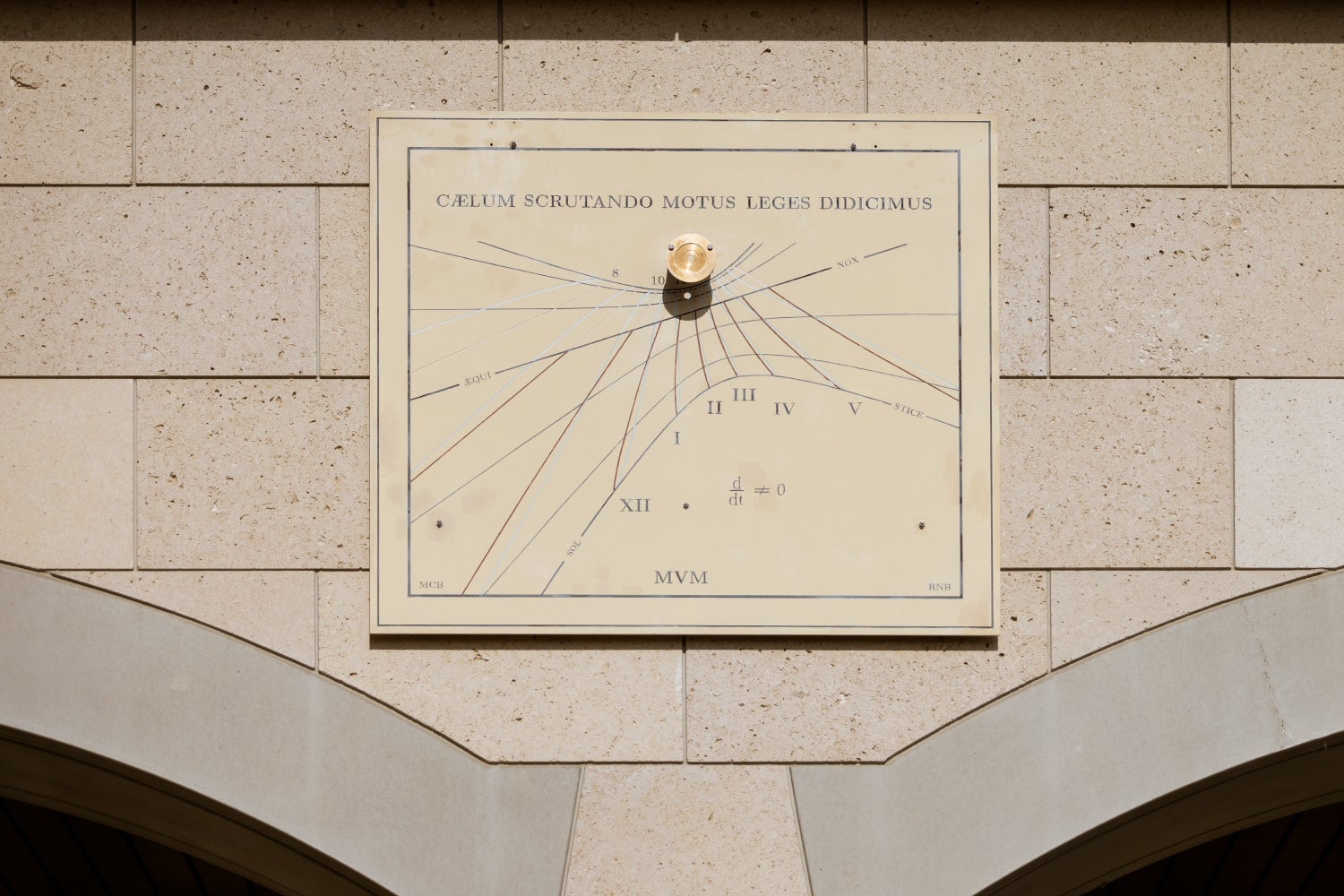

Sundial

This unusual wall-mounted sundial was originally installed on the Terman Building in 1997 by Ronald N. Bracewell, who was the Lewis M. Terman Professor of Electrical Engineering, Emeritus. It was built by Bracewell and his son Mark, who were inspired by a sundial that “once graced the Tower in the Agora in Athens,” according to the associated plaque.

