Mornings in Koror, the capital of the Republic of Palau, offer a striking scene, as the sun reflects off limestone karst formations that jut out of the sea floor and lush tree-covered mountains that fill the horizon.

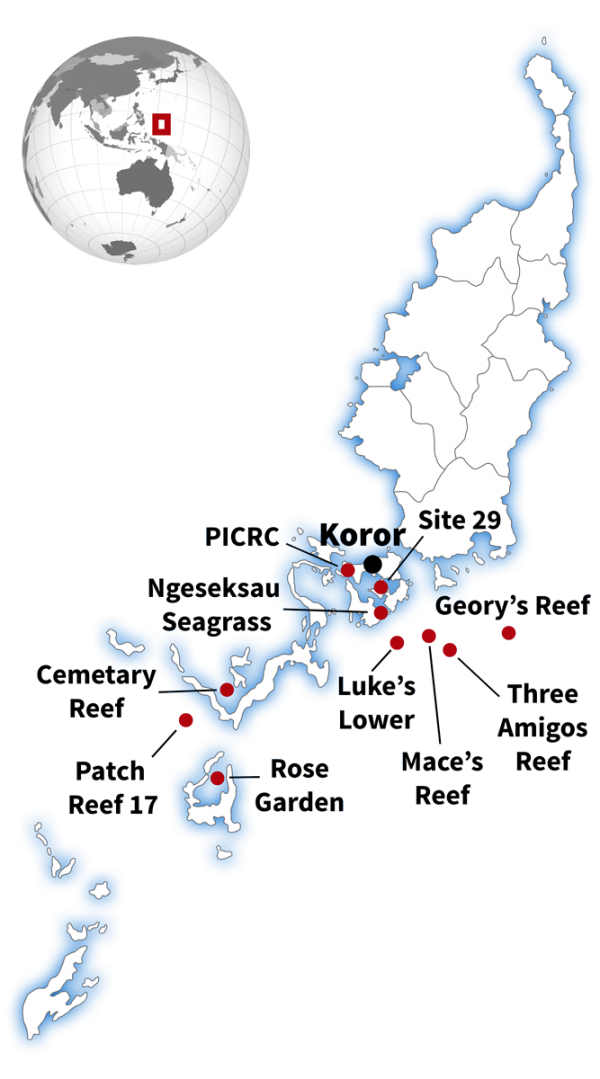

At daybreak, 18 Stanford undergraduates participating in the Bing Overseas Studies Program seminar Ecology and Management of Coral Reefs of Palau load snorkel gear onto speedboats that take them through a network of channels to different coral reef sites between the country’s 340 islands. From low-oxygen basins and tourist-trampled reefs to shallow lagoons and extremely hot environments, Palau hosts an assortment of ecosystems seldom found in such close proximity.

Video by Kurt Hickman

Palau boasts some of the clearest water on Earth and comprises part of the coral triangle, where reefs grow quickly, diversify into a cornucopia of shapes and colors and fight hard for survival. Unlike other parts of the world that are suffering the detrimental effects of ocean acidification and other human impacts, Palau hosts a range of coral sites, from struggling to thriving. And that makes it an ideal place for studying how humans are impacting the planet.

“Some of the places where we’re working are, in a way, the way of the future, the ocean of the future,” said Rob Dunbar, the W.M. Keck Professor in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). “Some of the inshore waters of Palau are both warmer and more acidic because of natural processes, so much so that the water today has chemical and thermal conditions like we expect many other reefs to experience after 100 years of global change.”

Dunbar, a professor of Earth system science, is one of the instructors for the seminar, offered every other year, that introduces students to interdisciplinary oceanography and the chemical, physical and biological interactions that drive the region’s biodiversity.

The curriculum is driven partly by the students, who are tasked with developing their own research projects and delivering results by the end of the three-week program. For some, it’s the first major research project they will conduct as undergraduates. It can be one of the most formative experiences during their time as undergraduates.

Image credit: Rob Dunbar

In the water every day

Program participants are based at the Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRC), the nation’s leading marine research institution. Students complete required reading before arriving and during the first week of the program in Palau; they learn in classrooms about the physical, chemical, biological and ecological aspects of coral reefs, as well as how marine conservation works in the real world.

The lead instructors are Dunbar from Stanford Earth and Stephen Monismith, the Obayashi Professor in the School of Engineering. Other lecturers and researchers join parts of the program, including Steve Palumbi, the Jane and Marshall Steel Jr. Professor in Marine Sciences at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Station; Jeremy Bailenson, the Thomas More Storke Professor of Communication at Stanford; and researcher Robert Richmond of the University of Hawai‘i and the Center for Ocean Solutions. Classroom sessions and afternoon field trips offer an interdisciplinary training to prepare the students to independently plan and develop their research projects.

