The Big Game Disaster of 1900

With no stadium seats available, hundreds of fans clambered onto a rickety rooftop nearby. What happened next became the worst accident ever at a U.S. sporting event.

Buried deep in the 121-year tradition of the annual Big Game between the Stanford Cardinal and the Cal Berkeley Golden Bears is an obscure tragedy that took the lives of nearly two dozen spectators and injured many more. But as Sam Scott writes in a 2015 article for Stanford magazine, the catastrophe remains the deadliest sporting disaster in the United States, yet one that is forgotten in the histories of Berkeley and Stanford.

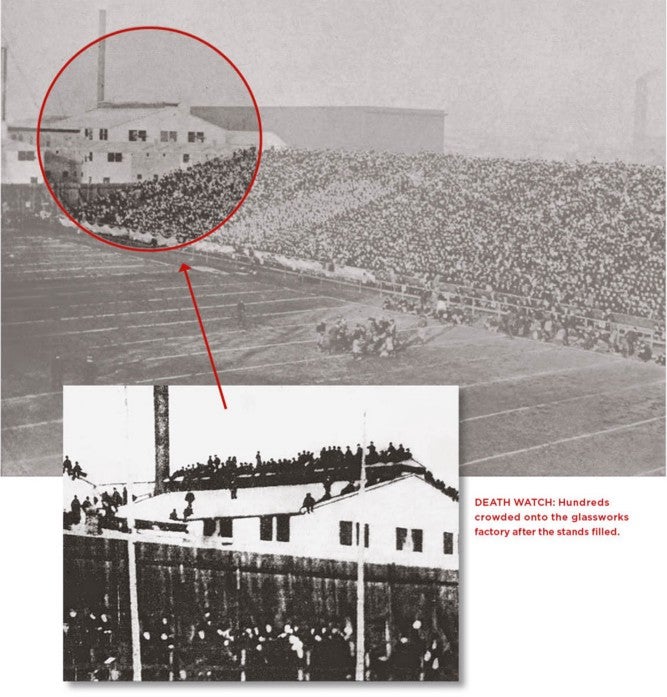

After the stadium filled up, hundreds of spectators crowded onto a rickety rooftop to view the Big Game in 1900 in San Francisco. (Image credit: John E. Hare/San Francisco Examiner)

On Thanksgiving Day, November, 29, 1900, the rivals met at a field at 16th and Folsom streets in San Francisco’s Mission District for the tradition’s ninth matchup. Next door, looming over the field’s north side, was the industrial site of the San Francisco and Pacific Glass Works, which housed a massive brick furnace. “Inside its white-hot walls, 15 tons of molten glass seethed, tended by a skeleton crew,” writes Scott.

Back at the field, fans from across the region began to fill the stands at around 10:30 a.m. But Scott explains that for those unwilling or unable to pay $1 for a ticket, “the rush was on to find another way to see the spectacle.”

Swarms of fans, mostly boys and young men, rushed to the flimsy roof of the glassworks building next door, anxious to see the kickoff at 2:30 p.m. Soon, the rooftop was filled with spectators – about 400 according to one estimate – who had a view from one end of the field to the other.

Scott writes:

“Twenty minutes after kickoff, the crowd was tense as Cal made its first foray deep into Stanford territory. Then a crash from the field’s north side brought play to a halt. The roof of the glassworks had collapsed like a gallows’ trap. Necks craned. Players stood out. No one could see exactly what had happened. Then, by one account, a Berkeley fan, fearing a Stanford diversion, yelled, ‘It’s a job,’ and all eyes returned to the ball. The game continued as if nothing had happened, the bands and cheers overwhelming the screams next door.”

Scott writes that a worker inside the factory had been raking the furnace fire – estimated to be 500 degrees – when bodies began raining down from 50 feet above. “It was a horrible experience standing there beside a hellpot and seeing human beings roast to death,” one factory worker was later quoted.

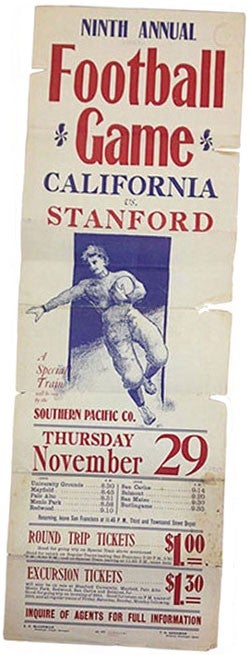

A ticket from the ninth annual Big Game in 1900. (Image credit: Stanford University Archives)

Scott continues:

“Some were lucky to grasp rafters, holding on for life as death massed below. ‘Bodies were falling like hail,’ one man said. ‘As I clung there I saw the poor fellow who had been chatting with me strike the furnace. He curled up like a worm in that heat.’”

The chaos had little impact on the game. Due to noise, information about what was happening next door was slow to spread to the fans and players inside the stadium. Stanford would go on to win 5-0.

The tragedy claimed the lives of 23 people and injured many more. Those who perished lived within walking distance of the stadium, including the youngest, 9-year-old Lawrence Miel. News of the catastrophe dominated local media and even made the front page of the New York Times. But the coverage was “bizarrely bifurcated” by today’s standards as front pages reported the horrific scene while sports sections reported typical game stories without any quote from coaches or players about what had happened.

Scott writes:

“The student newspapers took an even stranger tack. Writing about the game for the following Monday because of the holiday weekend, the Stanford Daily featured a 1,500-word front-page story about the victory without so much as a word about the disaster 200 feet away. (The Cal paper reacted in similar fashion.) Indeed, the only reference to the tragedy was a brief item a week later about rumors of a Christmas Day rematch to raise money for affected families, a game that never happened.”

Read Scott’s full article in Stanford magazine.