As the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic continues to deliver both health and economic blows, hopes are pinned on medical researchers identifying drugs and vaccines needed to stop the virus’s spread, heal those who are sick and ease concerns about returning to a semblance of normal. But the process of developing new medicines is a long one, and at best new vaccines can take more than a year.

Go to the web site to view the video.

Into this landscape enters the newly created Innovative Medicines Accelerator (IMA), which was envisioned to overcome obstacles in developing medicines. The IMA arose as part of Stanford’s Long-Range Vision long before COVID-19 found a foothold in humans, and was designed to aid in medicines for everything from deadly diseases like cancer to rare disorders overlooked by most pharmaceutical companies. But in this time of need, its programs are focused entirely on helping researchers test their ideas about potential medicines for COVID-19.

“Our programs were envisioned before our new priority came along, and that’s the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Chaitan Khosla, Baker Family co-Director of Stanford ChEM-H who is also leading the IMA. “The scale of what Stanford researchers have accomplished in the past two and a half months is unprecedented. Where we are today might not have been so powerful if not for the efforts of people associated with the IMA.”

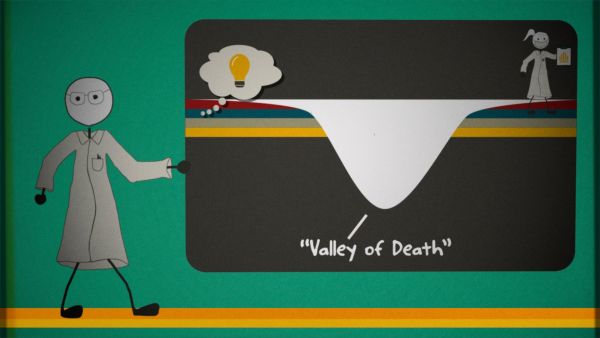

Valley of death

A “valley of death” lies between a good idea in the lab and a drug that can be tested in humans. (Image credit: Farrin Abbott)

The IMA’s programs aid scientists in traversing the so-called “valley of death” – that chasm between a good idea in the lab and the first test of a new drug in humans. This valley, created by a lack of funding and drug development expertise on the academic side and by concerns about financial risk on the industry side, isn’t entirely unnavigable. Many ideas cross the divide each year, but the difficulty adds to the time and cost of developing new medicines.

Stanford faculty who have successfully developed vaccines and drug prototypes were aided by a network of expertise and programs centered in the School of Medicine and in the interdisciplinary life sciences institutes like Stanford ChEM-H, Stanford Bio-X and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. The IMA builds on and expands those resources so more can benefit, while also filling in gaps that have waylaid some projects. These added programs include funding promising early-stage research, adding technical capabilities and expertise and assisting with studies in human tissues to help ensure good ideas discovered in mice will be effective in people.

Building up

The Innovative Medicines Accelerator builds on and expands resources already available at Stanford to create a bridge across the “valley of death.” (Image credit: Farrin Abbott)

The concept of building on existing resources was immediately helpful in responding to COVID-19, particularly the Stanford ChEM-H Knowledge Centers, which are facilities run by staff with deep drug development experience and who provide expertise along with the technical resources.

“If ChEM-H didn’t exist, the first thing the IMA would have to do in order to be successful is create it,” said Carolyn Bertozzi, Baker Family co-director of ChEM-H, and Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

For example, Peter Kim, professor of biochemistry, is making use of the ChEM-H Macromolecular Structure Knowledge Center to learn how human antibodies bind SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, as part of work to develop a vaccine. Jeffrey Glenn, professor of medicine, is one of several researchers developing drug prototypes against various types of viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, with assistance from the ChEM-H Medicinal Chemistry Knowledge Center.

As the IMA considers research funding for COVID-19 projects, it is augmenting these knowledge centers in anticipation of increased need, and adding new ones that fill additional gaps like allowing investigators to screen a high volume of molecules as potential drugs – known as high-throughput screening.

In addition to networking existing facilities, the IMA is expanding space in the Keck Science Building where researchers can safely handle deadly, airborne pathogens, called a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) facility. Researchers including Catherine Blish, associate professor of medicine, are already carrying out experiments in the smaller space to test existing drugs against SARS-CoV-2 in infected cells, and studying the virus’ biology to identify new drug candidates. When it is complete, the expanded space will provide access to more investigators developing COVID-19 medicines and could also aid in addressing possible future pandemics or known airborne pathogens like tuberculosis.

As part of the Long-Range Vision, which emphasizes partnership to accelerate impact, IMA will also form alliances with biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, governments and nongovernmental organizations to exchange knowledge and expertise. These would resemble an existing relationship between Takeda Pharmaceutical Company and Stanford ChEM-H called the Stanford Alliance for Innovative Medicines, in which Takeda provides access to drug development expertise, not generally available in academia, to help potential medicines reach patients more quickly.

Testing ideas in people

In addition to easing the path to drug prototypes, the IMA overcomes another hurdle in developing effective medicines – the fact that many great ideas originate with lab animals like mice or flies but fail when they reach human trials. Khosla calls this a second valley of death.

“If there’s one thing we’ve learned from clinical trials it’s that mice aren’t humans,” said Khosla, who is also the Wells H. Rauser and Harold M. Petiprin Professor in the School of Engineering and professor of chemical engineering and of chemistry.

The challenge has been that investigators used to working with laboratory animals often don’t have the resources or regulatory expertise to access human subjects or tissues. To overcome that problem, IMA will provide funding and expertise and also assist with collecting and storing tissues. (These experiments will have the added benefit of producing new discoveries about human biology.)

Many drugs aren’t effective in humans because they come from ideas developed in laboratory animals like mice, flies and worms. (Image credit: Farrin Abbott)

That approach – which they call Experimental Human Biology – is already being applied toward COVID-19 at the IMA-supported COVID Clinical and Translational Research Unit (CTRU). Here, researchers are gathering blood samples from people with or without COVID-19 and from people participating in trials of existing drugs to see if they are effective against COVID-19. Those samples can help researchers understand how the human immune system responds to an experimental drug, and they are being banked for possible future experiments as investigators have new ideas for medicines or vaccines.

Stanford also has expertise in creating mini organs – including brains, and lung and intestinal tissue – in laboratory dishes. These “organoids” can be used to test ideas in cells representing human biology. Some COVID-19 work takes advantage of such labs-in-a-petri-dish in the form of clusters of cells that mimic the human immune system. Looking beyond the current crisis, Stanford also has banks of stem cells derived from people with different disease backgrounds that can be grown into a range of tissue types.

These programs, which are ramping up now to address COVID-19, will ultimately benefit a range of diseases in need of new medicines or even help prepare for a future pandemic.

“The metrics of success for the IMA are based on impact,” said Khosla. “That doesn’t have to be just in terms of reducing the time or cost of developing a drug. What if you could powerfully benefit the health of one kid with an extremely rare disease? That’s a pretty big impact.”

Khosla and Bertozzi are also members of Stanford Bio-X, the Stanford Cancer Institute and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Kim is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and is the Virginia and D. K. Ludwig Professor of Biochemistry. Glenn and Blish are also members of Stanford Bio-X.

Media Contacts

Amy Adams, University Communications: (650) 497-5908, amyadams@stanford.edu