Today, the Clayman Institute for Gender Research is a thriving hub at Stanford University committed to tackling big questions related to gender equality. It’s a place where experts, scholars, and students can work together to, for example, investigate how COVID-19 changed intimate partner violence in the home, or create an archive of all of the letters chronicling experiences of sexual harassment that were sent to prominent figures during the #MeToo movement.

But it wasn’t always this way.

When the institute’s founder, Myra Strober, arrived at Stanford as an assistant professor at the Graduate School of Business (GSB) in 1972, she could barely find a women’s restroom, let alone a place dedicated to the study of gender.

Little did she know that in a few years’ time, she would help establish one of the most preeminent centers dedicated to gender and feminist research.

Clayman’s origin story

In the early 1970s, Stanford was a different world: a man’s world. Strober, along with Francine Gordon, were the first two women professors at the GSB. The GSB student body was overwhelmingly composed of men, too: There were only five women students in the MBA graduating Class of 1972 – three of whom pointed out the disparity in a class presentation titled “What’s a nice girl like you doing in a place like this?”

“We all felt so out of place,” Strober recalled.

Myra Strober co-founded what is now known as the Clayman Institute for Gender Research in 1974. | Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research Records, Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections and University Archives

But times were changing.

The second-wave feminist and women’s movement was burgeoning – along with other social and civil rights causes – and Stanford, like other institutions across the country, was diversifying its faculty ranks. The same year Strober joined the GSB, there were other “firsts” across campus as well – for example, Stanford Law School had hired its first woman professor, Barbara Babcock.

A number of local papers ran stories about Stanford’s new hires – including one piece that noted how Strober, an economist, was doing research on women and work.

The story caught the eye of Stanford student Cynthia Davis (’74), who approached Strober with the idea of starting an academic research center dedicated to the study of women. While Strober liked the suggestion, she brushed Davis off, saying “assistant professors don’t start research centers.”

But a few months later, two other students – Beth Garfield (’74) and Susan Heck (PhD ’77) – also came up to Strober with the same idea. Strober repeated what she told Davis, but suggested they all meet to see how they might combine efforts.

Following Strober’s advice, Davis, Garfield, and Heck reached out to senior faculty members for their support, including Eleanor Maccoby, one of Stanford’s few fully tenured women professors, and James March, a well-connected faculty member with appointments in three of Stanford’s schools. They formed a task force, and eventually Strober found herself being asked the same question Davis, Garfield, and Heck posed to her some months prior: Could she help create such a center?

This time, Strober agreed – a decision that eventually resulted in what today is known as the Clayman Institute.

Doubling down

Strober saw the importance of having a space where scholars, whose research related to women in some way, could gather.

While Stanford had devoted space for women to meet, its purpose was social – not academic, which was what Davis, Garfield, Heck, and others yearned for.

At the time, Strober was increasingly feeling alienated as one of the only women on the faculty at the GSB, and at Stanford for that matter: Less than 6% of professors across the institution were women, and for the most part were either lecturers or untenured. While she was used to being in the minority – as a doctoral student at MIT, she was one of two women in a class of 30 – she said it felt different for her as a faculty member.

Her feelings of isolation only intensified after a seminar she was supposed to deliver to her colleagues about her research on the economics of childcare. She barely made it past the first opening sentences touting her discovery of its benefits – childcare helps not just working mothers but society as well – before she was interrupted.

“I never gave the seminar,” Strober said. “They just kept shouting what an outrageous idea this was.”

After the incident, some of Strober’s colleagues suggested that until she received tenure, she should turn her attention to something “less controversial” and more mainstream. But instead of backing down, Strober doubled down and continued researching and teaching courses on women and work.

She also worked tirelessly with scholars and students from across campus to create a space where researchers studying women and gender in society could discuss their findings. Through a grant from the Robert Sterling Clark Foundation, and later, the Ford Foundation, a lecture series was launched in 1973 .

For the first time at Stanford, scholars studying gender from different disciplines came together.

“There were many people around doing research on women,” Strober recalled, “but we didn’t know each other.”

