In his autobiography, Open, tennis great Andre Agassi writes candidly about his feelings towards his extraordinary career. He shares that despite his professional success, he grappled with an inner conflict.

“A contradiction I came to terms with was being really good at something I hated,” he said Tuesday at Memorial Auditorium before a crowd of mostly new first-year and transfer students.

“I spent most of my life not knowing who I was – a good chunk of my life [with] people telling me who I was,” he said, adding that writing a book helped him, “figure out how to make sense of so many contradictions that I had in my heart and mind.”

Open is one of this year’s selections for the Three Books program. It is assigned to the fall COLLEGE course Why College? Your Education and the Good Life, which challenges students to reflect on the place and purpose of college in their lives, what kind of person they want to be, and the life they want to live.

In his introduction, President Jon Levin remarked on Agassi’s incredible career and compelling turn as a best-selling memoirist. “Once in a while someone writes a book that just completely makes you change everything you thought of that person,” Levin said. “Andre wrote a book like that.”

The event included a discussion with Agassi, moderated by Professor Robert Harrison, the Rosina Pierotti Professor of Italian Literature, Emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences, followed by a question-and-answer session with students.

Motivating factors

Agassi is one of the world’s most successful tennis players. He turned pro at age 16, gaining attention for his unconventional outfits, which consisted of denim, colorful shirts and compression shorts, and a mullet. He’s won 60 men’s singles titles, including eight Grand Slam singles championships, and an Olympic gold medal. He was often ranked number one in the world during his professional career, which spanned 21 years, and in 2011 was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

However, he said, “Tennis was never my choice. It was my father’s choice.”

“I was raised to believe that my identity was going to come through my success and performance as a tennis player,” he added.

Agassi said his father created an environment in which Agassi feared failure – and fear became his motivation. At 13, he was sent to a tennis academy in Florida where he said he was defined by his performance. Although he grew to hate it, he said his only way out was to improve. “The only way out of academy, the only way of taking ownership of my life at all was to succeed,” he said.

His rebellion – masked as winning – continued on the world stage, but the disconnect remained. He had to make sense of things that felt good – like winning trophies and money – but that didn’t define him, all the while not knowing how to define himself.

“I didn’t know who I was,” he conceded.