After the first week, the professors embrace the motto “in the water every day.” Splitting off into different boats based on their project needs, students spend at least half the day exploring underwater ecosystems.

“To me, it’s almost impossible to understand what a coral reef is without seeing one – you can look at pictures, you can study theories of why coral reefs look the way they do, but it just doesn’t come close to having the impact of being there on site.”

—Rob Dunbar

Professor of Earth System Science

Video by Tobin Asher & Elise Ogle, Virtual Human Interaction Lab

“I’ve been teaching in the field all my life and I have four field programs running at Stanford now,” Dunbar said. “To me, it’s almost impossible to understand what a coral reef is without seeing one – you can look at pictures, you can study theories of why coral reefs look the way they do, but it just doesn’t come close to having the impact of being there on site.”

The students come from diverse backgrounds, and while some were attracted to the program because of a previously established love of the ocean, others went snorkeling for the first time in Palau.

Heidi Hirsh, doctoral candidate in Earth system science, examines a pincushion sea star. (Image credit: Griffin Hill)

“I was blown away,” said Aiden McCarty, Biology ’19. “I’ve never experienced coral reefs myself before coming to Palau, and experiencing it with other Stanford students, seeing all the different coral species and not really knowing what they all are and what they do, was just incredible. You can’t get that kind of experience on Stanford’s campus.”

Learning through fieldwork about coral reefs, which Dunbar describes as “the Amazon rainforest of the ocean,” is a journey for the students. Puzzle pieces come together as they begin to understand how fish species interact with different habitats, why certain corals are competing with one another through marine chemical warfare, and how corals contribute to nutrient cycling and the greater oceanic ecosystem.

“This course creates an interactive mode of learning when we’re together in the field – we don’t have the distractions of the internet, Facebook, email, going from one class to the next where you’re constantly distracted,” Dunbar said. “We’re here together for this short period of time focused on one thing: the corals of Palau.”

Image credit: Kurt Hickman

People first

In addition to its biodiversity, one of the main reasons Stanford faculty members have been bringing students to Palau since 2013 lies in the nature of the maritime nation itself. The tiny islands with a population of about 20,000 represent the perfect case study for a coupled human and natural system – what links humans’ economic and social behavior to natural subsystems of the planet, like hydrology, biology and the atmosphere.

“No matter what your major is at Stanford, you can find something in a class that examines how people intersect with a natural environment,” Dunbar said. “It may be tourism, resource extraction or conservation, but there’s something for every student.”

The course focuses on the idea that one important purpose of conducting research is to be able to apply the findings to policy. In Palau, where the main commercial center, Koror, is about 3 square miles, the connection between research and government is tangible and transparent.

“I was really impressed, even inspired, by the attitude that Palauans have toward their reefs,” said participant Nick Mascarello, Earth Systems ’18. “It seemed like everyone we talked to had a real sense of the importance of reefs and why it’s so crucial that nations like Palau do everything they can to protect reefs from all of the many threats that they face.”

By interacting with boat drivers, PICRC scientists, tribal leaders and political influencers, students learn how the Palauans depend on the ocean for their food and livelihood. The country’s unique culture and approachable governance give the students exposure to politicians that would be unheard of in the complex bureaucratic system of a large country like the United States.

The president of Palau spoke with students about the importance of coral reef research. (Image credit: Kurt Hickman)

“We had a chance to meet with the president of Palau, Tommy Remengesau. One of the things he said was something like, ‘The world becomes a better place when we listen to the scientific community.’ To hear the president of a country, a politician, say that – especially in this day and age – was just so refreshing.”

—Nick Mascarello

Earth Systems ’18

“We had a chance to meet with the president of Palau, Tommy Remengesau,” Mascarello said. “One of the things he said was something like, ‘The world becomes a better place when we listen to the scientific community.’ To hear the president of a country, a politician, say that – especially in this day and age – was just so refreshing.”

The students also visited the U.S. Embassy and spoke to the ambassador to Palau. With those experiences, they incorporate the knowledge that their work could have real impacts on Palau’s conservation policies as they partner with their classmates and develop independent research projects based on their interests.

“The students really determine the trajectory of the class,” said Galen Egan, a PhD student in civil and environmental engineering and one of the two teaching assistants from the 2017 course in Palau. “The program also taught me a lot about planning my own research – it’s going to make me think more about how to apply findings to policy and how to communicate findings not only to other scientists but to the public at large.”