As word spread about the lecture series, the audience grew. Crowds got so big Strober worried they were in breach of the fire code for having too many people in a room.

“It made us realize the vibrant work that was going on on campus,” Strober said.

Strober also found an ally in Jing Lyman, the wife of then Stanford President Richard Lyman, who brought with her not only unwavering support but also an extensive social network eager to create the research community Strober and others envisioned.

CROW began first as a series of lectures. | Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research Records, Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections and University Archives

Expanding a new field of inquiry

In 1974, the Stanford Center for Research on Women (CROW) was formally established to promote and support interdisciplinary research on women. The center eventually became the Institute for Research on Women and Gender (IRWG), and in 2010 was renamed the Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research.

When CROW launched, it was the first of two research centers in the country dedicated to the academic inquiry of women and gender. The other was at Wellesley, whose research center on women also launched that year.

Helping CROW grow were Davis, Garfield, and Heck, along with other faculty and scholars from across the university, along with Maccoby, Estelle Freedman, and others.

When Davis graduated from Stanford in 1974, she was hired to be CROW’s first administrator, a position she held for a number of years.

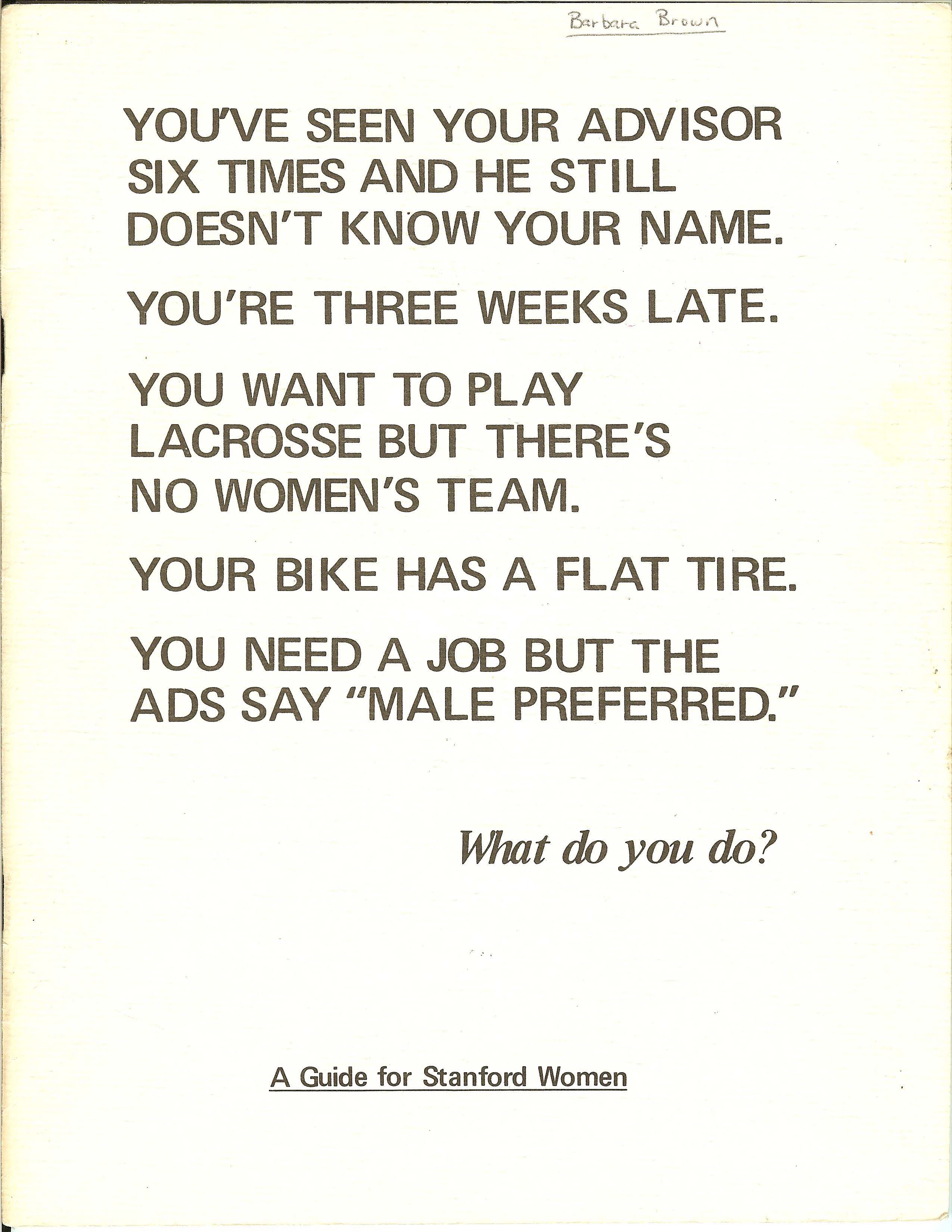

In 1974, Cynthia Davis co-authored “A Woman’s Guide to Stanford.” | Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research Records, Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections and University Archives

By 1976, Strober had secured additional funding to hire scholars to lead their own research projects. “Now we can have a real research center,” Strober wrote in her memoir. One of those appointments was literary scholar Marilyn Yalom, who later became CROW’s associate director and later, a director.

In 1980, the institute became home to the highly respected journal Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society.

During this period, members of CROW launched the Task Force on the Study of Women, an endeavor that led to the establishment of the Feminist Studies Program with historian Freedman as its first director in 1981.

The institute has also expanded to include a robust offering of fellowships for postdoctoral students, graduate students, and faculty, as well as varied and vibrant events, including the Jing Lyman Lecture Series, Clayman Conversations, and Attneave at Noon.

Helping scholars and their research flourish

Interdisciplinary research has always been foundational to the work of the institute.

