For decades, Stanford University has been inventing the future of robotics. Back in the 1960s, that future began with an Earth-bound moon rover and one of the first artificially intelligent robots, the humbly christened Shakey. At that time, many people envisioned robots as the next generation of household helpers, loading the dishwasher and mixing martinis. From those early ambitions, though, most robots moved out of the home and to the factory floor, their abilities limited by available technology and their structures too heavy and dangerous to mingle with people.

But research into softer, gentler and smarter robots continued.

Thanks in large part to advances in computing power, robotics research these days is thriving. At Stanford alone, robots scale walls, flutter like birds, wind and swim through the depths of the earth and ocean, and hang out with astronauts in space. And, with all due respect to their ancestors, they’re a lot less shaky than they used to be.

Here we look at Stanford’s robotic legacy – the robots, the faculty who make them and the students who will bring about the future of robotics.

The Stanford Cart

Up in the foothills above campus in the late ’70s, a CAUTION ROBOT VEHICLE sign alerted visitors to keep an eye out for the bicycle-wheeled Stanford Cart, which could sometimes be seen rolling along the road. The Stanford Cart was a long-term project that took many forms from around 1960 to 1980. It was originally designed to test what it would be like to control a lunar rover from Earth and was eventually reconfigured as an autonomous vehicle.

(Image credit: The Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University)

Shakey

Named for its wobbly structure, Shakey was the first mobile robot that could perceive its surroundings and reason about its actions. Work on Shakey began in 1966, at the Stanford Research Institute’s Artificial Intelligence Center in Menlo Park. Shakey led to advances in artificial intelligence, computer vision, natural language processing, object manipulation and pathfinding.

(Image credit: © Mark Richards; courtesy of the Computer History Museum)

Stanford Arm

Known as the Stanford Arm, this robotic arm was developed in 1969 and is now on display inside the Gates Building on Stanford campus. It was one of two that were mounted to a table where researchers and students used it for research and teaching purposes for over 20 years, often focused on applications in the manufacturing industry. In 1974, a version of the Stanford Arm was able to assemble a Ford Model T water pump. It was the precursor of many manufacturing robots still in use today.

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Mobi

In the main hall of the Gates Building at Stanford, a three-wheeled, human-sized robot stands sentry by the door. It’s known as Mobi and researchers developed it in the ‘80s to study how autonomous robots could move through unstructured, human-made environments. Mobi was a testbed for several kinds of sensors and navigated with stereo vision, ultrasound and bump sensors.

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

STAIR

Pushing back against the trend of artificially intelligent robots designed for specific tasks, the Stanford AI Robot – STAIR – was going to be multi-talented, navigating through home and office environments, cleaning up, assembling new furniture or giving visitors a tour, à la the Jetson’s Rosie.

Although STAIR came along 40 years later, the robot was very much created in the tradition of Shakey.

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Autonomous helicopters

Aiming to improve the capabilities of autonomous helicopters, Stanford researchers decided to build on the skills of expert human operators. The researchers developed an algorithm – called an apprenticeship learning algorithm – that enabled the autonomous helicopters to learn to fly by observing human operators flying other helicopters. The helicopters were then able to perform spectacular acrobatic feats and the project went so well, that the researchers decided there was no further work left to do on that topic.

(Image credit: Ben Tse)

Stickybot

The lizard-like Stickybot could scale smooth surfaces thanks to adhesive pads on its feet that mimic the sticking powers of a gecko’s toes. A robot like this could serve many purposes, including applications in search and rescue or surveillance.

Since their invention, gecko adhesives have helped drones, people and robots in space grab hold of otherwise hard to grasp surfaces.

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Hedgehog

A toaster-sized cube with knobby corners may someday help us explore asteroids, comets and small moons. Dubbed Hedgehog, this tiny explorer turns the challenges of operating in low-gravity environments into an advantage. In places where there’s not enough gravity for wheeled vehicles to gain traction, Hedgehog moves in hops and flips – absorbing shocks with its bulbous corners. In June 2015, Hedgehog was tested on a parabolic flight to simulate microgravity and performed well. Next, the researchers are figuring out how to make their robot navigate autonomously.

