Proteins are so much more than nutrients in food. Virtually every reaction in the body that makes life possible involves this large group of molecules. And when things go wrong in our health, proteins are usually part of the problem. In certain types of heart disease, for instance, the proteins in cardiac tissue, seen with high-resolution microscopy, are visibly disordered. Alex Dunn, professor of chemical engineering, describes proteins like the beams of a house: “We can see that in unhealthy heart muscle cells, all of those beams are out of place.”

Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, making the biochemical processes of life possible. These workhorses include enzymes, which bind to other molecules to speed up reactions, and antibodies that attach to viruses and prevent them from infecting cells. “Proteins move things around the cell. They transmit signals from outside the cell to change levels of gene expression. They catalyze all of the chemical reactions that make life possible,” says Polly Fordyce, associate professor of bioengineering and of genetics.

Understanding how proteins do all this can help solve fundamental questions of how proteins organize into greater structures and fine-tune their function for applications in medicine, industry, and other areas. These questions inspire Stanford engineers to study the life-enabling molecules from every angle.

Visualizing proteins to uncover their function

A lot of the secrets of proteins are tied to their complex structure, explains Brian Hie, assistant professor of chemical engineering. At a basic level, proteins are made up of long chains of amino acids. These chains often create helices, pleats, and folds to form a three-dimensional structure. Multiple proteins can also bond together, forming a protein complex. The way proteins are organized impacts protein function.

