Sea Trek: Stanford researcher’s childhood dreams of space bend toward the ocean deep

A keen interest in the possibility of alien life ultimately led geomicrobiologist Anne Dekas to study some of the least-examined microbes on Earth – those dwelling in the deep sea.

It’s a long, cramped journey through pitch blackness. Inside a thick-hulled submersible, Anne Dekas and two colleagues are squeezed into a space barely bigger than a car’s front seat. After the first 200 meters, sunlight can penetrate the ocean no further, though the flashes of bioluminescent sea creatures provide a welcome respite in the inky abyss.

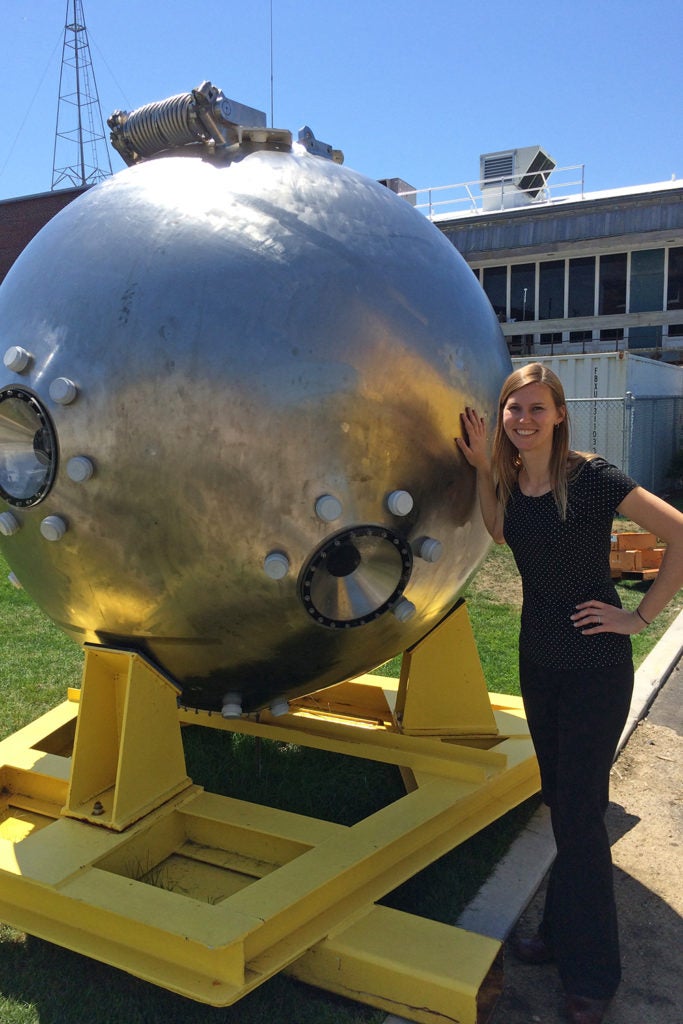

Dekas with Alvin’s sphere in 2016 – the part researchers actually go inside – without the housing after it was replaced during the last renovation. (Image credit: Amy Wagner)

An hour-long descent culminates with touchdown upon the ocean floor, where few humans have ever gone. At last, the lights of the submersible, dubbed Alvin, silently switch on, illuminating an alien landscape. “You see this barren landscape extending in front of you, and you really do feel like you’re on another planet,” said Dekas, an assistant professor of Earth system science at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth).

Dekas’ younger self would have appreciated that moment. As a child, she had yearned to visit other planets and search for alien life. As Dekas went on to college, her interests ultimately bent away from journeying into space and instead into another expanse, in many ways just as remote: the bottom of the ocean.

Instead of an astronaut, she became more like an aquanaut.

“Wondering about astronomy and the origin of life is really what got me into marine biology, because I realized there was this unexplored frontier right here on Earth,” Dekas said.

