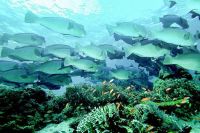

As simple as it is to understand the concept of biodiversity – the variety of species in an ecosystem – the reality is mind-blowingly complex. Organisms big and small can have tremendous effects on their habitats and relate to one another in surprising ways, such as microscopic fungi that help feed our biggest trees. This means that efforts to stall and even reverse ongoing declines in biodiversity require careful solutions and meticulous study of ecosystems and their occupants.

Peering in on the microbial world of nectar in one lab and modeling government programs in protected portions of the Amazon in another, Stanford’s research on biodiversity is, itself, diverse. Our researchers bring to light fundamental discoveries that help us define biodiversity and explore why species disappear. They also offer unique perspectives on how to conserve the natural world, taking into account how it is now and how it will likely be in the decades and centuries to come.