We teach our children to treat others as they want to be treated, but what about the world around them? As the dominant force driving ecological change, the damage we do to natural life-support systems is eventually visited upon us, perhaps most dramatically in our health. Stanford researchers are exploring how climate change fueled by human-caused emissions is altering the burden of disease, hunger, thirst and mental illness around the world. Their sobering discoveries open a window into understanding, predicting and mitigating these changes.

“The next great health threat has already emerged,” said Paul Auerbach, a professor emeritus of emergency medicine and co-author of the book Enviromedics: The Impact of Climate Change on Human Health. “It’s climate change.”

Climate change’s health impacts are and will be broad. Related drivers such as extreme weather and sea level rise are already contributing to a range of ills from outbreaks of waterborne disease and heat-related illness to respiratory allergies and asthma. Scientists are increasingly able to connect climate change to events such as civil conflict and forced migration that result in injury, mental illness and death on a large scale. The youngest, oldest and poorest among us stand to lose the most.

Pollution from human-caused fossil fuel emissions presents a particularly stark picture. Globally, long-term exposure to indoor and outdoor air pollution is associated with about 7 million deaths annually, according to the World Health Organization. Children under age 5 in lower-income countries are more than 60 times as likely to die from exposure to air pollution as children in high-income countries, according to the World Bank. Regardless of age, people exposed to polluted air for long periods of time are more likely to suffer from diseases such as stroke, lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The next great health threat has already emerged. It’s climate change.

Paul Auerbach

professor emeritus of emergency medicine

“Human-driven changes to the natural world will likely drive the majority of the global burden of disease and other health impacts over the coming century,” said Susanne Sokolow, a senior research scientist at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and co-director of Stanford’s Program for Disease Ecology, Health and the Environment, which brings together researchers in Planetary Health and One Health fields to discover ecological solutions to disease. “We won’t have another chance to get this right.”

Recently, Stanford Medicine magazine hosted a series of stories on global health, and here we expand on ways in which our own health relies on the health of the planet.

Story 1: Climate change influences disease risk

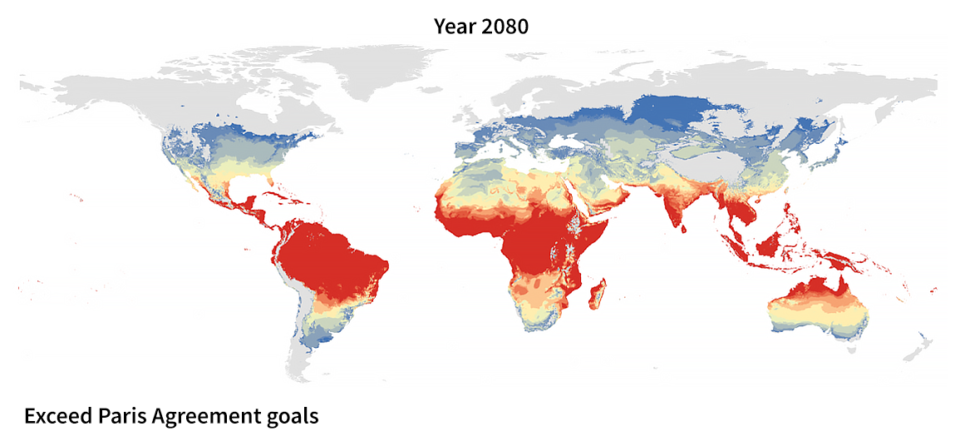

As the globe warms, disease-carrying animals like mosquitoes will roam beyond their current habitats, shifting the burden of diseases. Biologist Erin Mordecai predicted how the normal habitat of the mosquito Aedes aegypti – which spreads virus that cause dengue fever, chikungunya, zika and yellow fever – will expand if the world continues to emit greenhouse gasses at current levels and compared that to a model in which countries work together to not only meet but exceed the Paris Agreement goals. In this comparison, without a check on climate change the mosquitoes will spread to colder regions and will spend more of the year in temperate parts of the world. (Blue regions indicate areas where the mosquitos can only live 1 month of the year and red regions indicate places where the mosquitoes can live year round.)

Story 2: Climate change and hunger

As the climate changes, where plants grow best is predicted to shift. Crops that once thrived as a staple in one region may no longer be plentiful enough to feed a community that formerly depended on it. Beyond where plants grow, there’s also the issue of how they grow. Evidence suggests that plants grown in the presence of high carbon dioxide levels aren’t as nutritious. Eran Bendavid, associate professor of medicine, David Lobell, professor of Earth system science in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, and graduate student Christopher Weyant explored years of healthy life lost due to less nutritious foods if climate change continues unabated. They also explored various interventions, including attempting to meet Paris Agreement goals. Of those interventions, reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere saved the most lives.