Still to this day, the surface of the Moon remains better characterized than the Earth’s deep ocean floor. A vast, submerged landscape that spans nearly three-quarters of our planet’s surface, it’s a forbiddingly inaccessible realm, miles deep, pitch black and crushed under hundreds of times the atmospheric pressure felt on land.

As an assistant professor at Stanford, Dekas has focused her research on the hardy microbes that manage to thrive in deep ocean waters and sediments. These creatures are some of the least-studied organisms in existence. Dekas and her colleagues have discovered that the deeper into the sediment you go, the more novel the microbial life becomes.

“A huge percentage of the cells are so diverged from what’s been previously described that we don’t even have a name for what they are,” Dekas said. In essence, these suboceanic microbes are her childhood’s dream come true: life that is as quasi-extraterrestrial as anything discovered to date.

Dekas’ specialty is geomicrobiology, which involves assessing the chemical changes microbes induce in the environment as a result of their nutrient metabolism. In other words, she is figuring out what elements the microbes ingest or take in and what they put back out as they go about their daily lives. For example, the microbes must capture the biologically critical element nitrogen. They also give off carbon dioxide and other so-called greenhouse gases that, once in the atmosphere, trap heat and warm the planet. In this way, the overall effects of the microbes’ induced environmental changes extend beyond just localized patches of ocean sediment. Cumulatively, deep-sea microbes represent a tremendously large, last layer of life, whose overall influence on the planet remains poorly understood.

“Because they occupy such an expansive space, and because for so many years they were nearly completely ignored, there’s a lot to learn about the part these microbes play in Earth’s global biogeochemistry and climate,” Dekas said.

The shelves of the refrigerators in her lab at Stanford are lined with bottles of deep-sea mud and water where the peculiar microbes live. One major research activity involves extracting DNA from the microbes to learn about them on a fundamental biological level. Dekas and her team also run experiments, altering water and nutrient conditions to gauge how the critters react.

In 2009, during her first dive as a graduate student, Anne Dekas collects methane-seep sediments from the deep-sea submersible Alvin. (Image credit: Victoria Orphan, Caltech)

In order to get their hands on the rarefied microbes in the first place, Dekas and her collaborators must go right to the source. It’s one of her favorite aspects of the profession, going on expeditions out into the Pacific Ocean to gather samples. “Being out on the ships in the ocean, looking at the world we’re trying to understand, that’s the most exciting part,” Dekas said.

One method her team employs involves sinking a piece of tethered collection equipment off the side of a boat until it hits paydirt, captures a chunk of sediment, then is hoisted back up. A more precise method is sending down robotic submersibles – remotely operated submarines – that relay a video feed of the ocean floor to scientists on the boat, who then instruct the robo-sub to grab material near seafloor geological features of interest.

The most exciting way by far, though, is when Dekas gets to plumb the depths herself in a crewed submersible. “Getting to go to the bottom of the ocean is the cherry on top,” Dekas said. “It’s an incredibly moving experience that you really don’t have any other way in life.” Three times, she has traveled down to the ocean floor aboard Alvin, arguably the most famous submersible of all time and now nearly 60 years old. In the late 1970s, Alvin brought researchers face-to-face with then-newly discovered deep-sea hydrothermal vents; after that, to the long-sought wreck of the Titanic, found nearly 2.5 miles deep off the coast of Newfoundland in the mid-1980s.

Bit by bit, sample by sample, Dekas hopes to continue gaining a fuller view of the limits of biology on Earth and how life is inextricably connected to its non-living environment. Along the way, these research pursuits have helped Dekas gain a fuller view of herself as well, and why she once found astronautics so appealing.

“Over time, I came to realize that what was so inspiring to me about being an astronaut was not specifically going into space,” said Dekas. “It was much more about discovery, exploring the unexplored and the unknown and contributing to human civilization in a way that transcends my lifetime – with knowledge. Once that crystalized for me, I realized scientific research was how I wanted to spend my life.”

Stanford Report is exploring the stories behind the curiosity and excitement that drives foundational discoveries in the arts, humanities, social sciences and sciences.