In brief

- The Native American Cultural Center began in two rooms of Old Union in 1974 and is now a thriving hub for Stanford’s Native and Indigenous students.

- Today, the NACC occupies the ground floor of Old Union Clubhouse and employs a team of student staff, including archivists, wellness coordinators, and office and programming assistants.

- A digital story map called “Indigenous Excellence at Stanford: Histories, Voices, and Perspectives from the Past 50 Years,” explores the center’s creation and legacy.

In the 1970s, a group of Stanford students acquired two dusty and cluttered rooms on the ground floor of Old Union and established the Native American Cultural Center (NACC). In the decades since, the space has evolved into a vibrant hub for numerous Native student organizations on campus. The NACC has also helped define the Stanford experience for Native and Indigenous students and changed the cultural fabric of the university.

“The center has been a great asset for Native students and the broader Stanford community to participate in its activities and programming,” said Ben Atencio, ’77, who helped establish the center when he was a Stanford undergrad.

This year marks the center’s 50th anniversary. To commemorate this milestone, a digital story map titled Indigenous Excellence at Stanford: Histories, Voices, and Perspectives from the Past 50 Years explores its creation and legacy.

A burgeoning community

Stanford’s relationship with Native people dates back to the university’s founding. The campus is located within the traditional territory of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, on land purchased by Leland Stanford. John Milton Oskison, a member of the Cherokee Nation who enrolled in 1894, was among Stanford’s first Native students and the first Native American to graduate from the university.

In the late 1960s, anti-war protests and a growing awareness of race and representation swept American college campuses. The Occupation of Alcatraz – a 19-month protest by Native people on the Bay Area island – also inspired Native students at Stanford and across the U.S. to mobilize.

At that time, Stanford had fewer than 10 Native students, but their advocacy led the university to increase their representation. Constance Owl, ’18, interim director of the NACC, said a surge in Native student enrollment began in 1970.

“Twenty-two Native students enrolled that year and when they got to campus is when the Stanford American Indian Organization, or SAIO, formed and took off,” Owl said.

