Early morning calls, champagne, a deluge of invites, hanging out with Swedish royalty.

In anticipation of this year’s Nobel Prizes, Stanford Report spoke with three of Stanford’s Nobel laureates to learn more about what it’s like to win the prestigious prize.

In 2022, Stanford chemist and the Baker Family Director of Sarafan ChEM-H Carolyn Bertozzi was awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry with Morten Meldal and K. Barry Sharpless, PhD ’68, for the development of click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry.

William F. Sharpe, the STANCO 25 Professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Emeritus, won the prize for economic sciences in 1990 with Harry M. Markowitz and Merton H. Miller for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics.

Carl Wieman, the Cheriton Professor in the School of Engineering, Emeritus, and professor emeritus of physics and of education, won the 2001 Nobel Prize in physics with Wolfgang Ketterle and Eric A. Cornell, BS ’85, for creating Bose-Einstein condensation using laser cooling and evaporation techniques.

Here, Bertozzi, Sharpe, and Wieman share their reflections on receiving the award: Answers have been edited for clarity.

Carl Wieman shifted his focus to education following his Nobel win in physics. | L.A. Cicero

What happened when you won?

Bertozzi: The first thing I thought was, “Oh, I’m so happy that my dad is alive to see this!” He was 91 at the time, and he answered my call at 2 a.m. He really needed that because this happened almost a year after my mother died, and he had moved to California after living his whole life in Massachusetts. Even two years later, that’s all he talks about. If he meets a new person who hasn’t already heard this a million times, he mentions the Nobel. He was a physics professor, and he’s very proud. Another cool thing was my former students and postdocs organized a Zoom celebration the next day, and around 120 people showed up from different time zones. We toasted champagne, and they roasted me. It’s a tradition in my group that when people leave, we always do a roast with the top 10 reasons why they should leave. They did that for me with the top 10 reasons why I should not have won the Nobel Prize – all the lame reasons about me that should have made me ineligible from day one. It was hilarious.

Sharpe: My wife, Kathy, and I were at a conference in Tucson, Arizona, and a call came in around 3 a.m. from a man with an accent. I thought, nobody knows I’m here except people at the conference. The caller obviously had tons of experience waking people up, and he carefully explained it was about the Nobel Prize. As it became clear this was real, as my wife tells it, I was bouncing up and down on the bed. We got breakfast and sat on our little deck as the sun rose over the hills behind Tucson. Then we went downstairs to let them know we weren’t going to be at the conference. Champagne arrived, the hotel gave us two extra rooms, and all hell broke loose with me on one phone and Kathy on the other. Stanford arranged for a press conference at the hotel and then we had two days of peace and quiet driving back before it got wild again.

Wieman: I was at home and woken up in the middle of the night. I was supposed to be teaching an introductory physics course that morning, and the public relations people at University of Colorado Boulder said, “Oh, no, you can’t teach. You have a press conference.” I had to explain to them that no, first I owed it to my students, and second, from a public relations point of view, having me teach first is really good public relations, and of course I was right. That got lots of attention and a favorable response. There were floods of congratulatory notes so I was trying to respond to those. This is gonna sound awfully arrogant, but it wasn’t a tremendous surprise because the work we did got so much attention that everybody was talking about it. We had received sort of an unusual amount of attention because it just captured a lot of people’s imaginations in physics.

Carolyn Bertozzi receives her Nobel Prize from H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden at Konserthuset Stockholm on Dec. 10, 2022. | Nanaka Adachi/Nobel Prize Outreach

What was it like in Stockholm?

Bertozzi: That whole two-week extravaganza was something you’ve never experienced in any other way. First of all, you’re entertained by the Royal Swedish Academy, the Nobel Committee, and the royal family of Sweden. The medal is given to you by the king of Sweden, and it’s a celebration that is very meaningful and historic for them. The Nobel Museum is there, which now has things from me as part of a display, as from every laureate. It’s like the Oscars with a red carpet and reporters interviewing people as they walk down, with a gown, accompanied by royalty. It’s an experience that people normally don’t have. It’s like the experience of Hollywood superstars, but Swedish style. A person is lucky to have that in their memory bank.

