A compound with the unpresuming designation of EBC-46 has made a splash in recent years for its cancer-fighting prowess. Now a new study led by Stanford researchers has revealed that EBC-46 also shows immense potential for eradicating human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections.

Compared to similar-acting agents, EBC-46 excels at activating dormant cells where HIV is hiding, the study found. These “kicked” cells can then be targeted (“killed”) by immunotherapies to fully clear the insidious virus from the body. By pursuing this “kick and kill” strategy with EBC-46, researchers think achieving permanent elimination of HIV in patients – in other words, a cure – is possible.

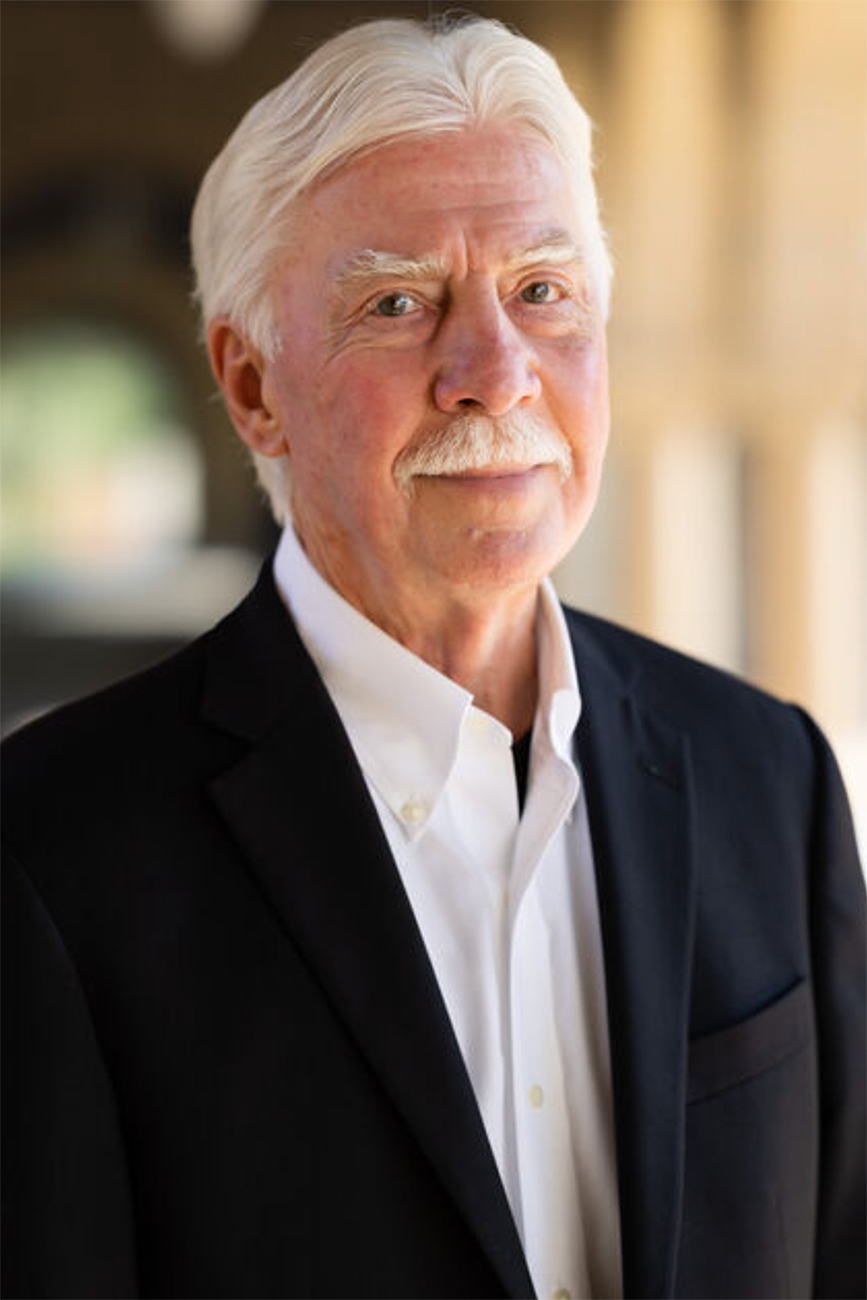

“We’re pleased to report that EBC-46 performed extremely well in preclinical experiments as part of a ‘kick and kill’ therapeutic,” said study senior author Paul Wender, the Bergstrom Professor of Chemistry at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences. “While we still have a lot of work to do before treatments based on EBC-46 might reach the clinic, this study marks unprecedented progress toward the as-yet-unrealized goal of eradicating HIV.”