(Image credit: Ben Hockman)

OceanOne

Shaped like a mermaid, OceanOne is a humainoid robotic diver that can be controlled by humans from the safety of dry land. The OceanOne team has already sent their robot to the briny deep to retrieve artifacts from a shipwreck and explore a volcano.

OceanOne’s operators can precisely control the robot’s grasping through haptic feedback, which lets them feel physical attributes of objects the robot touches with its hands. OceanOne and robots like it may someday take over dangerous and treacherous tasks for humans, including ship repair and underwater mining.

(Image credit: Frederic Osada and Teddy Seguin/DRASSM)

Flapping robots

When it comes to the art of flying, nature has many tricks and techniques we’d like to borrow. Examples of this include how to better hover, fly in turbulence and stay aloft on wings that change shape. Studying the wings of bats and birds, researchers at Stanford created flapping robots with wings that morphed passively, meaning no one controlled how they changed shape. To further their work on flapping flight, this lab has also built bird wind tunnel, studied vision stabilization in swans and put safety goggles on a bird named Obi – so they could measure its flight in subtle detail using laser light.

Recently, the researchers have taken their work into the wider world, reconstructing sensitive force-measuring equipment in the jungle to see how wild hummingbirds and bats hover in Costa Rica.

(Image credit: Courtesy Lentink Lab)

Vinebot

It resembles step 1 of a balloon animal but the Vinebot is an example of soft robotics. As the nickname implies, Vinebot’s mode of movement was inspired by vines that grow just from the end.

The advantage of this method of travel is that Vinebot can reach destinations without moving the bulk of its body. Because it never needs to pick itself up or drag its body, Vinebot can grow through glue and over sharp objects without getting stuck or punctured.

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

JackRabbot

Named for the jackrabbits often seen on campus, the round, waist-height social robot JackRabbot 2 roams around Stanford, learning how to be a responsible pedestrian. JackRabbot 2’s street smarts will come from an algorithm, which the researchers are training with pedestrian data from videos, computer simulations and manually controlled tests of the robot. These data cover many unspoken rules of human walking etiquette, such as how to move through a crowd and how to let people nearby know where you’re headed next.

JackRabbot 2 can also show its intentions with sounds, arm movements or facial expression. Researchers are hoping to soon test JackRabbot 2’s autonomous navigation by having it deliver small items on campus.

(Image credit: Amanda Law)

David Lentink

“I have largely avoided following trends because so many of them are focused on short-term advances. Also, by defining our own area of research we can focus more on collaborating with other labs instead of competing.”

In Lentink’s Q&A he describes his lifelong interest in flying machines and why he avoids following research trends in his field.