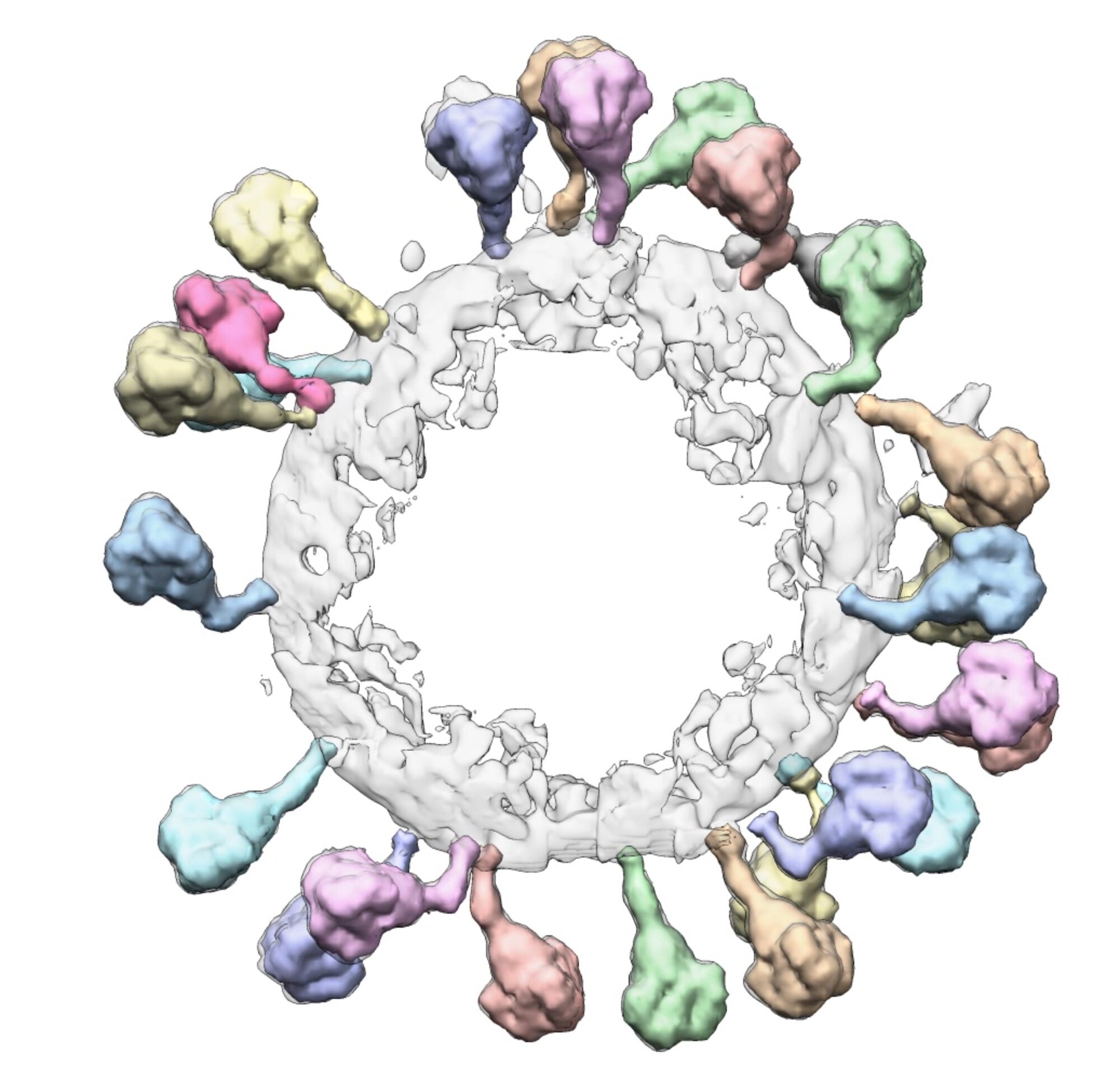

To better understand this organization, Wah Chiu, professor of bioengineering, of microbiology and immunology, and of photon science, studies proteins at high resolution – even down to the scale of an individual amino acid. A method he helped develop, called cryogenic electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, allows researchers to see proteins like never before possible. Previous imaging techniques required crystallizing cells into a repeating pattern, but cryo-EM flash-freezes the protein to preserve its natural organization. The electron microscope captures images of the frozen protein at multiple angles, and the photos can be combined to create 3D models.

The microscopy method has enabled a closer look at key processes, such as the enzyme “assembly lines” that Chaitan Khosla, professor of chemical engineering and of chemistry, studies. These groups of proteins can produce antibiotics with mind-boggling speed and selectivity, says Khosla – holding clues potentially useful for manufacturing drugs. Using cryo-EM to see the assembly line, compared to other methods, was like the difference between seeing an automobile factory on a weekday versus a weekend. “When you can see the assembly line actually make its own automobile,” he says, “you get a much clearer sense of what it takes to build an automobile.”

Testing protein properties to understand disease and develop therapies

Of course, we can’t learn everything about proteins just from observing them. Researchers must also run tests to see how proteins react under certain conditions, to help answer questions about their roles in living systems.

And to run tests, it helps to have a lot of proteins at your disposal. James Swartz, professor of chemical engineering and of bioengineering, is pioneering cell-free protein synthesis. Historically, scientists have inserted a target protein’s DNA into E. coli, using the bacteria to churn out copies of that protein. But the process can be slow and sometimes fails to reproduce the protein’s precise structure.

In cell-free protein synthesis, cells are ripped apart at very high pressure, making it possible to extract the components such as ribosomes needed for protein production. Then, cellular energy supplies can be exclusively focused on pumping out protein. The cell-free approach can also produce certain types of molecular bonds that are otherwise challenging to make.

One application Swartz is working on is “virus-like particles” – manufactured virus-shaped protein assemblies, featuring spikes and an internal cavity that can transport materials to a target location. One day, these “virus-like particles” may help deliver vaccines and cancer treatments.