As the School of Engineering described, “The disc creates a shadow with a bright dot of sunlight in the center for telling both time and season. The hour lines are laid out not as straight lines, but as analemma curves (the first eight patterns of the sun’s seasonal movement), with spring colored in green, summer in red, autumn in orange, and winter in blue.”

In 2013, according to a post in the Stanford Libraries Blog, the sundial was re-mounted on the south side of Huang Engineering Center.

Mineralogical collection

Gordon Brown, the Dorrell William Kirby Professor, Emeritus, at Stanford and professor emeritus of photon science at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, has been in charge of the Branner Library foyer mineral display since its inception in the late 1970s. Brown described the arrangement of the minerals as “artistic,” a choice that once elicited a gentle critique from a visiting mineralogy professor “for not grouping the specimens according to their classification based on James Dwight Dana’s system of minerals.”

The display began with the mineral collection of Edward Swoboda, a jeweler in Beverly Hills, California, and a world-class mineral collector. Swoboda was a friend of Brown’s and of Richard H. Jahns’, dean of the School of Earth Sciences at the time the display was first established. Swoboda offered to loan Stanford his mineral collection if Stanford would build display cases that would protect the specimens from theft. At Brown’s request, Dean Jahns provided the funds to build the display cases. Swoboda’s collection consisted of “about 150 mineral specimens and included eight specimens that were the finest examples of each of those eight mineral species in the world; i.e., ‘world beaters,’” said Brown.

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

When Swoboda sold his collection, Brick Stang, a local mineral dealer, offered to loan Stanford a collection of beautiful pink tourmalines from Afghanistan. These, according to Brown, had been smuggled out of Afghanistan on the backs of donkeys during its occupation by the Soviet Union. The tourmaline specimens were sold by Stang in the late 1980s and replaced by mineral specimens from the collection of Demetrius Pohl, PhD ’84 in geochemistry. In addition to the mineral specimens on loan from Pohl, the Branner Library mineral display also contains about 50 mineral and gem specimens that are owned by Stanford University.

The funds for the cylindrical display case that rises through the center of the spiral staircase were donated by Howard Platt, AB ’30 in general engineering, and his wife. The design was suggested by Brown.