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

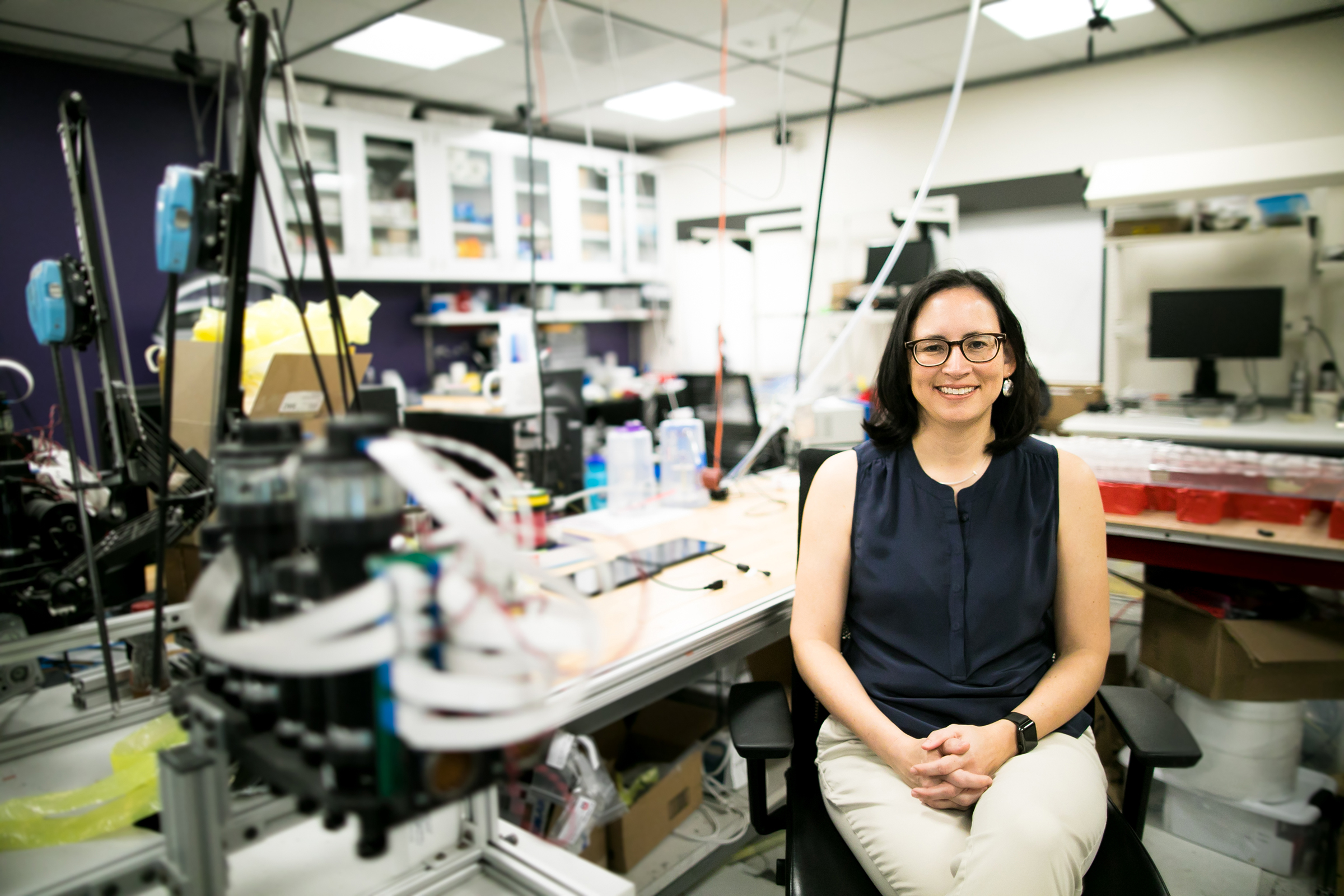

Allison Okamura

“When I was a graduate student, I definitely thought that this problem of robots being able to manipulate with their hands would be solved. I thought that a robot would be able to pick up and manipulate an object, it would be able to write gracefully with a pen, and it would be able to juggle.”

In her Q&A, Okamura discusses her first robotics project and the resurgence of creativity in robotics she’s witnessing – and influencing.

