Wilfred H. Stone, Stanford professor emeritus of English, dies at 97

Stone was known for his knowledge of 19th- and 20th-century British literature, particularly the works of E.M. Forster and the Bloomsbury Group, and his commitment to the improvement of undergraduate education.

Professor Emeritus Wilfred “Will” Healey Stone, 97, died June 11 at his home on the Stanford campus, where he had lived for more than five decades. He joined the Stanford faculty in 1950 after earning his PhD from Harvard University, and served in the Department of English for 36 years.

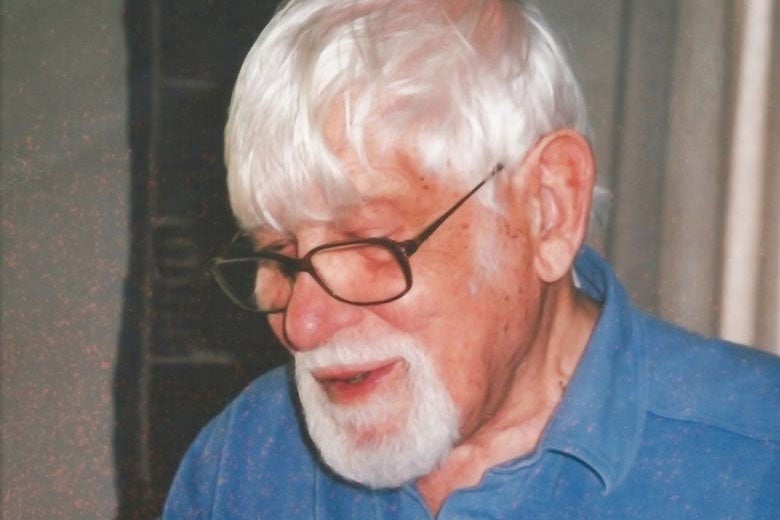

Wilfred H. Stone is remembered for his innovative contributions to Freshman English and outstanding service to undergraduate education. (Image credit: Courtesy Nancy Carleton)

Stone’s specialty as a teacher and scholar was Victorian and modern British literature, areas in which he developed nearly 20 courses and seminars, with a focus on E.M. Forster and other Bloomsbury writers.

He published two books on the fiction of these periods: Religion and Art of William Hale White (Mark Rutherford) in 1954, and The Cave and the Mountain: A Study of E.M. Forster in 1966. The latter won the Commonwealth Club of California Gold Medal and the Phi Beta Kappa Christian Gauss Award in literary criticism.

Stone was one of the first in the United States to pioneer Bloomsbury as its own academic subject, “a dubious distinction,” as he called it.

Stone remained dedicated to improving undergraduate literacy and education, and made it an integral part of his mission as a professor. One of his key concerns was the “decay” of the English language caused by TV jargon and lack of writing practice in high school English instruction.

During the 1955-56 academic year, Stone led a reshaping of Freshman English at Stanford into an engaging program that encouraged many students to continue pursuing their interests in writing and literary studies. He taught with enthusiasm in the program, and later became the director of freshman composition.

In 1962, Stone received the Lloyd W. Dinkelspiel Award for his innovative contributions to Freshman English and outstanding service to undergraduate education at Stanford.

He articulated his concerns for undergraduate education in a pair of anthologies and a book on prose style, as well as in initiatives he introduced in residential education. In 1954, he and Robert Hoopes, also a member of the English Department at the time, published Form and Thought in Prose, an anthology of teachable readings for Freshman English.

As Faculty Master (now “resident fellow”) of Stern Hall’s Muir and Burbank houses, Stone implemented a program of student-faculty interaction and education in residence halls and in his own advising, which became the precursor to the residential life programs that have since emerged.

He delivered keynote addresses at universities and high schools around the country.

Stone was the re-founder and faculty advisor of the student literary magazine Sequoia, and published many of his own essays in the Stanford Daily and other campus publications. In a 1961 article in the Stanford Review titled “No Time for Novels,” Stone argued the practical and realistic reasons to value – and make time for – the novel during a time when, he said, many people considered literature a frill compared to Fidel Castro and the stock market.

Stone was selected for a yearlong residency at the Stanford-in-Italy campus in Florence in 1966-67, based on his ability to bring European literature to life for his students.

Inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement, he taught one summer at a Freedom School in Jackson, Mississippi. On the Stanford campus, he was a leading faculty member in teach-ins to mobilize opposition to the Vietnam War, and remained committed to issues of peace and social justice.

After his retirement in 1986, Stone continued contributing letters and articles to the Stanford Daily, The Sewanee Review and elsewhere. One essay, “The Balloon Man,” won the 2007 Monroe K. Spears Prize for best essay published in The Sewanee Review that year. The essay, along with many of his other articles, is available on Stone’s blog, run by his stepdaughter, Nancy Carleton.

The Wilfred Healey Stone Papers are archived at the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford, including correspondence and interviews with E.M. Forster, Clive Bell and other members of the Bloomsbury Group.

In his youth, Stone served as a U.S. Navy pilot from 1942 to 1945, and earned his bachelor’s (cum laude, 1941) and master’s (magna cum laude, 1946) degrees in English from the University of Minnesota. He received his PhD from Harvard in 1950. He was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship for study at the University of London in 1949, as well as two Guggenheim Fellowships after joining the Stanford faculty.

Stone married Cary Lee Laird, the mother of his two children, in 1954; they divorced in 1971. In 1985, he married Margaret Aiken, who passed away in 2003. His ashes will be buried alongside hers at Alta Mesa Memorial Park in Palo Alto.

Stone remained active in the Peace and Social Justice Committee at the First Congregational Church of Palo Alto. It was there in 2008 that he met Ruth Carleton, with whom he spent the last six and a half years of his life.

Stone could “argue with humor and in the light of sweet reason, yet without compromise of his own firmly held convictions,” wrote his colleague Larry Ryan in 1987, remembering department gatherings outside the Cellar of Old Union to disagree about literature or debate the politics of the Joseph McCarthy era.

He had a keen sense of humor and loved good food and wine, looking forward to his evening gin and tonic, as well as his morning ritual of breakfast and tea with Ruth as they read the New York Times aloud to each other.

Though Stone was diagnosed with congestive heart failure in late 2014, he remained lively and intellectually engaged, such that friends and family thought he’d somehow make it to 100. His loved ones were struck by his gift for being fully present while also happily planning for the future.

Stone was born Aug. 18, 1917, in Springfield, Massachusetts, to Clara Ella Gilbreth and Lester Lyman Stone. He is survived by his wife, Ruth Carleton of Stanford; his children, Dr. Gregory Stone of San Antonio, Texas, and Dr. Miriam Lee Stone of Seattle; Ruth’s children, Nancy Grimley Carleton of Berkeley and Jeff Grimley Carleton of Palo Alto; and five grandchildren.

A memorial service celebrating Stone’s life will he held Saturday, Aug. 1, at 2 p.m. at the First Congregational Church of Palo Alto. Donations may be made to the Southern Poverty Law Center or to the charity of the donor’s choice.

Christina Dong is an intern at Stanford News Service.