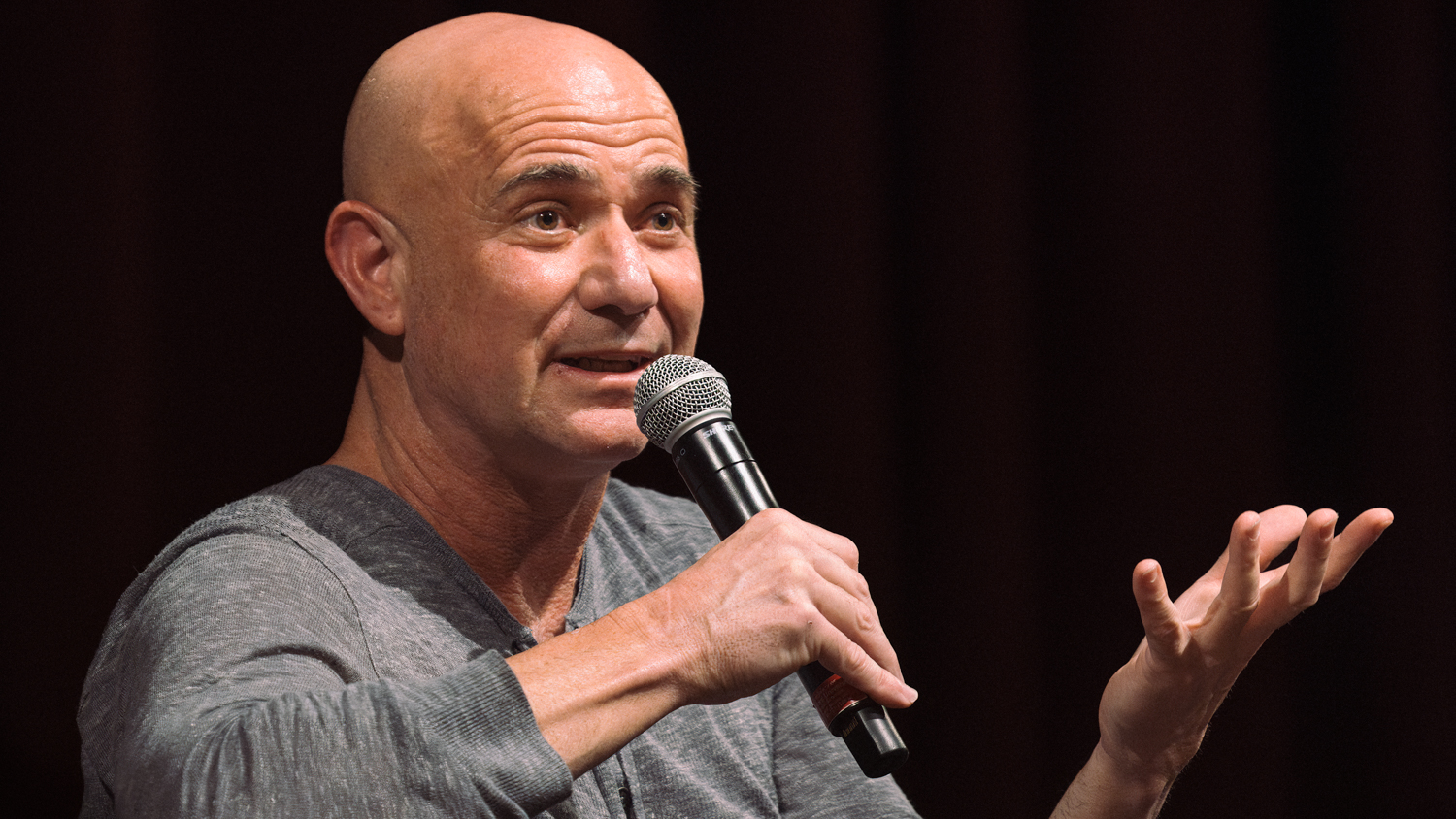

Andre Agassi speaking at Memorial Auditorium. | Andrew Brodhead

A hero’s journey

Roughly a decade into his professional tennis career, Agassi began to falter, and, in 1997, his rank plummeted to 141 in the world. At his lowest point, he gave himself permission to quit, but “In true fashion to my process, I rebelled against myself. I said I didn’t deserve to quit,” he recalled.

The following year Agassi made a stunning comeback, climbing back up the rankings to become the world’s sixth-best player – a record turnaround.

He said everyone is on their own “hero’s journey” and that his journey forced him to learn that chasing perfection was futile. “Perfectionism is a destination you never really get to,” he said.

In Open, he recalls how helping a friend put their kids through school helped him redefine excellence and find purpose outside of tennis. “This is the only perfection there is, the perfection of helping others. This is the only thing we can do that has any lasting value or meaning. This is why we’re here, to help each other feel safe.”

He established the Andre Agassi Charitable Foundation, through which he’s donated millions to projects like the Agassi College Preparatory Academy and the Agassi Boys and Girls Club in his hometown of Las Vegas.

Practicing gratitude

During the Q&A portion of the event, Agassi said that while he had many moments of happiness throughout his career, he often lacked genuine gratitude. He reminded students that there’s more to be thankful for in life than just accolades.

“It’s good to be grateful in all things. Not for things,” he said.

A student asked Agassi who he thought was the tennis GOAT, or greatest of all time. “You absolutely cannot deny the numbers and the accomplishments and the records that Novak [Djokovic] has put on the board,” he responded.

When asked if his struggles – with his father, and to define himself on his own terms, and forcing himself to play a sport he hated – were worth it given all the good it led to, like his charitable work, he said “absolutely” it was.

Open, which was published in 2009, became a #1 New York Times best-seller. When asked about his decision to write it, Agassi said that vulnerability is “essential to growth,” and that even years later, he’s still evolving.

“The book didn’t change my life. I’m continually forming,” he said. “It was a necessary part of my growth, but my growth has continued.”