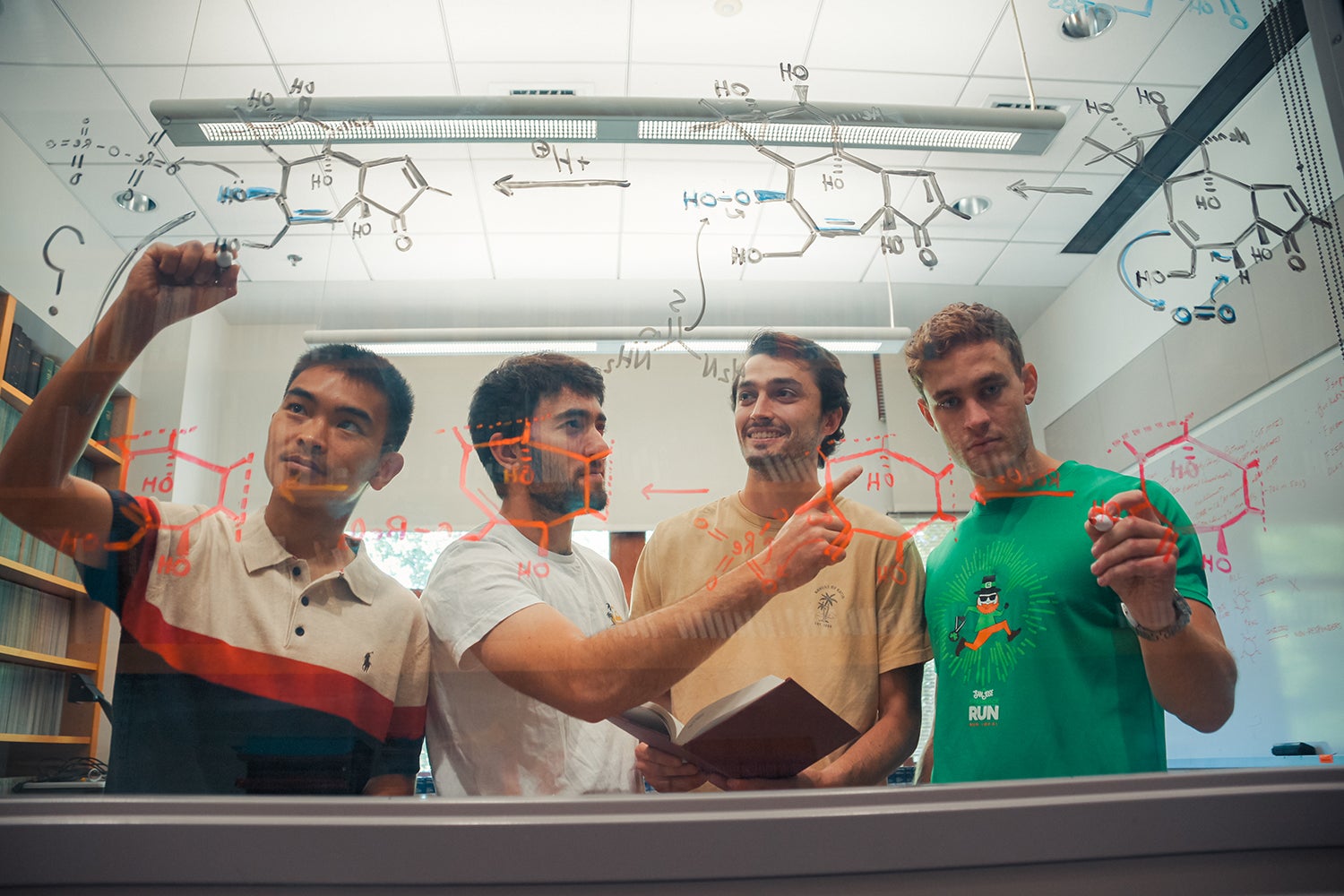

Stanford-affiliated co-authors of the study, published Jan. 24 in Science Advances, are Zachary Gentry, a postdoctoral student at Vanderbilt University and former Stanford doctoral student; Owen McAteer, a doctoral student in Wender’s lab; and Jennifer Hamad, an undergraduate biology student. These authors worked closely with collaborators at the University of California, Irvine (UCI) and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Paul Wender. | Do Pham

Tackling a generation-spanning epidemic

Technically known as tigilanol tiglate, EBC-46 was discovered a decade ago through automated drug screening by QBiotics, an Australian life sciences company. The compound naturally occurs in a single rainforest species, the blushwood tree (Fontainea picrosperma), found only in Australia’s tropical northeast. On a nitty-gritty biological level, EBC-46 binds to a key enzyme known as protein kinase C, or PKC. Numerous cellular processes rely on PKC, and many are involved with major diseases including AIDS (the advanced stage of HIV infection), cancer, and Alzheimer’s. Wender and colleagues have been exploring EBC-46 across these varied medical contexts.

In the case of HIV, the need for effective virus eradication strategies is paramount, Wender said. Since the virus emerged in humans more than 40 years ago, nearly 90 million people have been infected, and about half that many have died, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Around 40 million people are currently living with HIV, and, alarmingly, close to two million people become infected every year.

The rise of highly effective antiretroviral therapies (ARTs) has made the once-lethal infection into more of a chronic, manageable condition. But ARTs come with drawbacks of high cost, low access, and lifetime adherence.

“Part of the solution to the global HIV problem is addressing the 40 million people who are HIV positive,” said Wender. “Easing the medication burden and economic losses posed by the current HIV regimen, especially in developing countries, is critical.”

Flushing HIV out into the open

