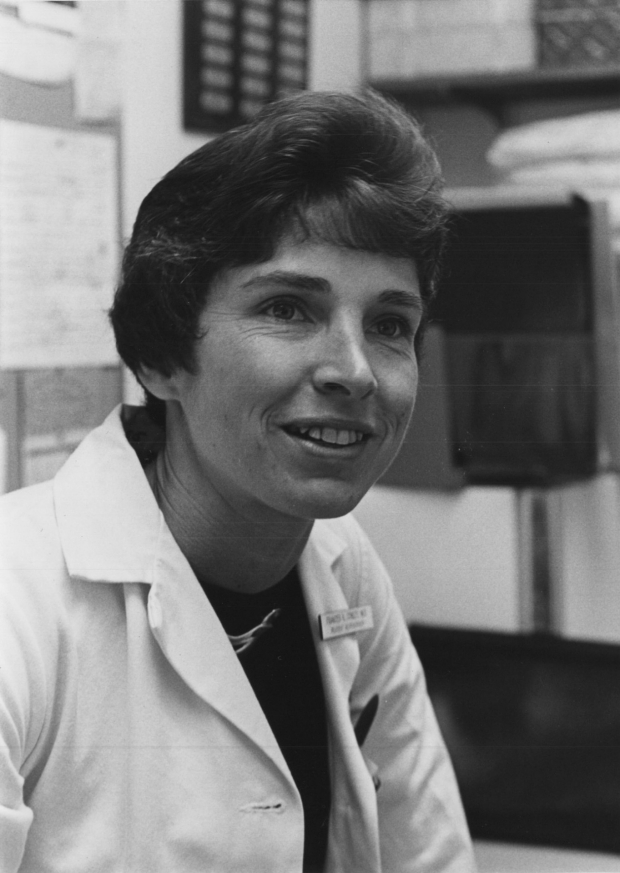

Frances Krauskopf Conley, MD, a trailblazing neurosurgeon at Stanford Medicine, who, in 1982, became the country’s first female tenured professor in neurosurgery and later made national headlines for speaking out against sexism in medicine, died Aug. 5, 2024, in Sea Ranch, California, after a long illness. She was 83.

She was a highly skilled and innovative surgeon, specializing in spinal surgeries and carotid artery blockages; an accomplished researcher, studying how the immune system might be harnessed to fight brain tumors; and a compelling educator whose legacy continues to inspire new generations entering the profession. She also served as chief of staff at the Palo Alto Veterans Administration Health System from 1998 to 2000.

“Dr. Conley was an outstanding neurosurgeon who was driven to pursue both excellence and equality in her work,” said Lloyd Minor, MD, dean of the Stanford School of Medicine and vice president of medical affairs at Stanford University. “Her fight for her own dignity and the dignity of others facing discrimination left an indelible impact on the Stanford Medicine community and beyond.”

Conley possessed the confidence and fearlessness not uncommon among surgeons in a highly competitive field, but she was singular among her peers in having to apply those qualities to navigate ingrained prejudices throughout her career.

“She was very much a fighter, and she probably needed to be a fighter,” said John Adler, MD, professor emeritus of neurosurgery, who became friends with Conley after she recruited him to Stanford in 1987. “Being one of the first women in the specialty, she faced more skepticism than most.”

As a medical student in the early 1990s and later as a neurosurgery resident, Odette Harris, MD, encountered Conley in operating rooms and in lecture halls.

“Her visibility, her accomplishments blazed a path for us all,” said Harris, the Paralyzed Veterans of America Professor in Spinal Cord Injury Medicine and one of the first Black female professors of neurosurgery in the country. “We could look to her. There was nobody else in the country that had a woman neurosurgeon on faculty.”

Harris remembers attending a neuroscience lecture in which Conley talked about how high heels contributed to back pain and posture problems, yet women had tolerated wearing shoes designed by men who would never wear them. “As a back surgeon, she was on a campaign against them,” Harris said. “She actually wore trainers.”

“She stood for something, and she was unapologetic about it, regardless of how popular or unpopular it was.”

After Harris graduated from medical school and started her career, once in a while she would receive an unsolicited letter of encouragement from Conley. “She went out of her way to reach out to me and to provide me with what I call stealth support,” Harris said. “She always wrote at a time when I felt like the support was powerful. The fact that she celebrated in my accomplishments was incredibly meaningful to me.”

Joining an exclusive group

Frances Krauskopf was born Aug. 12, 1940, in Palo Alto, California. Her father was a professor of geochemistry at Stanford University. Her mother raised four kids, then returned to work as a teacher and counselor. Her parents encouraged her career aspirations, but she recalled that “even in my wonderful, egalitarian, liberal, academic family,” her brother was given a life insurance policy for his 16th birthday, whereas she and her sisters were given sewing machines for theirs.