Sharpe: The whole thing is fabulous and exhausting. We gave talks at various places in Stockholm and other parts of the country. We had cars with a chauffeur, and I had a handler. It’s the first time I understood how top politicians or business people can function because they take care of everything. It’s really astounding how much productivity you can fake at least if you have a really good assistant. People wave at you while you walk down the sidewalk, and it was interesting to meet people from different fields. One of the winners was from Mexico, Octavio Paz, for literature, and he had a commanding presence and this gorgeous movie star wife. Whenever we were all in a room, the press would go to him of course because you can write a story about someone in literature winning the prize – but good luck writing about someone in economics!

Wieman: The Swedes make a really big deal out of it. You spend a week with all these parties, fancy dinners, talks, meetings, concerts, and so on. I think partly it’s because that time of year in Sweden is so dark and gloomy, they want to sort of liven things up. It was nice to have that. I remember meeting the queen of the Netherlands and the president and high-level people like that, but I have to admit, I don’t get too impressed by that, so I don’t remember them all that well.

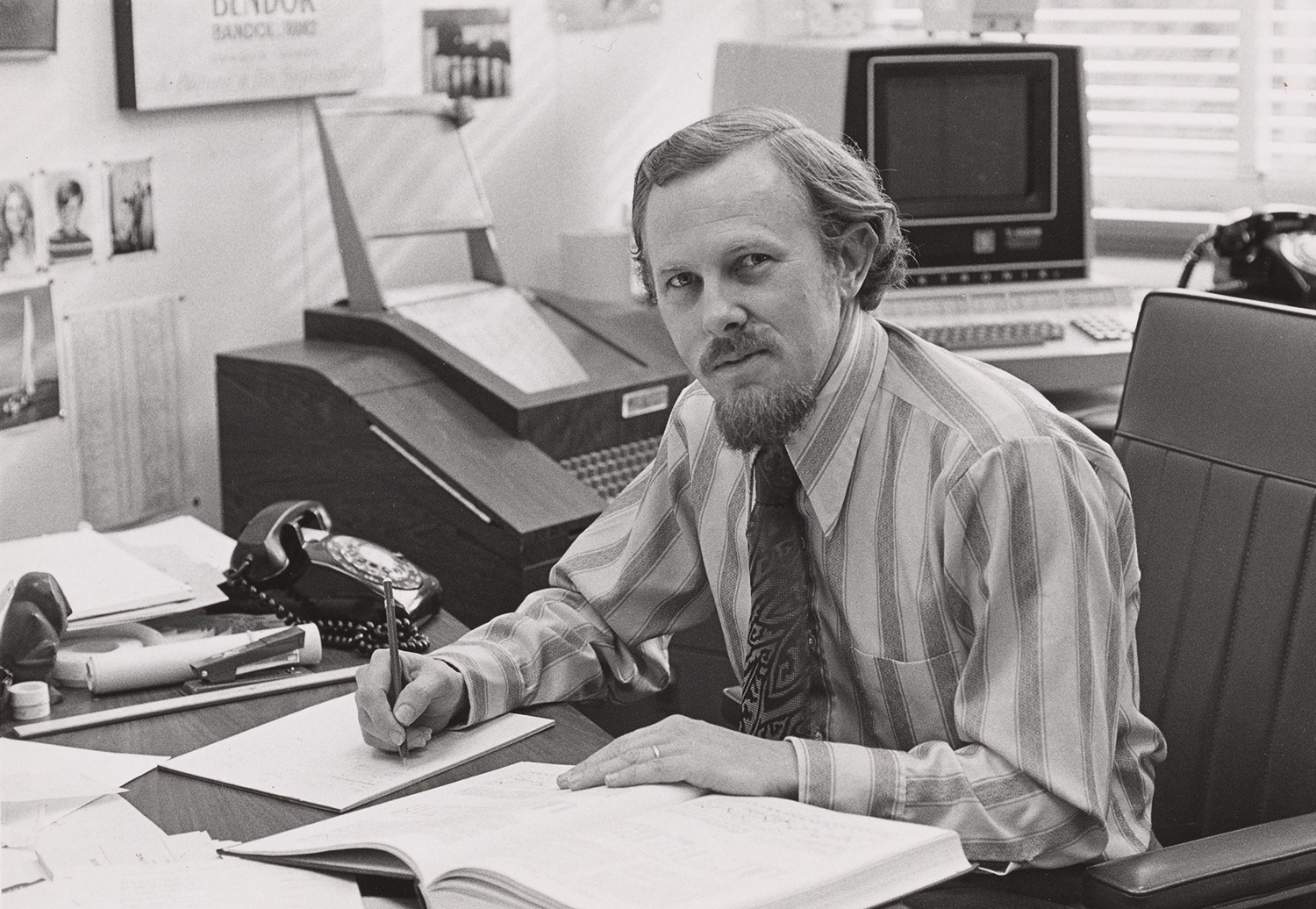

William F. Sharpe joined the Stanford faculty in 1970. | Stanford University

How did winning impact your life?

Bertozzi: It definitely was a lot of attention and invitations to either speak at a conference, visit a department, be on a committee, be on a board, or sign an open letter to the government about something that you’re not credentialed to opine on. I have colleagues here with Nobel Prizes, like W.E. Moerner, who helped me navigate what things to ignore and which to take seriously. The first year, there’s a lot of invitations, expectations, demands, and disappointments because you have to say no to most of it. I was teaching a biochemistry class that started winter quarter so I couldn’t travel that much. Time doesn’t expand just because you won a Nobel Prize. You also have an opportunity to try and reflect some of the spotlight on the people around you. I get to cast that light all over ChEM-H. Also, I did not get a parking spot, which is one thing Berkeley does, and there, it can change your life. I still ride my scooter to work.

Sharpe: It’s a wonderful experience, and one hopes that it’s a recognition that you’ve actually done useful things. The three of us – Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller, and myself – were all in the early days of trying to bring rigor, models, mathematics, and empirical analysis to the field of investments. So in many ways being awarded the prize was a recognition of the academic legitimacy of the field of financial economics, which was very gratifying.

