Kristy Red-Horse says she “eats, breathes, and lives” her work – not that it really feels like work to her. While it sounds (and is) complicated to study how blood vessels develop and respond to injury, it fits neatly into what she loves about science and what questions in medicine she wants to answer. Red-Horse is a professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences and one of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigators at Stanford, but there were times when such achievements seemed out of reach.

Red-Horse talks about the many people who inspired and supported her, the way her work translates from the lab to clinical medicine, and how failure and success played a part in getting her to where she is today.

“I think the ability to pick up and try something new is pretty important. I wasn’t afraid to move, I changed labs a couple times, and it was the best thing I ever did – that’s a little secret to my success,” said Red-Horse. “Everyone shines in different ways in different environments. You just have to find your place.”

Here’s the who, what, how, and why of Professor Kristy Red-Horse:

Who (are you)?

I’m Kristy Red-Horse, I’m a professor of biology and affiliate faculty for the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, as well as an HHMI investigator.

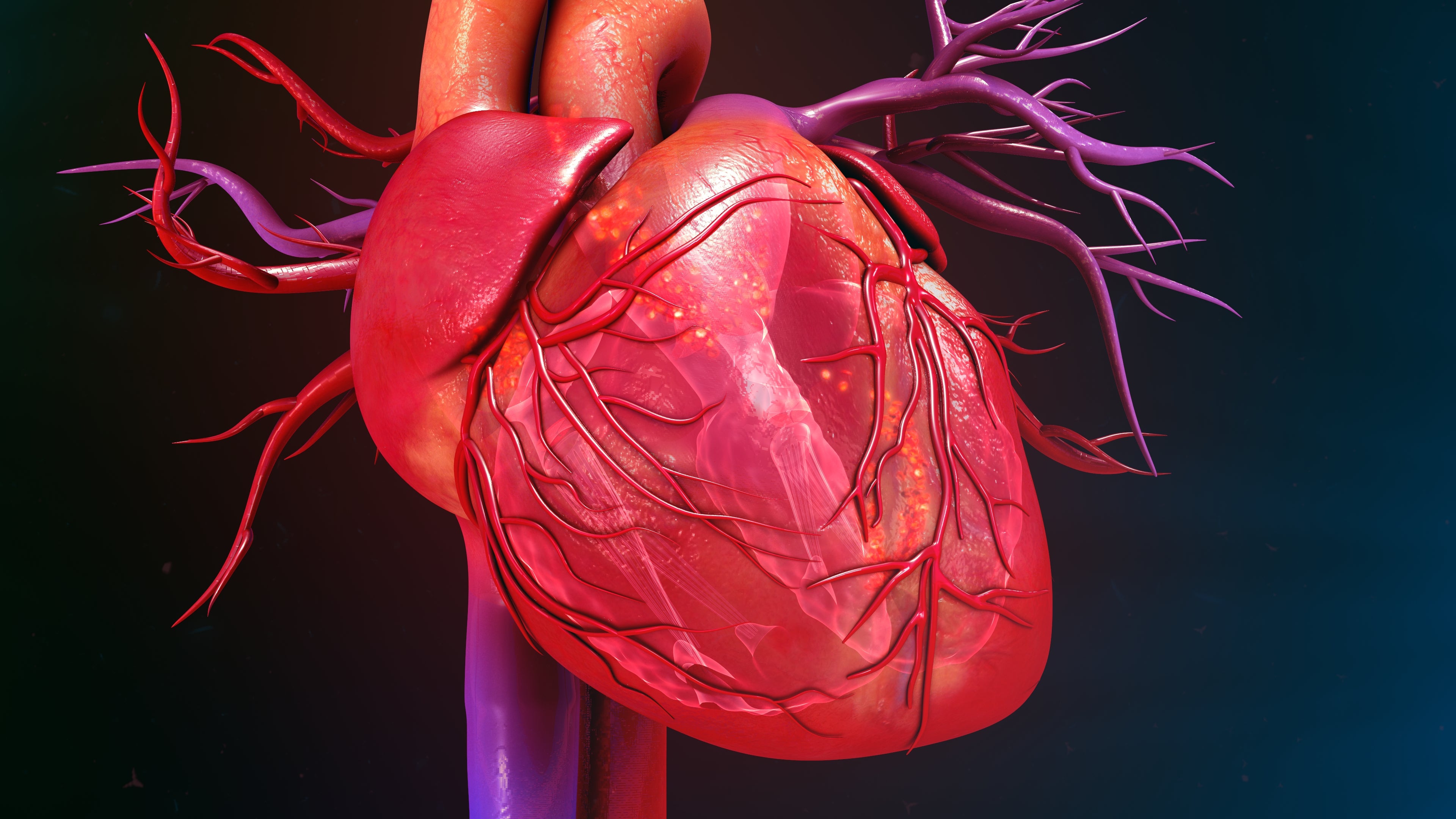

We research how the heart blood vessels – the ones that bring blood flow and oxygenation to the heart muscle – develop and how they respond to an injury, such as a myocardial infarction or a heart attack. One reason we’re so interested in development is because the pathways that are responsible for blood vessel development are the same ones that you can use to encourage redevelopment when a blockage happens.