She attended Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania for two years before transferring to Stanford University. She applied to the Stanford School of Medicine after her junior year and began medical school in 1961, part of a class with an unusually high number of women for the time – 12 out of 60. She recalled that nearly everything they were taught, from physiology to biochemistry, was “from the ‘normal’ perspective of the 70-kilogram man, the paradigm upon which all traditional medical education was based.” Women’s health focused almost entirely on their reproductive function.

Between her first and second years of medical school, she met Philip Conley, a tall, handsome California Institute of Technology graduate with an MBA from Harvard. They were both gifted athletes, she as a runner, and he in javelin — he represented the United States at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia. They were married the following summer.

In 1966, she became the first female surgical resident at Stanford University Hospital. “As with acceptance to medical school, I was so happy to just be included I would have walked on my hands for the entire year if that was what it took to belong and be part of this exclusive group,” she wrote.

Frances Conley wrote a book about her experiences as a woman in a male-dominated field.

Stanford Medicine

After initially considering plastic surgery, the most acceptable surgical specialty for women at the time, Conley decided on neurosurgery, enthralled by the ability to turn around patients’ lives. “A paralyzed patient walks, a mute stroke patient talks, a tumor patient borrows extra time. I knew then this was what I wanted to do with my life.”

In 1975, she joined the faculty as an assistant professor and chief of neurosurgery at the Palo Alto VA hospital. She also established a research lab at the VA, focusing on the development of an immunotherapy for brain tumors using rodent models.

In the operating room, she brought new procedures to neurosurgery – including lumbar spine fusion, which connected vertebrae to ease pain and had been primarily performed by orthopaedic surgeons; and carotid endarterectomies, which cleared plaque from arteries supplying blood to the brain. Both treated conditions were prevalent among patients who were veterans.

“She was an excellent neurosurgeon and took outstanding care of her patients,” said Lawrence Shuer, MD, professor of neurosurgery who served as acting chair of the department from 1992 to 1995. “I think her patients were appreciative of the innovative care she brought to them.”

Changing the world

In 1982, she became the first woman in America to be awarded tenure in neurosurgery. (That same year, she was among the women featured in a Time magazine article titled, “The New Ideal of Beauty,” including a photo of her holding a javelin.)

She took a sabbatical year in 1985 to complete a master’s in management science at the Stanford Graduate School of Business where she studied cost-benefit analyses, organizational behavior, and power dynamics.

“Her aspiration was that she really wanted to change the world,” said Ron Sann, her nephew-in-law. “And she had a belief that she could do anything that a guy could do, which today may not be a revolutionary concept, but at the time, it was considered an avant-garde perspective.”

In 1991, Conley made a bold stand against a colleague’s promotion to chair of the Neurosurgery Department, voicing her concerns about equity and standards of leadership conduct. Her public protest sparked a national conversation about sexism in academic medicine. After the Stanford School of Medicine’s dean committed to addressing the issues she raised, Conley decided to stay on as tenured faculty. Her protest inspired many to advocate for a more equitable future in medicine.

Conley was invited to public speaking engagements around the country, including three commencement addresses. It seemed that at every medical school she visited, students and faculty told her stories of unequal and abusive treatment toward women. She also heard from nurses and clerical staff who risked their more vulnerable careers to tell their stories.

In 1998, Conley published a book, Walking Out on the Boys, chronicling the episode from her perspective.

“She felt that this was an important thing for her to do,” Adler said, “that if someone didn’t wage this fight, young women neurosurgeons would be at a disadvantage in years to come.”

Winning the race

Her drive and conviction extended beyond medicine.

In 1971, the first year that women were allowed to enter the 7-mile Bay to Breakers race in San Francisco, Conley was the first woman to cross the finish line, where a reporter asked if she was married. The next day, the newspaper announced that a “Palo Alto housewife” had won the women’s race. Few people knew that this was technically her second win — several years prior she had entered the race as “Francis” and finished the race in an overcoat.

“I think women’s rights as a whole was the metric she was really interested in,” Sann said.

In 1997, she was appointed acting chief of staff at the Palo Alto VA Health Care System and elected chair of the university’s faculty senate. She served on the editorial boards of the journals Neurosurgery and American Family Physician, and as chair of public relations for both the Congress of Neurological Surgeons and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons.

Conley retired from Stanford Medicine in 2000. She, her husband, and their beloved dogs moved to Sea Ranch, a tranquil coastal community in Sonoma County. They ran together, and she volunteered at a local clinic.

Though they did not have children, the Conleys built a family among the Stanford community. They funded scholarships and took many Stanford University undergraduates, usually student-athletes, under their wing.

Conley is survived by her sisters, Karen Hyde of Belvedere, California, and Marion Forester of Oceanside, California; her brother, Karl Krauskopf of Jacksonville, Oregon; and eight nieces and nephews. Her husband died in 2014.

For more information

This story was originally published by Stanford Medicine.