The First Transcontinental Railroad of the United States, constructed between 1863 and 1869, was arguably one of the most ambitious American engineering enterprises at the time and the source of much of the wealth used to create Stanford University. Reducing the time it took to cross the continent from months to days, the railroad helped pave the way for Western migration.

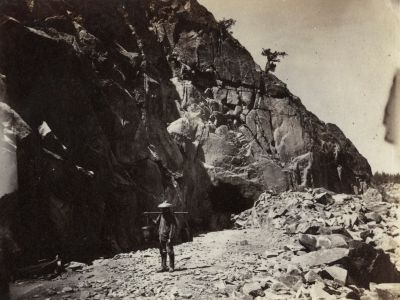

Often left out of the storytelling about the effort is the labor of an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 Chinese migrants who laid the tracks of the western half of the railroad. Those workers pounded on solid rock from sunrise to sunset, hung off steep mountain cliffs in woven reed baskets and withstood the harshest winters on record in the Sierra Nevada.

They were paid less than white workers, and hundreds lost their lives as a result of the dangerous work, said Gordon Chang, professor of American history at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences.

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

Image credit: Alfred A. Hart Photographs, 1862-1869, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries

While scholars have long recognized that Chinese migrants were crucial to the railroad’s construction, the details of those workers’ lives remained largely unknown until a team of Stanford scholars created the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project in 2012 to recover their history.

“Without the Chinese migrants, the Transcontinental Railroad would not have been possible,” said Chang, who is the Olive H. Palmer Professor in the Humanities. “If it weren’t for their work, Leland Stanford could have been at best a footnote in history, and Stanford University may not even exist.”

The project is co-directed by Chang and English Professor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, who is the Joseph S. Atha Professor in Humanities and director of the American Studies Program.

Over the past seven years, the project’s researchers undertook the most exhaustive search ever conducted for materials related to the Chinese railroad workers. The team’s findings are being published in two forthcoming books: The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad, which Fishkin and Chang edited, and Chang’s Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad.

The project’s team is hosting a public event at 2 p.m. Thursday, April 11, at Tresidder Oak Lounge to share its findings, as well as historical photographs, oral histories, lesson plans, artifacts and other materials gathered as part of the research. The event is part of a series of commemorations sponsored by departments throughout campus to mark the 150th anniversary of the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad.

Tracing the Chinese migration

Stanford research has revealed that most of the Chinese railroad workers were young, single men who came from the Pearl River Delta region of southern China’s Guangdong province. The area, which is near Hong Kong, was the front line of the two Opium Wars that England fought with China and was further disrupted by ethnic fighting.

As a result, more than 2.5 million Chinese left their country during the 19th century for other places throughout the world, including the United States, said Barbara Voss, an associate professor of anthropology who helped coordinate the work of archaeologists as part of the project.

“Out-migration was a strategy that a lot of families in that region used as a means of survival,” Voss said.

The Central Pacific Railroad, which was tasked with constructing the western half of the Transcontinental Railroad, began hiring Chinese workers in 1864 after facing a labor shortage that jeopardized the railroad’s completion. The Chinese eventually made up 90 percent of the workforce that laid the 690 miles of track between Sacramento, California, and Promontory, Utah.

Contrary to what was previously believed, many of the Chinese workers were literate, at least on a basic level, Fishkin said, citing new historical evidence uncovered by the project. They were also well organized. About 3,000 went on strike in 1867 to demand the same wages as the white workers, who were paid more than twice as much. The work was dangerous, often involving the placement of explosives used to clear a path through the granite Sierra Nevada. As many as 1,000 workers, perhaps more, are believed to have died from accidental explosions or the frequent snow or rock avalanches, according to the researchers.

Reconstructing workers’ experiences

Telling the full story of the Chinese workers has been difficult. No letter or other text written by one of the railroad workers has ever been found in China or in the United States. The absence of documents from the workers can be explained by several factors, including the devastation of their home villages in China due to social conflict and war and the obliteration of 19th-century Chinese communities in the U.S. through arson, looting and violence, the researchers said.

“The interesting question is: How does one recover a story of a past, lived experience when there is nothing from the subjects themselves?” Chang said. “We had to be very creative in our approach, using journalism, archaeology, memoirs of other Chinese and the railroad’s business reports to reconstruct what happened.”

Chang, Fishkin and other members of the project collected and analyzed photographs, cemetery records and thousands of digitized 19th-century news articles that covered the construction of the railroad. They also examined payroll reports and correspondence from Leland Stanford and others of the “Big Four” in charge of building the Central Pacific Railroad.

More than 100 scholars from North America and Asia, from disciplines including history, American studies, literature, archaeology, anthropology and architecture, worked with Fishkin and Chang to aggregate and examine those materials.

In partnership with the Chinese Historical Society of America, the project’s team also interviewed almost 50 descendants of the Chinese who built the railroad.

“This project is a pioneering example of transnational, interdisciplinary collaboration,” Fishkin said, adding that the project’s team worked with about 20 scholars in Asia. “It’s rare for researchers to have this type of team effort on such a large scale.”

In fact, more than 100 archaeologists combined their efforts and findings as part of the affiliated archaeology network led by Voss. Pieces of Chinese ceramic bowls, work tools and other items have been discovered through different investigations of campsites along the Transcontinental Railroad. The evidence shows that Chinese workers had a variety of experiences. While some lived in large, permanent work camps for years at a time, others lived a nomadic lifestyle, moving to a new campsite every few days.

Analysis of the research and many of the materials scholars collected over the years will soon be available on the project’s website. A curated online Stanford Libraries exhibition showcases payroll records, photos of objects found through archaeological excavations and transcripts of oral history interviews with descendants.

“There has been inattention to the role of Chinese workers in this part of American history and our goal has been to correct that,” Chang said. “The process of making sense of history is never over. This project shows how the gathering of new research, the creative use of a variety of historical materials, but also changing opinion, makes a big difference in how we can understand the past.”