Stanford English Professor Emeritus Thomas C. Moser, psychological biographer of Joseph Conrad, dies at 92

Moser, a Stanford scholar celebrated for his penetrating biographies of Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford, spearheaded Stanford’s Department of English during the upheavals of the mid-1960s.

Thomas C. Moser, an emeritus professor and former chair of the Department of English at Stanford University, died June 9 of complications from pneumonia at his home on Stanford’s campus. He was 92.

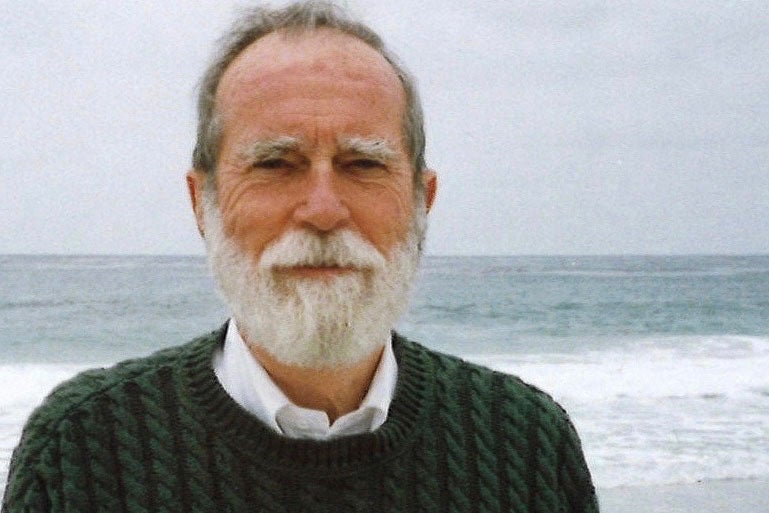

Thomas C. Moser (Image credit: Courtesy of the Moser Family)

A beloved colleague, teacher and scholar, Moser arrived at Stanford in 1956 and chaired the Department of English between 1963 and 1968, a period of social tumult not only on campus but around the world. Embracing the spirit of the times, he revamped the department, hiring women as faculty members and advocating for Stanford to establish its first global campuses in Europe. Moser’s openness extended to his home, where he often held seminars and invited lonely undergraduates to Thanksgiving dinner.

As fellow Professor Emeritus of English Albert Gelpi said of Moser, “All who knew him came to trust and rely on his unfailing loyalty and honesty, his deeply caring heart, his compassionate understanding.”

Longtime friend and colleague Professor Emerita of English Barbara Gelpi observed that Moser could recall minutiae from works of literature and history with the same ease he conjured up memories of “his Pennsylvania boyhood, his friendships, his family life, his years at Harvard, Wellesley, and then at Stanford.”

“It doesn’t seem an overstatement to say that Tom made my professional life possible,” Gelpi said of her trajectory from part-time lecturer to professor. She and her husband, Albert, came to Stanford in 1968, near the end of Moser’s time as department chair. Seeking to advance the couple’s careers, he offered Gelpi “a chance to function in the profession that married women, and especially women with children, very rarely received at the time.”

“Tom was an extraordinarily generous man,” said Elizabeth Traugott, a lecturer at the time Moser was chair. “He was a mentor to me as a woman in academia when there were only a few of us.” After becoming a full professor, Traugott would chair Stanford’s Linguistics Department and serve as vice provost and dean of graduate studies in the late 1980s.

Psychological biography as literary criticism

Matching Moser’s enthusiasm as a teacher and mentor was his perspicuity as a scholar. An expert on Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford, luminaries of early 20th century British literature, his publications blend literary criticism and psychological biography, yielding fresh scholarship that garnered him fellowships from the American Council of Learned Societies in 1963 and the Guggenheim Foundation in 1979.

The first of these studies was Joseph Conrad: Achievement and Decline (1957). Plumbing Conrad’s writerly psyche, Moser detects signs of the author’s eventual “decline” as his literary output peaked – roughly, from 1898 to 1911, when he depicted moral failings in masterpieces like Heart of Darkness (1899) and Lord Jim (1900) before delving into the less successful political novels of his later career.

Among Conrad scholars, Moser was the first to ask when the author reached his peak and when, if at all, he fell into a slump. Peter L. Mallios, an associate professor of English at the University of Maryland and author of Our Conrad: Constituting American Modernity (2010), considers Moser’s question of decline “the most significant, long-lived and contested argument in Conrad studies, and one that will never die.”

Scholars belonging to the Joseph Conrad Society of America would wholeheartedly agree, having awarded Moser the Ian P. Watt Award – its highest distinction, named after another Stanford-based Conrad scholar – in 2002. Conradiana, the U.S.-based Conrad journal, has announced a forthcoming special issue to honor his memory.

Moser also carved out a name for himself among Ford scholars. Two decades of research culminated in his publishing The Life in the Fiction of Ford Madox Ford (1980), in which he details the conditions of Ford’s life that led him to compose The Good Soldier (1915), his magnum opus, departing from the tenor of his previous works. According to Moser, Ford’s life experiences manifest in plots, characters and relationships, with each book being a snapshot of the author’s state of mind.

For Mallios, this literary encounter, deeply rooted in personal and cultural history, reflects “a dignity in how Tom goes about reading and rendering literature that is as distinctive as it is infectious.” Indeed, life and literature came together for Moser when he spent long stretches of time with Ford’s family in England as part of his research for the biography. Over time they became friends, and the family even paid him a visit at Stanford.

Moser’s other publications include scholarly editions of Conrad’s Lord Jim, Ford’s The Good Soldier and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847).

Early life and route to the Farm

Moser was born in Connersville, Pennsylvania, the only child of Oliver Perry Moser and Anna Mary Holborn. The family moved to Pittsburgh during the Great Depression, where his father worked as a clerk for the B&O Railroad. After graduating from Dormont High School, Moser studied engineering for a year at the University of Pittsburgh before being drafted into the army, where he performed a three-year tour of duty as an electrical engineer in the European and Pacific theaters.

Upon returning from the war, Moser received support from the G.I. bill to attend Harvard University, where he earned his A.B. in English in 1948 and a Ph.D. in the same discipline in 1955. In 1952, while pursuing doctoral study, he married Mary Churchill Small, a dean at Radcliffe College (now part of Harvard University). Doctorate in hand, Moser taught for a brief time at Wellesley College before accepting a position at Stanford in 1956. He served as director of freshman English from 1959 to 1962 before chairing the department.

In 1986, following Mary’s death, Moser married Joyce Penn, a civil law attorney, scholar of American literature and teacher in Stanford’s Department of English and Writing Program, who also works as an administrator in the Introductory Studies Program. He retired in 1992 and retained emeritus status for the rest of his life.

Moser is survived by Joyce, his wife of 30 years; a son from his first marriage, Thomas C. Moser Jr., of Ellicott City, Maryland; a daughter from his first marriage, Fredrika Churchill Moser, of Garrett Park, Maryland; and three grandchildren, Lucy Murnane, Polly Moser and Toby Moser.

A memorial service will be held in the fall, with details to follow.