Heart disease is the number one killer in the United States, so it’s important to study these kinds of things to enable new treatments that can be less invasive than, say, open heart surgery.

What (do you do at Stanford)?

Currently, we focus on using innovative strategies for our findings, especially using natural variation in species to investigate possibilities for making human hearts more reparative. For example, we’re currently studying guinea pigs because they can’t get heart attacks from blockages in their coronary artery. They instead develop these natural bypass arteries. We’re researching this so we can encourage bypasses to grow in a heart disease scenario in humans – potentially by triggering certain molecular pathways using drugs. Some humans are able to grow these collateral bypass arteries, but we just don’t understand all the reasons why yet.

Collateral bypass arteries are a really interesting type of vessel and a rare artery type. Usually, arteries branch out into capillaries like trees, smaller and smaller. But these are like the rungs of a ladder, and they connect to each other. So, how those form is really fascinating from a developmental biology perspective.

How (did you get here)?

I had a high school teacher named Mrs. Parnell who got me interested in biology because her class was so fascinating. And then I went to undergrad at the University of Arkansas and did microbiology and really loved immunology. The faculty member teaching immunology asked if I wanted to do research in the lab – I don’t know if you know Arkansas much, but it is the land where Tyson chicken is, so for my first project, I studied poultry immunology.

I knew I liked research, but I didn’t quite know what to do. I wanted to move someplace different and exciting, so I did a master’s at San Francisco State University and was in a bacterial lab working on transcriptional regulation, which is how cells regulate the change from DNA to RNA. As soon as I cloned my first plasmid, I was like, “I love molecular biology,” and I didn’t look back from then. I just love the actual physical process of doing molecular biology experiments and looking in the microscope and all of those things.

Around that time, I saw Susan Fisher from UCSF give a talk about the placenta and its role as a vascular organ. I was captivated by both the research and her, as a possible mentor, so I joined her lab and stayed for a PhD, which is how I got into vasculature. Then I went on to do a postdoc, where Mark Krasnow encouraged me to look at a vascular bed that was clinically important. That is how I decided to dive deep into the blood vessels of the heart. I found out that at the time, scientists didn’t even know the origins of these blood vessels – there was so much to be discovered that it’s been keeping me busy for about 15 years now.

In the journey to get to where I’m at, one thing that was hard for me is that I am of Indigenous ancestry, but I didn’t meet my grandfather and get to know him until I was in my twenties. I really struggled with being a role model for other Native scientists – wondering if it was appropriate for me and “Do I really deserve this?” – since I didn’t grow up with that culture. It’s better now that I have the resources to give back and to support other Native scientists, and have gotten to discuss and learn about my culture with that part of my family.

Kristy Red-Horse in her office | Eli Ramos

Another thing that was difficult was that I did two postdocs. The first one, I felt like I was doing a lot of experiments, but nothing was really resonating or coming together – it just wasn’t a place for me to shine, and I realized that. Then I moved to Mark’s lab here for my second postdoc. When that happened, I was devastated, absolutely devastated, because I thought I had ruined my chance to be an academic lab head. Because in my mind, you just don’t do two postdocs. So, I thought I’d failed.

But after that period, I didn’t care anymore about being brilliant or looking good, so I just enjoyed myself. It was a very sad moment, but it taught me to not worry all the time about how you look or how you work. Every time something really, really hard happens, I think maybe it’s going to be for the best, because I remember back to that time.

Why (do you do what you do)?

I mean, I’m really steeped in this work. I get so much joy out of the discovery process and the human story of how discovery happens. I love going to a seminar and hearing somebody’s big discovery and how they stumbled across it. And of course, I just love the process of doing experiments. I love the beauty when you do an experiment and you have all the controls, and it’s very clear what the answer is.

I also thought about becoming an artist and I enjoy visually beautiful images, which has spilled over into my work. I’ve gravitated more toward experiments where I can see visually beautiful representations of the science.

The clinical translational side is another reason why I work on this research. Early on when I started my lab, I was giving a talk and a surgeon came up to me and said, “Those are really beautiful images you presented, but I think you should be studying these other really cool vessels called collateral arteries.” So, while I was really good at figuring out the biology, we needed a hint from clinicians to steer us toward some important biology – and we still work with clinicians to understand what’s going on.

Now, we’re working with Tim Assimes and colleagues, who are associated with the Million Veteran Program. This program collects data from this inside-the-body imaging procedure called an angiogram, which lets scientists look at the coronary tree and associate it with different genetic markers or DNA variants. And one of the top hits in their genome-wide association study was the exact same molecular pathway that we had figured out was responsible for making collateral arteries. Knowing that this pathway is shown to be important for directing coronary growth and development in humans gives you the energy to move forward. And we just got awarded a grant from the National Institutes of Health that will help us study why some humans make collateral arteries.

This has happened to me over and over where I get questions after I give a talk and I think, “Should I tell them I’m never going to be able to answer that?” but then, somehow, technology or a collaboration will happen and then I actually get to research it. So that’s extra special when that comes to fruition. And a lot of that comes from unrelenting persistence – which is how you can get yourself to shine.