Stanford senior examines popular theater in London during WWI

Senior Holly Dayton analyzed popular theater plays in London during the time of the Great War as part of her history honors thesis research.

While she was wandering through a bookstore at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival a few years ago, Holly Dayton’s eye was caught by a book about the history of performances in occupied France during World War II.

Holly Dayton (Image credit: Courtesy Holly Dayton)

Dayton, who already had an interest in the cultural and economic significance of the theater, devoured the book over the following week. It stoked her curiosity about wartime theater in England, whose art scene she especially admired.

Dayton’s passion for theater and history has taken the form of an honors thesis that took the Stanford senior across the Atlantic Ocean last summer to the United Kingdom, where she immersed herself in England’s theatrical past.

“I think we’ve had a pretty simplistic and limited understanding of what theater was about during World War I,” said Priya Satia, associate professor of history and one of Dayton’s advisers. “By looking at the more ephemeral, popular performances of that time, Holly has been able to uncover a pretty different view about what theater meant then.”

Dayton, who is pursuing a major in history and a minor in theater and performance studies, said most of the available research centered on a narrow slice of war-themed plays. So she focused on the period’s popular musicals and musical revues, which are shows consisting of songs and dances tied together with a very loose plot. Dayton said both of those kinds of performances represent a specific subset of theater that hasn’t been studied much by historians and has been largely ignored by past and present theater critics, who have dismissed them as lowbrow art.

Dayton argues that the works she examined are powerful sources of cultural and historical evidence.

“Just because those plays were escapist or fluffy or deemed ‘bad theater’ doesn’t mean we should discount or not study them,” she said. “Even in times of war, people continued to come to the theater and watch these productions. It was a cultural phenomenon that can help us understand the people and the world in which they lived.”

London theater scene

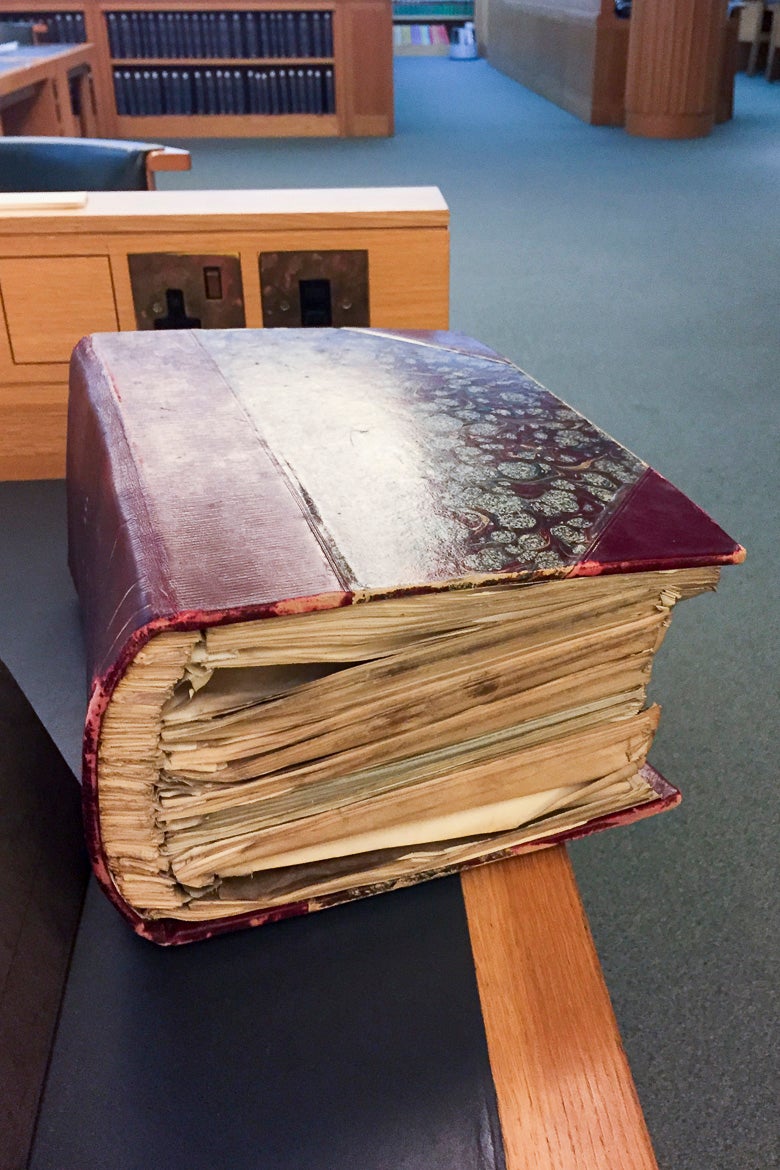

Dayton, a 2016-17 Hume Fellow at the Stanford Humanities Center, spent three weeks in England with the help of an Undergraduate Advising and Research Major Grant from Stanford in order to examine primary sources at the British Library in London and at the Theater Collection at the University of Bristol. She read and analyzed 42 plays and the censoring notes they received from the Office of the Lord Chamberlain, as well as hundreds of newspaper articles and reviews of those plays.

Senior Holly Dayton studied this collection of plays from 1914 to 1918 at the British Library as part of her history honors thesis research. (Image credit: Courtesy Holly Dayton)

Dayton, who also serves as the executive producer of the Ram’s Head Theatrical Society at Stanford, found that the musical revues reveled in grandiose, eccentric performances, often including all-female ensembles known as “beauty choruses” who danced in revealing clothing. The subject of war was largely avoided in these performances except for rare instances where the theme seeped into the plotlines of certain plays in a random, disjointed way, Dayton said.

For example, one play, set in London, featured a brief scene in which two actors playing German detainees express their gratitude toward the British government’s compassionate treatment of them, Dayton said.

“It seemed to me like an unnecessary, politically contentious thing to discuss in the theater,” Dayton said. “But through this example we can sense how the experience of war affected the public in exciting, patriotic and complicated ways.”

Dayton also traced the successes and hardships of a small group of women who leased and managed theaters in London before and during the war. Financing and administering theater productions were rare jobs for women at that time because of persisting gender inequalities such as disparate conditions for male and female loan applicants at banks.

“We usually think of war as a time when women had more opportunities,” said Satia, whose research has focused on the Great War and modern British history. “But it’s much more complex.”

The London theater scene is different today. The productions are significantly subsidized by the government, relieving theater managers from the financial pressures associated with their World War I predecessors. Also, the style of the musical revues Dayton studied has largely died out, she said.

“The theater we see today has the potential to show more artistic expression without feeling at the mercy of economic and social forces,” Dayton said.

Dayton, who plans to pursue her graduate education at the University of Cambridge, said she loved her research experience and the skills she gained. She hopes to continue to research plays and develop her academic career in the area of dramaturgy.

“It was exhilarating to be able to see and hold primary sources in my hands,” Dayton said. “It was an opportunity to really engage with the academic community as an independent academic myself.”