Stanford professor, leading Miltonist Martin Evans dies at 78

The Welsh scholar is remembered for being a powerful mentor as well as a revered scholar. He infused his students with “a durable sense of joy.”

Update: A memorial service for J. Martin Evans will be held on Friday, April 19, at 5 p.m. in the Bechtel Conference Center in Encina Hall.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to a memorial fund in J. Martin Evans’ name. Checks should be made out to Stanford University and a notation in the lower left of the check or in a brief note accompanying the check should say it is for the J. Martin Evans Memorial Pending Fund (JZBAE). Please mail check to Stanford University Gift Processing, P.O. Box 20466-0466, Stanford, CA 94309.

J. Martin Evans grew up in a world without privilege – a hardscrabble and war-torn corner of the United Kingdom. Yet he became one of the foremost Milton scholars of his generation. The Stanford professor of English died Feb. 11 in his home of congestive heart failure. He was 78.

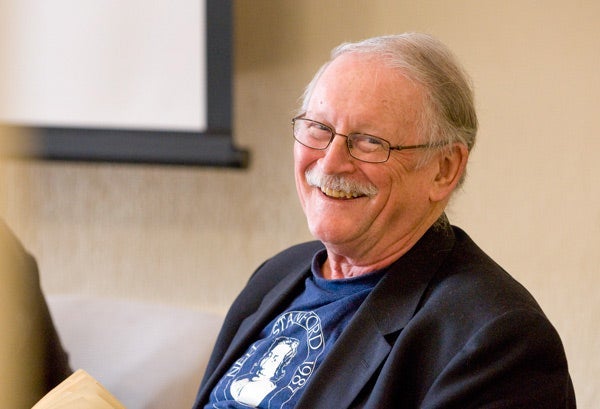

Martin Evans hosted a 400th birthday party for John Milton at Stanford in 2008, with a marathon reading of Paradise Lost. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Evans repeatedly maintained that John Milton was the most learned poet in the English language, and certainly Evans’ own influential books led many to see how profoundly the Puritan poet shaped Western culture. The Stanford scholar’s deeply learned teaching created decades of Milton scholars.

Evans put the stamp on his long career with his seminal ‘Paradise Lost’ and the Genesis Tradition (1968), a brilliant contribution to Milton scholarship that remains a landmark in the field.

Evans’ early triumph was followed by America, the View from Europe (1976), The Road from Horton: Looking Backward in ‘Lycidas’ (1983), Milton’s Imperial Epic: ‘Paradise Lost’ and the Discourse of Colonialism (1996) and The Miltonic Moment (1998.)

Evans coined the phrase “Miltonic moment” to describe the point of crisis just before the action changes dramatically, looking at once backward to a past that is about to be transcended or repudiated, and forward to a future that immediately begins to unfold.

His first reading of Milton marked a Miltonic moment of his own: “I fell hopelessly in love with the poetry. It was the most exciting thing I’d ever read,” Evans said.

Yet Evans is remembered for being a powerful mentor as well as a revered scholar.

The poet and scholar Linda Gregerson of the University of Michigan, his student in the late 1970s, recalled, “He was immensely generous, both personally and intellectually, able to convey deep learning with extraordinary clarity. He always took a deep delight in ideas, and was just opinionated enough to make things fun.” She recalled him as “impish, with a brilliant, irreverent sense of humor.”

“He converted many of us to a lifelong inhabitation in the world of Milton studies. It’s a formidable world in many respects, not nearly so genial as the world of Shakespeare studies, for example. But Martin imbued it, and us, with a durable sense of joy.”

According to English Professor Dennis Danielson of the University of British Columbia, editor of the Cambridge Companion to Milton, “He was wonderfully warm and brusque at the same time. He was a man of capacious mind, and not ashamed of his affections.”

Angelica Duran, director of religious studies and associate professor of English at Purdue University and editor of the Concise Companion to Milton, praised Evans for his powerful encouragement to her as a first-generation Chicana graduate student and single mother of two. “It made all the difference,” she said.

John Martin Evans was born in Cardiff, Wales, on Feb. 2, 1935, and always retained a bit of the Welshman about him. Christmas dinners were a chance to regale guests with his reading of choice, Dylan Thomas’ A Child’s Christmas in Wales. “It gives me a chance to renew my fast-disappearing Welsh accent,” he quipped in 1986.

Cardiff was a tough steelworking city that was targeted by the Germans – Evans’ boyhood school was destroyed by a bomb. Nevertheless, he was lucky always to find gifted teachers, one of whom became speaker of the House of Commons.

After a two-year stint working in military intelligence for the Royal Air Force from 1953 to 1955, Evans attended Oxford, where he received his BA in 1958 from Jesus College, and his MA and DPhil from Merton College in 1963. At Oxford, his thesis advisor was Dame Helen Gardner, the doyenne of 17th-century studies. Under her guidance, he began a lifelong career in Milton studies.

“He had superb training under an immensely distinguished mentor,” said Gregerson. “I think at times he must have been rather appalled at the relative laxness of training his American students brought to early modern studies, but if so, he never betrayed it. He always managed to convince us that our ideas were worth pursuing.”

Gardner was influential in other ways: She convinced Evans to apply to Stanford when the academic job market in Britain was so poor that 250 scholars with doctorates in English were competing for two university positions.

Duran recalled Evans telling her about his London interview for the job. He had to borrow a jacket, and didn’t know exactly where Stanford was. “It was the first time he tasted Beef Wellington. He said he fell in love with the good life,” she recalled.

Evans was offered the job, and immediately flew to Switzerland and proposed to Mariella Lafranchi, whom he had met at Oxford. He didn’t know half her family had emigrated to California decades before; Evans moved into a large extended family in the United States and never looked back.

In 2004, the Milton Society of America named him as a prestigious “honored scholar” for lifetime achievement (previous recipients include C. S. Lewis and Stanley Fish).

He hosted a 400th birthday party for John Milton in 2008, with a marathon reading of Paradise Lost – some called it a “Martinfest.” The event reunited many of his former students from across the United States and Canada.

At his death, he was in his 50th year of teaching at Stanford. He held many awards for his teaching and service, including the Bing Award for teaching (1992), the Richard W. Lyman Award (1990) and the Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching (1984). The 1987 Walter J. Gores Award for Excellence in Teaching cited “the magnificence of his teaching at all levels of the department curriculum” and “the passion about literature that infuses all his teaching and writing.”

Evans was associate dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences (1977-81), director of undergraduate studies (1983-86) and chair of the English Department (1988-91). He was named the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor in 2002.

He was a champion of the humanities, and passionate in their defense: “The humanist’s material is not a mysterious concatenation of natural phenomena or a mass of raw statistical data waiting to be given significance by the ordering mind of the analyst,” he wrote in a 2009 article in Stanford magazine.

“Our subject matter already has significance and order built into it. It already makes sense. Humanists are the servants of the works they study and teach, not their masters. They don’t expect to do something to their subject; they expect their subject to do something to them.”

He is survived by his wife of almost 50 years, Mariella Evans of Stanford; his daughter Jessica Evans, his son-in-law Yung Duong and grandson, Owen Evans-Duong, all of Oakland; and his daughter Joanna Evans and son-in-law David Harris of Ojai, Calif.

A memorial service is planned for the spring and will be announced at a future date. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made toward a memorial fund that will go to the Stanford English Department in his name.

Cynthia Haven is director of communications for the English Department and the Creative Writing Program.