For the new study, the researchers set out to examine EBC-46’s value as a “latency reversing agent.” These agents kickstart certain pathways in latent cells infected by the virus. Latent cells act as a redoubt for HIV in the face of host immune attacks and medical treatments such as ART. Ferreting out these cells to expose them to treatment is thus essential for elimination of the virus in an infected person.

The Stanford researchers and their collaborators exposed latent HIV-infected cells to 15 analogs of EBC-46. Analogs are compounds that are chemically similar to the tree-derived compound and might be even more adept at kicking latent cells into gear. Prior work by Wender and colleagues made this wide-ranging EBC-46 research possible by resolving the issue of availability, given that the compound’s only natural source is a regional Australian tree. In a 2022 study, Wender and colleagues debuted a novel way to synthetically produce EBC-46 in bulk right in the lab, which opened the door for accessing non-natural and potentially superior analogs.

Stunningly, some analogs deployed in the new HIV-focused study reversed latency in 90% of treated cells – a dramatic four-fold increase over the most powerful latency reversing agent demonstrated to date, bryostatin, which activates only about 20%. “Our studies show that EBC-46 analogs are exceptional latency reversing agents, representing a potentially significant step toward HIV eradication,” Wender said.

The new findings are but the latest in a line of fruitful research involving EBC-46. A medication based on the compound received Food and Drug Administration approval in the United States in 2024 for treating soft tissue sarcomas – a kind of cancer – in humans. That approval followed from approved use in veterinary medicine, where the drug has an 88% cure rate for mast cell tumors in dogs.

Building off their success with HIV cells, Wender and colleagues have moved their research into animal models of HIV, with the ultimate goal of human clinical trials.

“The fact that we may be able to make a dramatic difference in people’s lives with EBC-46 is what keeps us up late at night and gets us up early in the morning,” Wender said.

For more information

Co-authors of the study include Jose A. Moran and Matthew D. Marsden of UCI and Jocelyn T. Kim and Jerome A. Zack of UCLA.

This story was originally published by Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences.