Stanford’s acclaimed artist, Nathan Oliveira, dies at 81

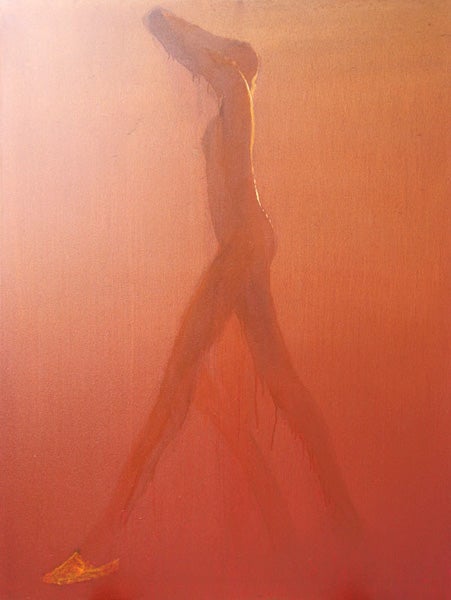

Oliveira described his art with the Portuguese word ‘saudade,’ a yearning and nostalgia. “I’m not part of the avant-garde,” he said. “I’m part of the garde that comes afterward, assimilates, consolidates, refines.”

Nathan Oliveira, the internationally acclaimed artist, died on Nov. 13 at his Stanford home from complications of pulmonary fibrosis and diabetes. He was 81.