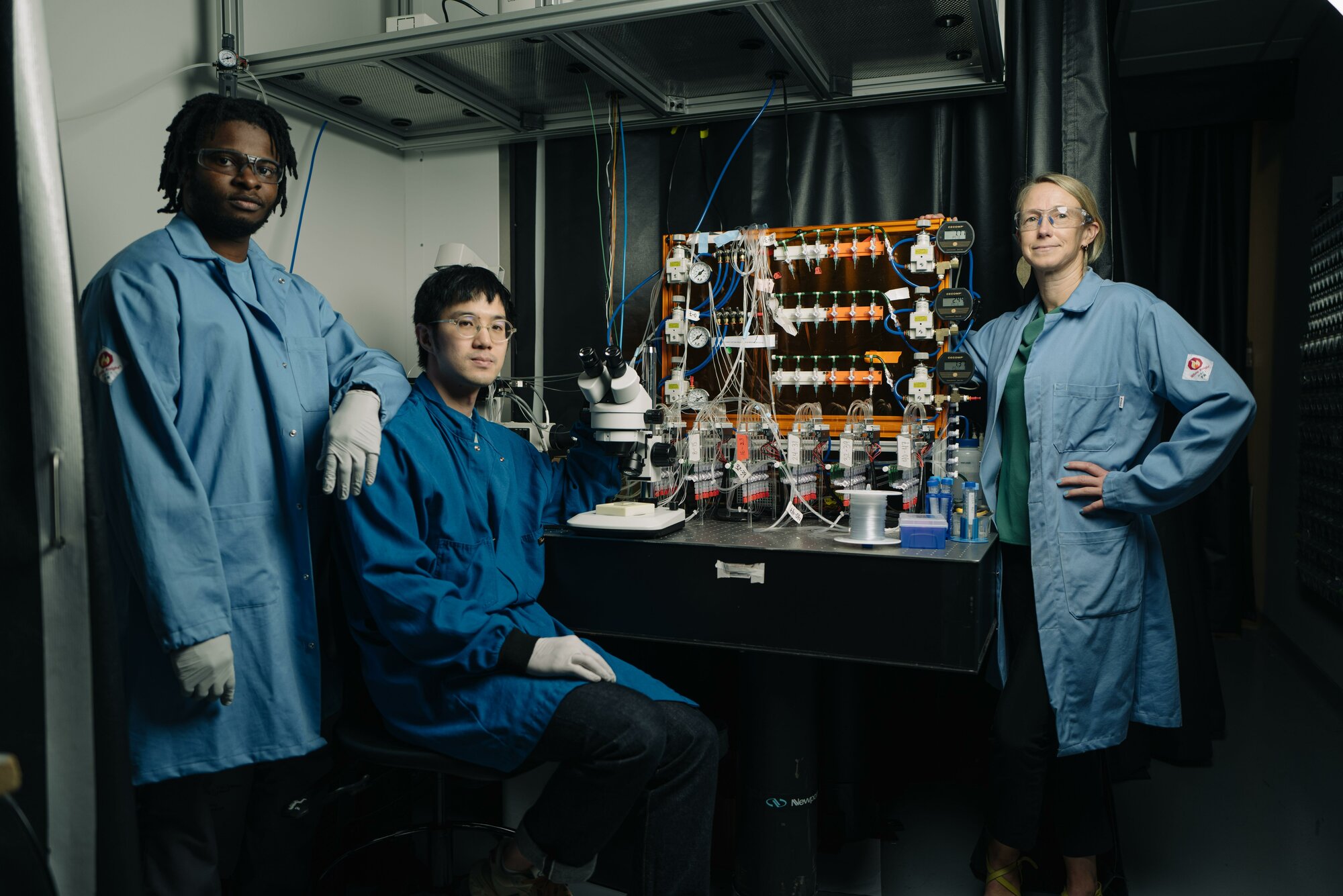

Fordyce is also developing platforms that multiply how many tests researchers can run at a time – by shrinking down laboratory equipment. “Instead of using a big beaker or a flask, we make these microfluidic devices that have 1,800 one-nanoliter chambers, a millionth of a milliliter,” explains Fordyce, who is also an institute scholar of Sarafan ChEM-H. “We’ll usually make 1,000 or 2,000 different protein variants in parallel, and systematically test how each one of those variations impacts the function.”

These new platforms are allowing researchers to answer some big questions about life. “The question that really interests me is: How do these tiny components self-assemble without any guiding hand into cells that are 1,000 times bigger than they are?” says Dunn.