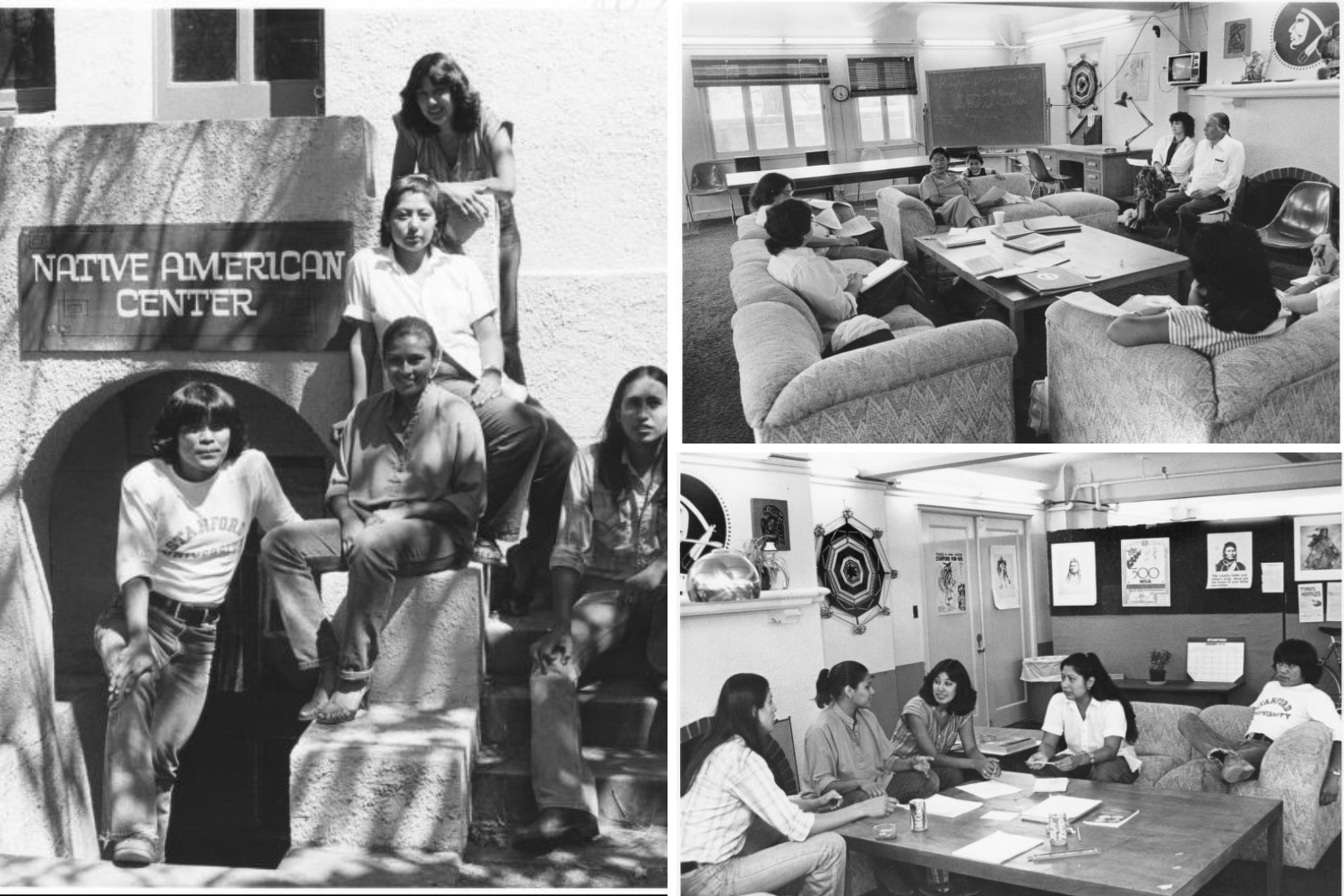

Native Stanford students at the NACC in the 1970s. | Courtesy Native American Culture Center

The students’ impact was immediate. With support from outgoing president Wallace Sterling, incoming president Richard Lyman, the student senate, and university staff, the Native students signed the first petition against the Stanford “Indian,” ending a years-long effort to banish the mascot. To bring a more authentic representation of Native American cultures to campus, they launched the first Stanford Powwow in 1971, which in turn helped support Stanford’s enrollment of more Native students in the years that followed.

As the Native student community grew, so did their need for a dedicated space. They wanted, “a space at Stanford that felt like home, that felt representative of them,” Owl said.

Initially, the students used temporary gathering spaces, including a house on Alvarado Row and later the Fire Truck House. In 1973, they moved into part of the ground floor of Old Union – then called the women’s clubhouse – where they established the NACC.

A home at Stanford

In the fall of 1973, Atencio was a frosh from New Mexico and serving as the NACC’s center coordinator. He remembers helping his fellow students move into the two-room space that November.

“Before us, it had been a storage facility, so it was really dusty,” Atencio recalled. “But we cleaned it up, moved out the old furniture, built some partitions, and put in some desks, shelves, and couches.”

The center has been a great asset for Native students and the broader Stanford community to participate in its activities and programming.”Ben Atencio, ’77

Developing the NACC was an organic and collective effort. The students hung flyers around campus asking others to help sand the floors and paint the walls. Staff and administrators offered support, including Gwen Shunatona, the first university staff member hired to serve as assistant dean and advisor of Native students, and Alan Strain, a former assistant dean of student affairs who also served as an interim assistant dean for Native American affairs. By February 1974, the space was finally coming together, so the students held a reception to mark the center’s opening.

“It was a big deal for us because we didn’t have many events until then,” Atencio said. “And it was the first time Native students at Stanford – undergrad and grad students – really got together to get to know each other.”

The NACC was particularly helpful for first-year students transitioning to a new environment. “At this time, many of the Native students at Stanford were coming from reservations or very rural communities. So, coming to Stanford was often a major cultural shock for them," Owl said.

In the NACC’s early years, before professional staff joined the center, undergraduates served as Tecumseh Fellows to coordinate programming, work with the university on student recruitment, serve as peer counselors, and lead the vision for the center.

Campus contributions

Today, the NACC occupies the entire ground floor of Old Union Clubhouse and employs a team of 15 student staff members, including student archivists, librarians, wellness coordinators, and office and programming assistants. It is supported by a team of professional staff members, including assistant deans and associate directors Denni Woodward and Greg Graves. It has become a popular gathering space for many Native Americans, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Indigenous Pacific Islanders at Stanford. There, students can study, receive academic and peer support, network, socialize, and plan events.

The center’s influence has reverberated across the campus, helping to define the Stanford culture. For example, Powwow has become one of the university’s most popular annual events, welcoming thousands from across California and beyond to celebrate Native and Indigenous traditions. It is also one of the largest Powwows in the nation and the largest student-led Powwow anywhere.

There are about 450 Native and Indigenous students at Stanford, including undergraduate and graduate students, who together represent over 50 Native nations and island communities. The center's ongoing commitment to fostering a sense of community and belonging continues to shape the experiences of Native and Indigenous students at Stanford. This fall, the NACC will host the Stanford Native Immersion Program, a six-day off-campus pre-orientation retreat for Native frosh and new transfers entering its 35th year.

Atencio, Shunatona, and other Native alumni and former staff members returned to campus in February for an event at the NACC to reflect on its influence over the decades. Atencio said he’s proud to see the center thriving all these years later.

“The NACC is a real living space for culture and traditions,” he said. “And I’m very proud of the center and pleased to see that the community keeps growing.”