Wieman: It really opened up new opportunities in the long term and gets more people to listen to you. I started the PhET Interactive Simulations project with the Nobel Prize money, making these interactive simulations for teaching science. That’s now one of the biggest free educational resources and is used a million times a day by kids all over the world. Me having a Nobel Prize also attracted some support for it. Several years after I won the prize, I also switched my area of focus to education and started this very large-scale project changing how teaching is done at the whole university. Since I had the prize and the stature, I found that I could make a more important impact there than I could continue doing in physics.

Stanford Nobel laureates

As of 2023, Stanford has three dozen Nobel laureates, 20 of whom are still alive. Some laureates with a significant Stanford connection are not included in the list since they are not on the faculty, and the university doesn’t list winners with a more fleeting connection, such as John Steinbeck, who won the 1962 Nobel Prize in literature but dropped out of Stanford twice.

Anything that surprised you?

Bertozzi: When I go to conferences, young folks want to take selfies with me and sometimes even want an autograph. It’s more intense when you’re either in Europe or in Asia, where a Nobel laureate has a certain celebrity status. When I give a lecture, there’s a line afterward of people who want to have a selfie and an autograph. So that’s a little strange, but if a young person feels like a scientist is a celebrity – as opposed to some other character who might not have really done much good for the world – in that sense, it’s positive. Scientists are heroes with or without Nobel Prizes, and a lot of them are public servants.

Sharpe: You get people who want to drop your name or have you sign on so you’re an adviser to X and Y, but your colleagues know you’re the same person you were beforehand. What’s interesting is that about half of people will say you won the Nobel Peace Prize and you have to set them straight.

Advice for others who win?

Bertozzi: I was advised to be wary of invitations that look weird, such as for events with people who just want to rub elbows with Nobel laureates, or invitations where there’s financial compensation that seems out of proportion. Also just say no to as much as you can to guard your time. You just have to be very disciplined about declining things and that’s hard. I always feel bad saying no to something, and especially if students are involved. You kind of have to because you cannot be all things to all people.

Wieman: Remember to stay humble, in that people will ask you as an expert on all kinds of things that you don’t know very much about. It is awfully hard when somebody looks to you for expert advice to remember to control yourself and say, “No, I don’t know.”

For more information

Bertozzi is the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences and professor, by courtesy, of chemical systems biology and of radiology in the School of Medicine.