The researchers estimated total years of healthy life lost from 2015 to 2050 due to carbon-dioxide-related zinc and iron deficiencies, with different interventions. The researchers’ predictions showed that keeping to the Paris Agreement goals and reducing greenhouse gas emissions results in far better health outcomes than other solutions, such as supplementing nutrients. (Image credit: Yvonne Tang)

Story 3: Climate change and thirst

Jordan is among the most water poor regions in the world, and serves as a case study for the way climate change could impact people’s access to water. A team of researchers analyzed data collected through remote sensing and government surveys and developed computer simulations of droughts under different scenarios. The results showed that if climate change continues unabated, rainfall in Jordan will decline by 30 percent and the occurrence of drought will triple by 2100. In a scenario in which emissions begin to decline roughly in accordance with the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement, drought is still prevalent by 2100 but significantly improved over the other scenario.

The Jordan river valley is at increased threat of drought as the climate warms. However, in a scenario in which the world attempts to hold warming at less than 2 degrees Celsius, the region is projected have significantly less drought than if the world continues emitting greenhouse gasses unabated. (Image credit: Yvonne Tang)

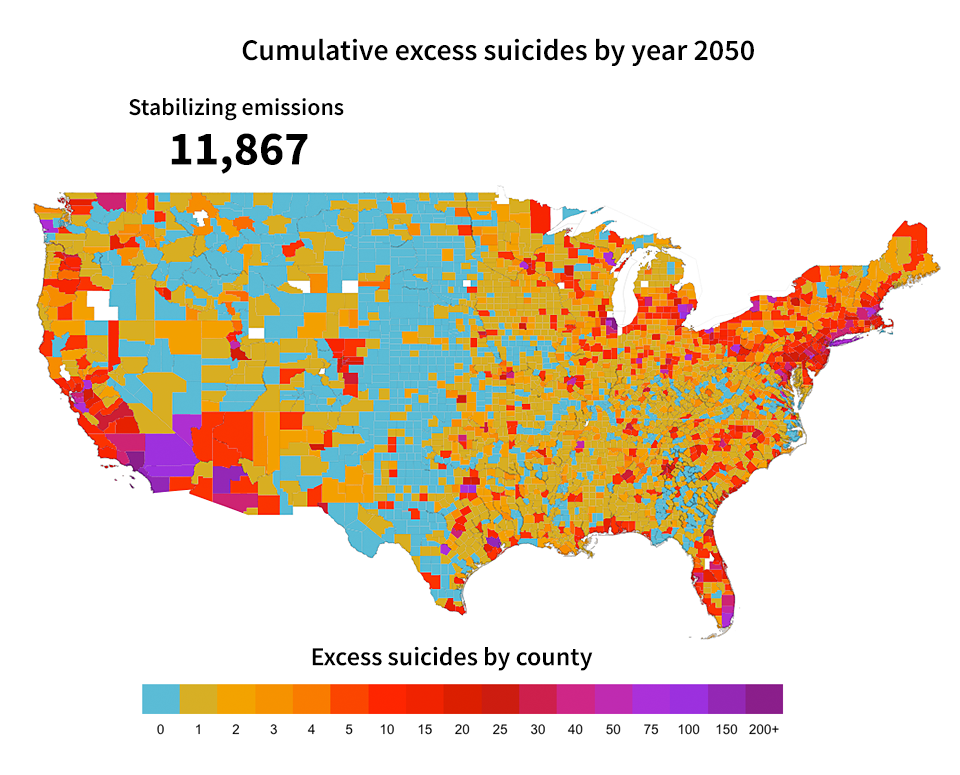

Story 4: Climate change and mental health

As global temperatures rise, climate change’s impacts on mental health are becoming increasingly evident. Stanford economist Marshall Burke and research scholar Sam Heft-Neal found that hotter than average temperatures increase both suicide rates and the use of depressive language on Twitter. They also concluded that socioeconomic status had little to no impact, meaning wealth does not help insulate populations from suicide risk. Using global climate model projections to predict how future temperatures could affect suicide rates, they found that stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions consistent with Paris Agreement goals significantly reduces the number of excess suicides caused by climate change compared to a model where emissions continue unabated.