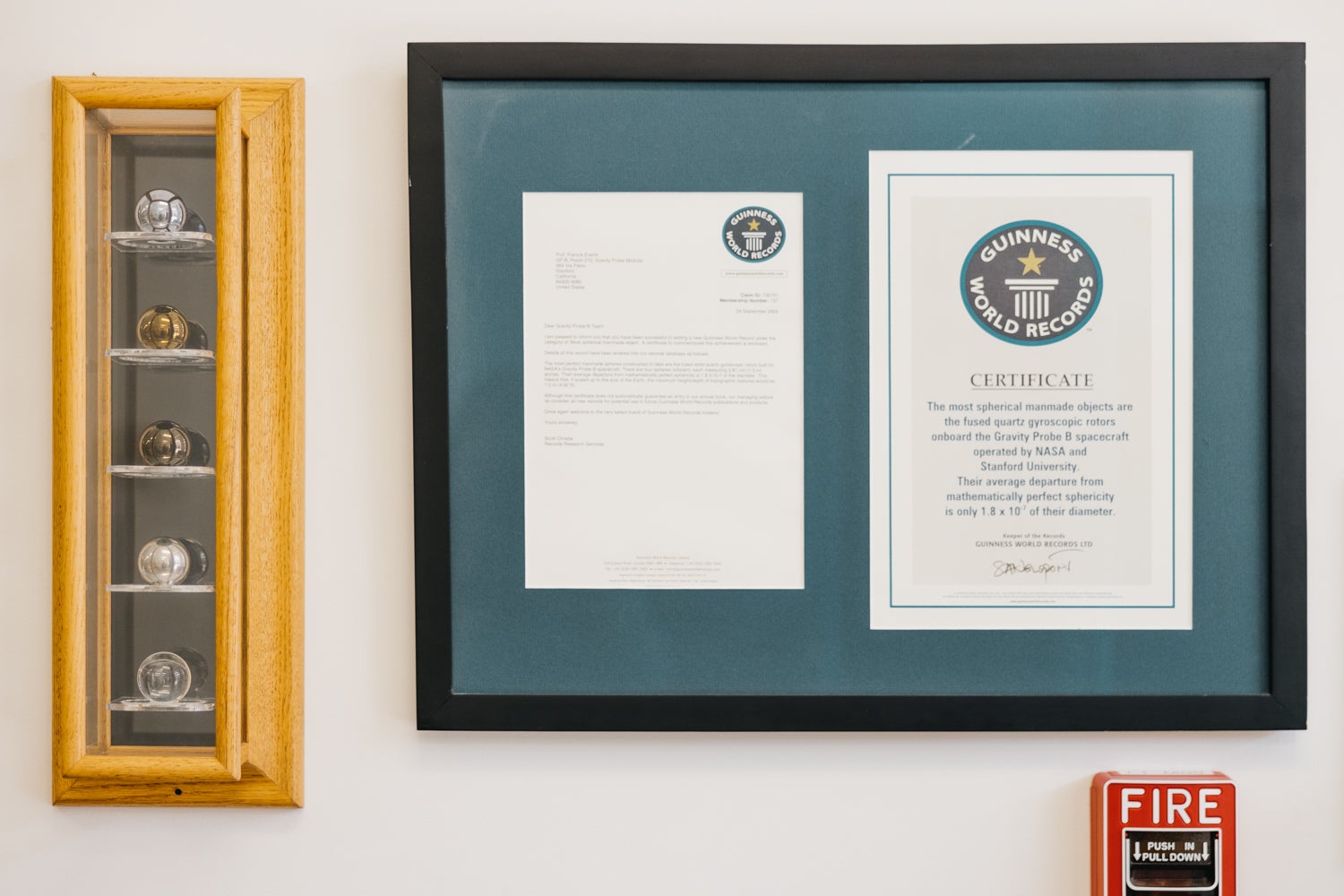

Gravity Probe B

Throughout the halls of the first floor of the Physics and Astrophysics Building, people can find objects related to Gravity Probe B. Gravity Probe B was a Stanford physics and engineering experiment led by Francis Everitt, professor emeritus at the W. W. Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory at Stanford. The project “was designed to measure two key predictions of Einstein’s general theory of relativity by monitoring the orientations of ultra-sensitive gyroscopes relative to a distant guide star,” according to the project’s Stanford website. The project, which was funded and sponsored by NASA, ran from 1963 to 2008 with the final results published in Physical Review Letters in 2011.

Gravity Probe B did confirm the two predictions, which Stanford News described in 2011 as follows: “The first is the geodetic effect, or the warping of space and time around a gravitational body. The second is frame-dragging, which is the amount a spinning object pulls space and time with it as it rotates.”

Among the many Gravity Probe B objects in the Physics and Astrophysics Building is a case of spheres that were designed to be the center of the probe’s ultra-precise gyroscopes, accompanied by a letter and certificate. In September 2004, the letter acknowledged that these gyroscope rotors had set a Guinness World Record. “The most spherical manmade objects are the fused quartz gyroscopic rotors onboard the Gravity Probe B spacecraft operated by NASA and Stanford University,” says the citation certificate. “Their average departure from mathematically perfect sphericity is only 1.8 x 10-7 of their diameter.”

Garden pond at Kingscote Gardens

Sarah Howard was the widow of Burl Estes Howard, a professor of political science who died suddenly. Seeing that Sarah Howard was left with three children and no income, Stanford President Ray Lyman Wilbur let her lease the land from the University to manage the Kingscote Gardens Apartments. The apartment building opened in 1917 and remained with Howard family descendants until Stanford purchased it and converted it into administrative offices.

The pond was built in 1926, with Sarah Howard’s input. The bridge over the pond is a Japanese design, while the fountain and cypress trees allude to Italian style.

All images by Andrew Brodhead