Image credit: Nick Mascarello

Diving deep

In 2017, the students’ research projects explored coral resilience to high ocean temperatures, the physics of sea flow and its impacts on seagrass beds, the density of coral skeletons, behaviors of fish communities, and the characterization of oxygen concentrations in different parts of the ocean. Stanford faculty members Palumbi, a marine biologist, and Bailenson of the Virtual Human Interaction Lab, joined parts of the program to contribute their expertise and conduct their own research, adding to the already low ratio of students to professors.

Student research: Surviving warming waters

With ocean waters warming globally, undergraduate Griffin Hill, Biology ’17, decided to focus his research project on which corals are most successful under warmer conditions.

Go to the web site to view the video.

“We’re comparing a number of species and nine different sites to see which do best under these circumstances and which may be worth investigating further through genetic analysis or transplant experiments,” he said.

Hill brought coral samples back to the onshore lab for observation in biology Professor Steve Palumbi’s heat stress tanks. For each sample, he put one portion in a control tank and subjected the other to a much warmer version of the diurnal cycle they experience on the reefs, with the sun heating up water trapped over the reefs during the day and then cooling down at night.

Hill then assessed the samples and rated them for bleaching. “We’re finding that corals here can survive even seven, eight or nine days in a tank that’s a rampant 35 degrees Celsius, which is about the temperature of a hot tub,” Hill said. “Even though that’s well beyond what they’re experiencing out on the reefs here, they’re surviving, and that’s really interesting and a major point of optimism for the future.”

“Palau was really an incredible place to set up and run an independent research project,” Mascarello said. “The other research activities that I’ve done so far have more or less been talking to a professor that says, ‘OK, here’s a project for you. Let me walk you through it’ – it was already formulated.”

Mascarello’s project involved observing behaviors of damselfish populations, an idea he formed while snorkeling and noticing how certain fish tended to associate with microhabitats on the reef. With guidance from Richmond of the Center for Ocean Solutions, he developed a plan to conduct a biological survey to assess how damselfish communities vary among distinct reef habitats with different characteristics.

Nathaniel Buescher, graduate student in civil and environmental engineering, checks GPS coordinates while searching for coral samples. (Image credit: Kurt Hickman)

A student measures a coral as part of an independent research project. (Image credit: Kurt Hickman)

Undergraduates Natasha Batista, Marianne Cowherd and Holly Francis deploy an ADV (Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter) to measure current velocity over the seagrass bed. (Image credit: Heidi Hirsh)

Undergraduate Alex McKeehan collects a sample for his coral density project. (Image credit: Kurt Hickman)

“I had the autonomy to come up with my own ideas, make my own observations, and then actually go through the process of bouncing ideas off of some of the faculty there and test out some different methods,” Mascarello said. “It was really valuable for me as someone that’s a developing scientific researcher just to be able to go from ground zero on a project and see it all the way through.”

He partnered with classmate Neil Singh, Symbolic Systems ’18, and they recorded observations along belt transects. Since most damselfish do not become startled when humans swim up to them, it’s fairly easy to identify a group of fish associating with a microhabitat, record the coral species they’re inhabiting, then take a measurement of the coral, Mascarello said.

Using high-tech equipment and data science

In addition to transects and measuring tapes, equipment such as heat stress tanks, instruments that measure oxygen concentrations, water pressure sensors, biogeochemistry tools and ocean current meters allow the students to stretch the boundaries of their research projects.

Student research: Counting coral

One research team, composed of Amy Bolan, Isabella Badia-Bellinger, Ariel Bobbett and Lilli Carlsen, measured the number of small coral at nine research sites as a way of learning how different environments effect young coral. Some of the sites have been struck with an increasing number of typhoons in recent years. Others have seen a large amount of tourism, and another region is accumulating sedimentation due to nearby agriculture and development. The student researchers found that areas with sedimentation had fewer small coral than the other locations.

Go to the web site to view the video.

“One of the unique things about this class is that it allows us to bring a lot of high-tech, modern equipment that hasn’t been used much to study coral reefs and lets us learn things that in some cases no one knew before,” Dunbar said.

McCarty’s research on deep oxygen-depleted columns of water in Nikko Bay involved using a 60-pound instrument that measures conductivity, temperature, oxygen and depth.

“I’ve been talking a lot to the professors about how to progress with the data I’ve collected so far and they definitely think we’ve found publishable results,” McCarty said. “Being able to share that with the world in that way would be really fantastic.”

Finding solutions

During the final days of the program, the students crunch their data and present their research results to the Stanford faculty and PICRC scientists for feedback.