In the past, this may have been just an interesting thought, but today Dunn can actually test it. In one project, he attaches microscopic beads to heart muscle proteins. Then, he uses a laser beam to manipulate the beads to see how the proteins respond. His research reveals how proteins sense their surroundings via tugging forces, providing a new molecular-level lens to understand cardiac health.

Modifying proteins with beneficial mutations

In addition to observing existing proteins, some researchers want to identify protein mutations that optimize certain functions. Often, they do this by starting with a protein that already does some of what they’re interested in, and then tweak its amino acid chain to adjust that activity up or down.

Unfortunately, sifting randomly through possible protein tweaks can be like finding a needle in a haystack, says bioengineering professor Jennifer Cochran. Producing and testing thousands or even millions of variants is expensive and cumbersome. Cochran and her colleagues have developed assays that can rapidly comb through millions of proteins, narrowing down the ones that are the most promising. For example, these screens can use a molecular bait that draws out the proteins with amino acids that confer altered activity to pinpoint which proteins warrant further study.

Another approach is a computer model that uses machine learning to narrow down beneficial protein mutations. Stanford researchers trained the model using fill-in-the-blank games, explains Hie. His team would leave some spaces blank on known protein sequences and ask the model to input the correct amino acid. With millions of repetitions in practice, the model grew better and better at predicting correct answers. In a recent paper in Science, they reported that the model was better at proposing beneficial mutations to an antibody than random guessing. “Instead of testing a million mutations on each round of evolution,” he said, “we just tested 10 to 30.”

Protein potential to improve health and the environment

Rapidly identifying beneficial mutations may bring a boost to the protein therapeutics industry. Proteins can carry drugs to a specific location or act as the drugs themselves by binding to a target cell and changing its activity. “If I can gum up this protein or if I can goose up the activity of this protein by various engineering tricks, I can provide a clinically meaningful benefit to the patient,” says Khosla. One branch of his research is focused on gumming up a protein that’s responsible for the immune reaction to gluten in celiac disease.

In Hie’s work, the team focused on a discontinued SARS-CoV-2 antibody treatment. While the treatment had been effective in patients for a couple months, the virus soon evolved enough to evade it, leading the FDA to pull the treatment. In the paper, the team identified antibody mutations that could bind to more recent virus strains, opening the door to making antibody treatments more responsive to shifting pathogen targets.

Proteins are also of interest in oncology. Cochran has engineered proteins that tightly bind to molecules that signal tumors to grow, and thereby block their signaling. Engineered proteins developed by Cochran and her team have also tagged tumors as an invader, leading the immune system to attack the cancer. She found these engineered proteins killed cancer cells and inhibited tumor progression in laboratory mice, and the treatment is now advancing toward clinical development in humans.

Another researcher, Elizabeth Sattely, draws inspiration from nature’s chemists. Sattely, associate professor of chemical engineering, studies how plants use enzyme “factories” to create an array of chemicals. “Those enzyme catalysts can do reactions that are really difficult for humans to do using chemical synthesis.” By determining the enzymes responsible for producing a target chemical, she hopes to be able to reproduce that process in a more economically viable way, such as by genetically modifying yeast cells with those enzymes. In one study in Science, she demonstrated that a chemotherapy drug found in a Himalayan plant could be produced in a widely available plant by encoding it with genes for that enzyme factory.

Protein research also has applications beyond medicine. Engineered enzymes could be used to degrade plastic, addressing waste problems such as the Pacific garbage patch, says Fordyce. Enzymes can also be used to synthesize chemicals, reducing energy-intensive manufacturing, and biofuels, bringing us closer to a carbon-neutral future.

As research and commercial interest grow, the possibilities for proteins are practically endless. “This is a really exciting time for this field,” says Fordyce.

For more information

Chaitan Khosla is a professor of chemistry in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

This story was originally published by the Stanford School of Engineering.