Image credit: Holly Hernandez

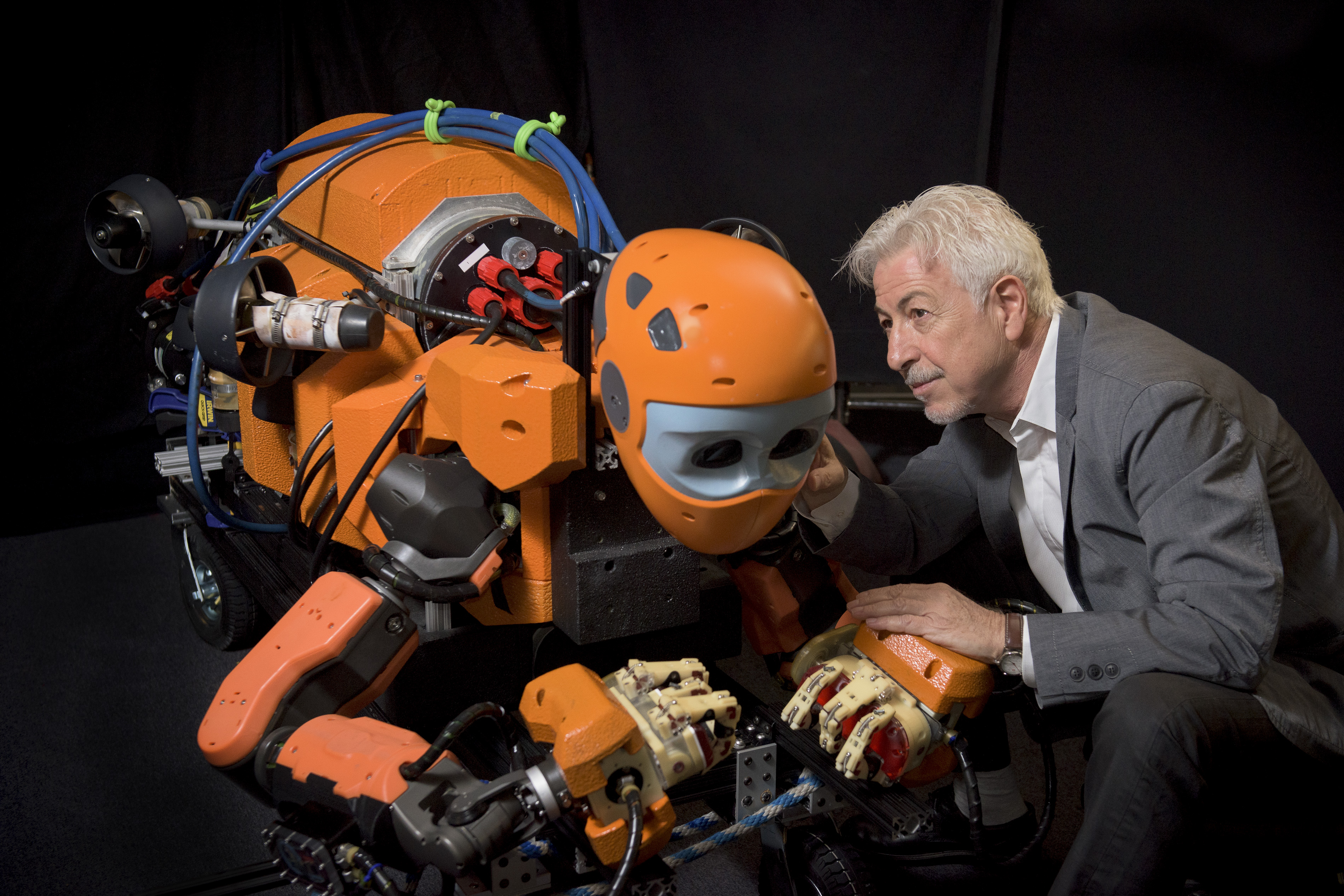

Oussama Khatib

“It took years for technologies to develop, and it is only now that we are certain that we have what it takes to deliver on those promises of decades ago – we are ready to let robots escape from their cages and move into our human environment.”

Khatib discusses a fateful bus ride that brought him to Stanford and the thesis project he’s never left behind in this Q&A.

Image credit: L.A. Cicero

Mark Cutkosky

“It’s clear that robotics has grown enormously. There is huge interest from our students. Many new applications seem to be within reach that looked like science fiction a couple of decades ago.”

In his Q&A, Cutkosky describes how his research turned from robots in manufacturing to robots that can climb walls.