“When the students present on their project results, I’ve asked every one of them to say how their work relates to things that Palauans might think about in terms of maintaining the health of their reef ecosystems into the future,” Dunbar said.

Student research: The physics of water

Natasha Batista, Earth Systems ’18, and Holly Francis, Ocean Engineering ’19, were curious about the ocean currents that move nutrients and sediments across seagrass beds and throughout the bay. Part of their interest in this question was due to the fact that it required understanding the ocean as a system across disciplines.

Holly Francis and Heidi Hirsh carry out a research project in seagrass beds while in Palau. (Image credit: Kurt Hickman)

“Seagrass has largely remained unstudied in Palau compared to coral reefs, yet it may comprise a highly influential ecosystem with the potential to locally counteract ocean acidification,” Francis said. These marine plants form underwater meadows that can create drag in the water column during different oceanic conditions.

Batista and Francis, along with Stephen Monismith, professor of civil and environmental engineering, and teaching assistant Heidi Hirsh, a doctoral candidate in Earth system science, measured the velocity of water moving through the water column above seagrass beds at different heights.

The team processed that data to learn that the tidal flow in the bay has a net flow out toward the ocean and that the bottom drag is relatively much weaker when flows are stronger because of the way that seagrass is bent by flow.

“This information is important if you want to get a holistic understanding of how Nikko Bay functions,” Batista said. “If people want to look further into Nikko Bay and how the seagrass beds can be a buffer or nursery for corals and larger species, you want to understand all components of it.”

The students’ journeys are not over when the course concludes. The professors hope they retain a new appreciation for some of the crucial roles coral reefs play on the planet – hosting food sources on which humans are dependent and protecting coasts from the impacts of storms – as well as an understanding of the intrinsic way the Palauan people value and respect their environment.

“The real product is some sense of what they might do in the future,” said Monismith. “Some students have really changed since they’ve been here.”

Three students from the program stayed in Palau to continue research for projects they conceived during the class, and the others carry with them the enduring knowledge of experiencing an immersive, place-based education.

“This region has been remarkably resistant to change like bleaching events, which is important moving forward not only because it allows us to experience biodiversity, but because a resistant reef is something that will be important in a world of climate change,” McCarty said.

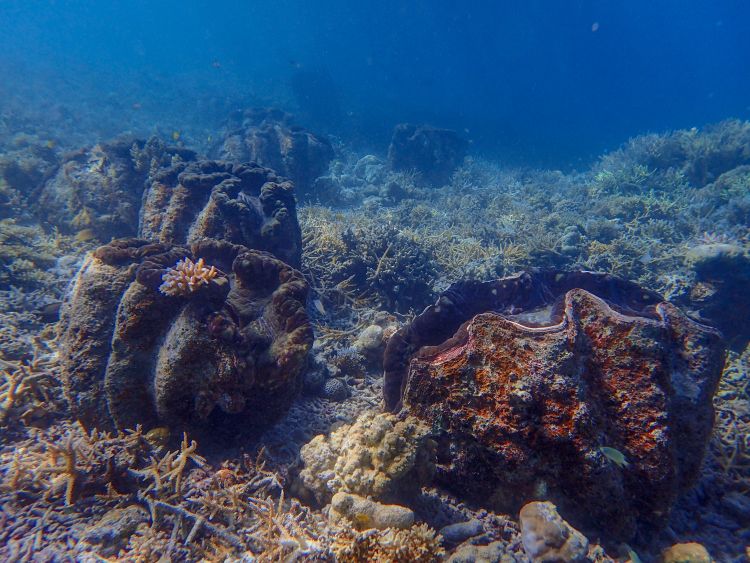

Following the presentations, the students joined together for a final day of exploration by visiting some of Palau’s best-known coral sites: Milky Way, where silty water overlying living coral is “proof of the adaptability of coral,” according to Dunbar; Rose Garden, where students found an octopus; Clam City, where they swam above giant clams; and Blue Corner, where they saw sharks.

Students gather around an octopus at the Rose Garden. (Image credit: Natasha Batista)

Giant clams of Clam City. (Image credit: Heidi Hirsh)

“During the research period, we were a bit separated on most days, going to different places,” Mascarello said. “It was so much fun to come together again after everyone had learned so much and see that everybody had a newfound appreciation for all the life there and the reefs.”

During that excursion, the students also shared reflections about what they learned and how their work could help save the corals.

“Being in Palau, you feel really small and really in awe of what’s beneath you – the number of fish you see, the absolute beauty of the corals,” Egan said. “It gives you the sense that they are something that’s worth protecting.”

Image credit: Rob Dunbar

Produced by Amy Adams