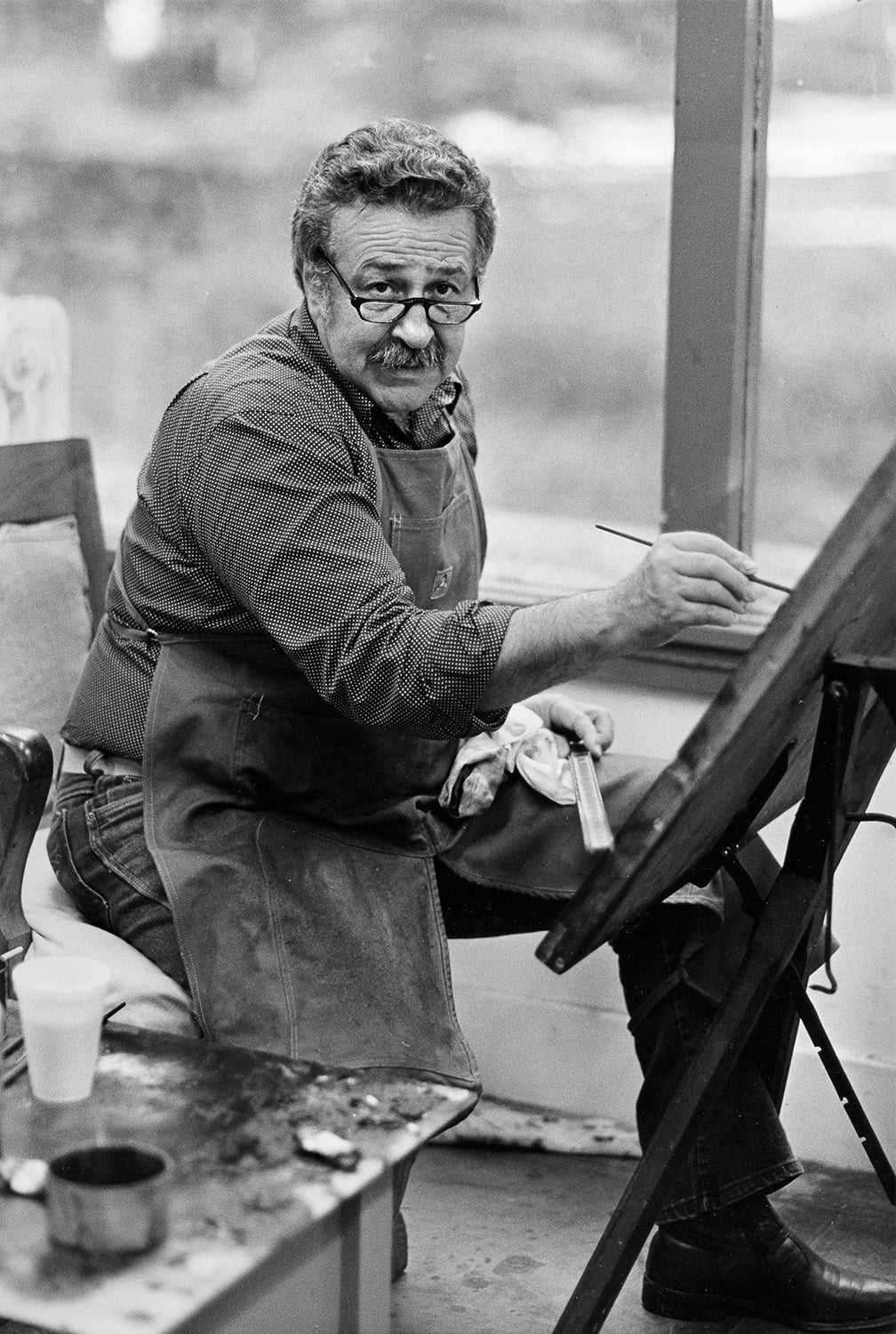

Nathan Oliveira joined the Stanford faculty in 1964. (Image credit: Chuck Painter / Stanford News Service)

Oliveira was a familiar sight among the foothills around Stanford’s Dish, looking for kestrels and red-tailed hawks with one of his Rottweilers by his side. But Windhover was only one facet of an illustrious career. “I always felt he was a painter of extreme talent and ingenuity, right to the end of his life,” said Peter Selz, the renowned art historian and author who curated an Oliveira retrospective in 2002, calling him “a brilliant, brilliant lithographer” and “the most original figurative painter of his time.”

According to Selz, Oliveira revived printmaking, which had gone into decline in the 1960s and 1970s. A superb printmaker, painter and sculptor, he was also one of the leaders in a movement half-a-century ago that rebelled against the dominant trend of abstraction.

“I’m not part of the avant-garde,” Oliveira told Stanford magazine in 2002, “I’m part of the garde that comes afterward, assimilates, consolidates, refines.”

Although he retired in 1995, Oliveira remained active until the end of his life, with 30 paintings in progress. He experienced “a tremendous explosion of creativity in the months before his death,” according to John Seed, a professor of art and art history at Mt. San Jacinto College in Southern California, writing in the Huffington Post.

“The outpouring was remarkable, since Nathan was suffering from pulmonary fibrosis and was tethered to an oxygen tank,” said Seed, who described his former Stanford mentor as “an exceptionally fine painter and an empathetic teacher. In his own art, and in the art that he admired, he was involved in the search for something that transcended time.”

‘A wonderful wicked sense of humor’

Mona Duggan, associate director of the Cantor Arts Center and a close friend for decades, described him as “genuine and warm, with a wonderful wicked sense of humor.”

“Obviously, as an internationally acclaimed artist, he brought great distinction to the Department of Art and the university. He was most well-known during the Bay Area Figurative movement – but his entire career was quite remarkable.”

Oliveira was born Dec. 19, 1928, in Oakland, the child of poor Portuguese immigrants. His father drowned in the Russian River when Oliveira was young; he lived with his mother and aunt in his grandmother’s apartment and struggled with dyslexia in school.

He took his first art lessons in high school from a painter who made seascapes for San Francisco tourists, but a chance visit to the Palace of the Legion of Honor changed his life’s direction. He encountered Rembrandt’s 1632 Joris de Caulerii and, face-to-face with the great work of art, he decided that he, too, wanted to paint people.

After George Washington High School in San Francisco, Oliveira began his college experience at Mills College, where he studied one summer with the German expressionist Max Beckmann, who disliked abstract painting, calling it “nail polish.”

Although he spoke little English, Beckmann was a compelling teacher and a connecting link to European painting traditions. Oliveira later said, “He seemed like a very fundamental man, whose only interest was in painting – that’s all he wanted to do. Still, I think from our encounters he communicated, indirectly, what artistic values were about.”

