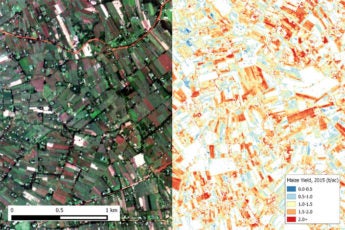

California Gov. Jerry Brown closed out his landmark Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco on Sept. 14 with a declaration that in order to monitor pollutants that cause climate change, California will go into orbit.

“With science still under attack and the climate threat growing, we’re launching our own damn satellite,” Brown said in prepared remarks. “This groundbreaking initiative will help governments, businesses and landowners pinpoint – and stop – destructive emissions with unprecedented precision, on a scale that’s never been done before.”

Brown’s statement echoes an understanding among scientists – including many at Stanford – that remote sensing data can and has revolutionized knowledge of Earth.