This year, amid a national reckoning with systemic racism in America, California legislators voted to place Proposition 16 on the November ballot. The initiative, if approved, would allow the state’s public universities and government offices to consider race, gender or ethnicity in making admissions and contracting decisions.

In other words, it would reinstate affirmative action – a term whose meaning has changed in the years since it first appeared in a 1961 executive order signed by President John F. Kennedy, which instructed federal contractors to ensure that job applicants and employees are treated “without regard to their race, creed, color or national origin.”

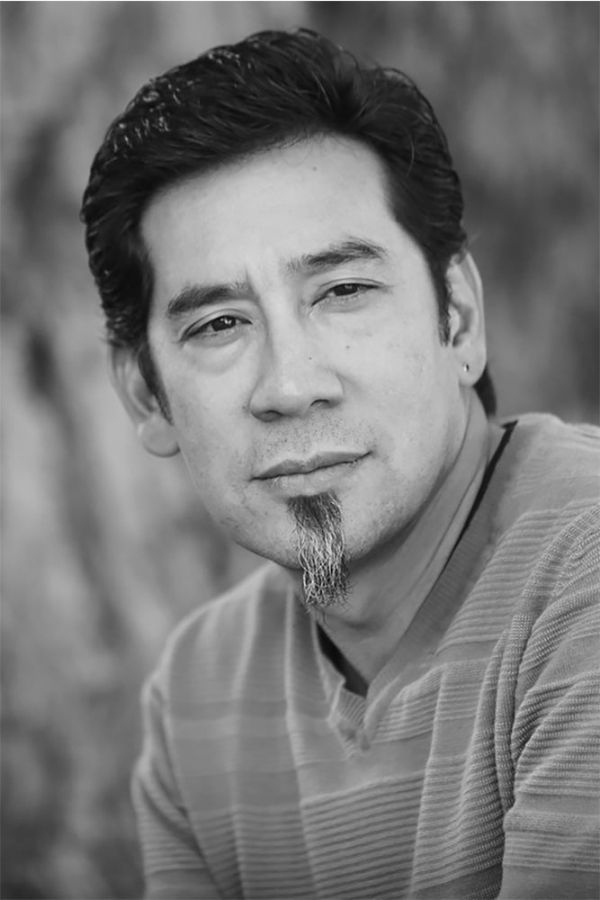

Anthony Lising Antonio is an associate professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education whose research focuses on equity issues in American higher education. He teaches a course on multicultural issues in higher education, including the impact of Proposition 209, the California ballot measure that banned affirmative action in 1996. His work has been cited in amicus briefs submitted to the Supreme Court for several affirmative action cases such as Gratz v. Bollinger, Grutter v. Bollinger and Fisher v. University of Texas.

Here, he talks about how Americans’ understanding of affirmative action has shifted since the Civil Rights Movement, the effect Proposition 209 has had on higher education in California and alternate ways for universities to ensure a diverse student body.

When the term “affirmative action” was introduced in the 1960s, it didn’t seem to have provoked the kind of controversy that it does today. How has the concept changed over the years?

In the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, affirmative action was conceived as a forward-looking corrective to societal racism and discrimination, particularly in education and employment. I think of it as the antithesis to Jim Crow. Where Jim Crow maintained and widened inequality through statutory segregation grounded in racism, affirmation action sought to remedy those conditions by promoting integration.

Since Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978, however, when affirmative action was challenged in the Supreme Court as a violation of the rights of white college applicants, views of the policy have become increasingly polarized. Rather than being seen primarily as a benefit for underrepresented applicants, it was now posed as discriminatory towards whites. Proposition 209 passed with only a 55-45 majority, which reflects that polarization.

What impact has the 1996 ban had at California universities?

The removal of affirmative action in admissions was a double-whammy for underrepresented students of color. Not only did enrollments of Latinx, African American and Native American students fall drastically at the UCs, so did applications. The removal of affirmative action also sent a message to those students that they were not welcome on a UC campus.

Demographic change has allowed Latinx applications and enrollments to recover over the proceeding decades, but this hasn’t been the case for African Americans or Native Americans. Even worse, the discrepancy between each group’s UC enrollment compared with their representation in the population has increased. For all three groups, underrepresentation has gotten worse at the UC and at other universities in states that have banned affirmative action.

Is Proposition 16 a meaningful step toward expanding access?

Given the progress toward equal representation that was made prior to Proposition 209, Proposition 16 should make a positive impact. Many of the state’s most talented students who felt unwelcome at the UC will remain in-state or choose the UC over the private institutions that opened their doors to them after Proposition 209.

But Proposition 16 will fall short of its promise to promote a more equitable society if universities treat affirmative action as a job well done. The task of equity continues with the support and resources provided to these students for success in college – the kind of support that students in richer, private institutions already receive.

If voters reject Proposition 16, what legal avenues can educational institutions pursue to ensure more diversity in admissions?

Researchers and policymakers have looked at alternatives to affirmative action over the last 25 years. Class-based affirmative action gives additional admission preferences to low-income applicants. “Top X percent” plans grant admission based upon class rank in a student’s high school, so if you’re in the top 10 percent of your class, you get in. At the UC, campuses mounted greatly expanded efforts to recruit applicants of color in the wake of Proposition 209.

The research on the removal of affirmative action clearly shows that all of these alternatives cannot provide the racial diversity that affirmative action affords. Still, institutions can and should continue to explore these alternatives and others, such as no longer requiring the SAT for admission.

One very positive result of Proposition 209 – and the Supreme Court challenges to affirmative action that followed it – was the wave of research that illustrates the educational benefits of a racially diverse student body. Diversity exposes students to challenging ideas and perspectives. It contributes to retention in college, satisfaction and the development of what we call prosocial attitudes or behaviors to benefit others. And importantly, it promotes civic engagement. Institutions can take that knowledge to heart and be much more thoughtful in how they promote, structure and curate diversity with their students.

Media Contacts

Carrie Spector, Graduate School of Education: (650) 743-7384; cspector@stanford.edu