Oliveira earned his bachelor’s degree in fine arts in 1951 and his master’s in fine arts in 1952 at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland (later the California College of the Arts.) He married Ramona, the daughter of Cincinnati Reds baseball player Walter “Cuckoo” Christensen, in 1951, and began teaching at the Richmond Art Center, at San Francisco’s Art Institute and at his alma mater, for $2.50 an hour.

“When Mona and I got married and had children, we weren’t making very much money,” he said in the 2002 interview. “After we’d get the bills paid, I’d say to her, ‘Well, how many tubes of paint can I get this week – one of red, or two of yellow?'”

Oliveira became a leader in the Bay Area Figurative movement in the late 1950s – an informal movement that rebelled against the hegemony of abstract expressionism and reintroduced the human figure. In the group he met Stanford alumnus and modernist artist Richard Diebenkorn, who became a lifelong friend.

The late Lorenz Eitner recruited him to the Stanford faculty in 1964, after artist-in-residencies at Harvard, the University of California-Los Angeles, Cornell, Notre Dame, the University of Illinois and other institutions. He was already acquiring a national reputation as a cutting-edge artist.

Work exhibited around the world

He held exhibitions in New York, London, Melbourne, Paris and Stockholm. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art alone owns more than 30 examples of his work.

The Windhover project began four decades ago. “I have always related to this predatory bird, but mostly through ancient art,” he said in an interview for Cantor Arts Center in 1995.

A graduate teaching assistant gave him an actual stuffed kestrel: “Beginning in 1970 I painted about 75 small oils and drawings to bring the bird back to life.” Some of the monumental works measured up to 17 feet across.

In 1988, the art department gave him the use of a large new studio in the hills around Stanford, allowing him to work on several large canvases at once. Oliveira continued his distillation of light and flight – the wings of his birds often echoing the curvature of the planet.

When Irish poet laureate Desmond Egan visited Oliveira, his first words on entering the studio were “Windhover,” referring to Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem, The Windhover: To Christ Our Lord.

“He made this wonderful correlation, and my father was awestruck,” said Joe Oliveira, the artist’s son, agent and manager.

While he was actively teaching, “many chose to come to Stanford to study with him,” said Duggan, recalling a student who was not an arts major telling her that “his single most memorable experience at Stanford was taking a drawing class in Nathan’s studio. He was just as remarkable as a professor as he was an artist.”

John Seed told Stanford magazine: “Teaching, at its best, is about transforming the way students think, and Oliveira changed my thinking forever by introducing me to a process-oriented way of problem-solving. Monoprint is a printmaking method in which a quick painting is brushed, smudged and wiped onto a zinc plate, then pressed onto wet paper with an etching press. Although each image is unique, a faint ‘ghost’ image remains after each impression. Oliveira encouraged us to treat each such image as the starting point for another print.

“When he gave a slide show of his Tauromaquia monoprints, a seemingly endless series of themes and variations inspired by Goya, my jaw was dropped the whole time. Oliveira’s way of thinking was so stunningly flexible and inventive.”

Oliveira’s honors include an award by the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters and election to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. He was named as the first holder of the Ann O’Day Maples Professorship in the Arts in 1988. But some say he was proudest of receiving the Commander of the Order of Henry the Navigator from the president of Portugal, for those who have expanded Portuguese culture and history, awarded in 1999.

Selz said that Oliveira described his artwork with the Portuguese word saudade, a feeling of yearning and nostalgia. In general, however, he seemed reluctant to describe or categorize himself. “I am a painter. That is what interested me initially as a young person and this attraction has continued throughout my lifetime,” he said in a Cantor interview. “I have never tried to alter the art world in any way. I simply wanted to become part of it. Success in what I do is measured by surviving into one’s mature years and continuing to find enough genuine reasons to work.”

His wife, Ramona (Mona), died in 2006 of cancer. He is survived by his sister, Marcia Heath of Milbrae; his three children, Lisa Lamoure of Fresno; Gina Oliveira of Kihea, Maui; and Joe Oliveira of Palo Alto; and five grandchildren.

A memorial is planned for the afternoon of Jan. 12, 2011, at Stanford Memorial Church, at a time to be announced later.