Image credit: Rod Searcey

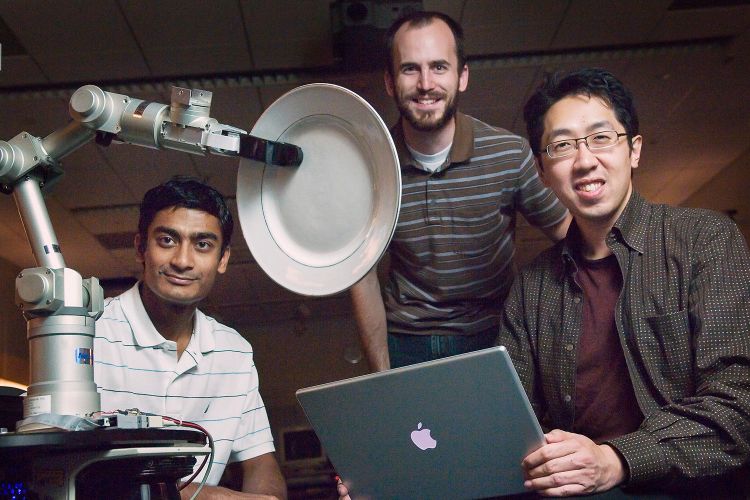

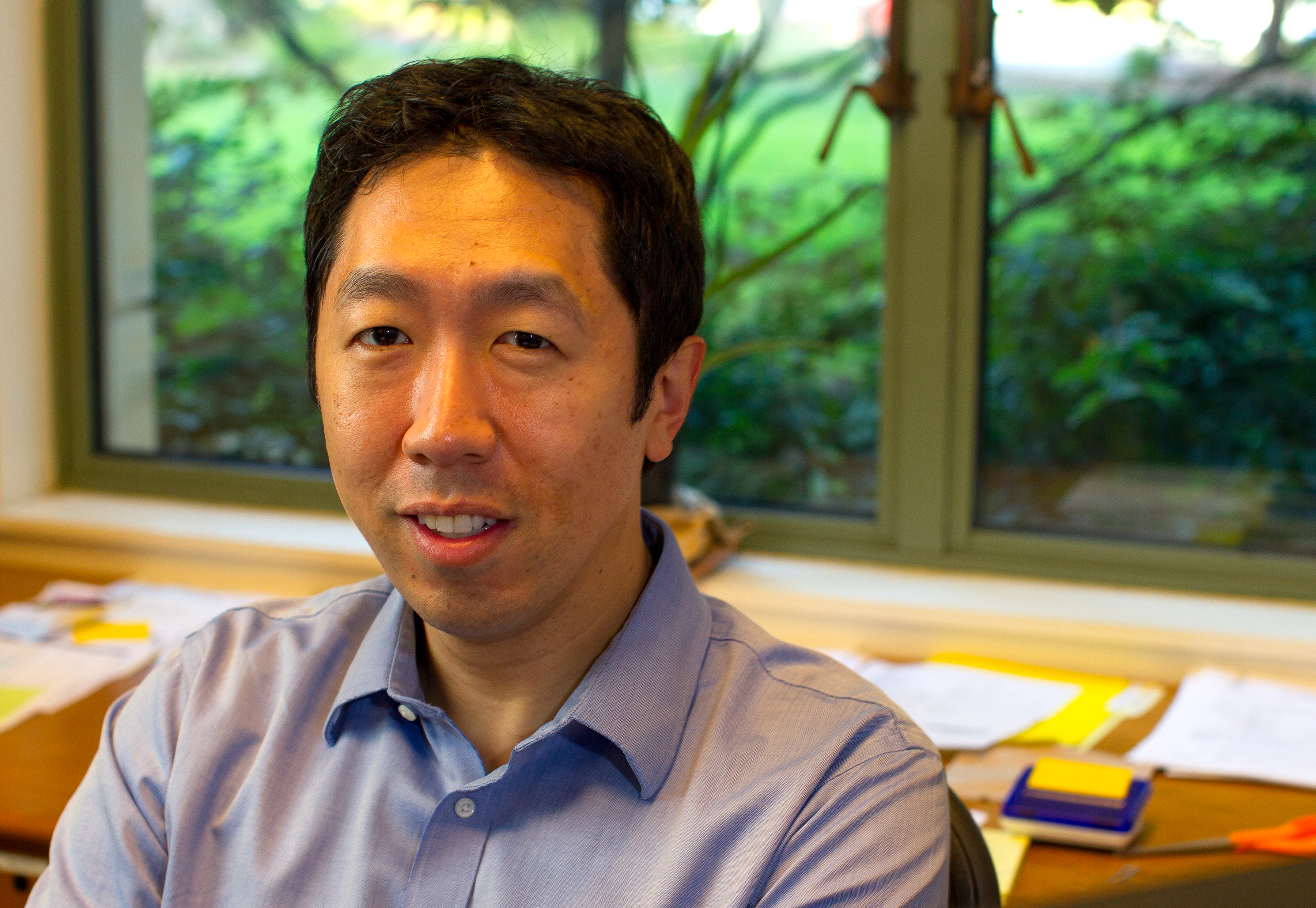

Andrew Ng

“When I was in high school, I did an internship […] and I did lot of photocopying. I remember thinking that if only I could automate all of the photocopying I was doing, maybe I could spend my time doing something else. That was one source of motivation for me to figure out how to automate a lot of the more repetitive tasks.”

Ng describes how he went from robots that play chess to developing robotics technology that traveled to the International Space Station in this Q&A.

Image credit: Norbert von der Groeben