Today, the institute is structured around a unique, intergenerational mentorship model.

Experienced mentors can offer valuable insights and guidance to younger mentees, while younger mentees can also offer fresh perspectives and new ideas of their own – which is vital, too, to the institute. Students, after all, helped create the Clayman Institute.

“Students are central to so much of what we do, from our dedication to intergenerational mentorship, to the topics of the events we convene, to meaningfully including students in all elements of our research,” said Alison Dahl Crossley, the institute’s executive director and a scholar of feminist movements.

Over five decades, the institute’s leadership has also continued to bring new perspectives to the academic inquiry of the role of gender in society. Under each new faculty director, the scholarly focus has also changed.

For example, under Laura Carstensen (1997-2001), the institute focused on understanding gendered differences on aging and longevity. When Londa Schiebinger led the institute (2004-2010), it shifted to the role of sex and gender in scientific research and development, and under Shelley Correll (2010-2019), it examined the persistence of gender inequities in academia and the professional workplace.

“No one social science or humanity can answer the questions that we have,” Strober said.

These focal areas blossomed into research hubs of their own that are thriving today: Carstensen launched the Stanford Center on Longevity, Schiebinger the Gendered Innovations in Science, Health & Medicine, Engineering, and Environment Project, and Correll the Stanford VMware Women’s Leadership Innovation Lab.

The Clayman Institute today

Today, the Clayman Institute can be found at the Carolyn Lewis Attneave House in the home that once belonged to Stanford’s first president, David Starr Jordan. The house has moved a number of times from where it was originally erected and now stands on Capistrano Way.

CROW’s offices at Serra House, which in 2019 was renamed Carolyn Lewis Attneave House. | Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research Records, Stanford University Libraries, Department of Special Collections and University Archives

Inside, portraits of the institute’s directors – some 11 trailblazers in total – line the staircase that leads to offices on the second floor, a reminder to students and scholars of the work these intrepid leaders did, forging not only a new path but innovating a new way to think about problems facing society.

For Adrian Daub, who became the Barbara D. Finberg Director of the institute in 2019, strengthening the scholarly structures his predecessors put in place is one of his goals.

“Taking over an institution of this caliber and history is a huge responsibility, and is about strengthening and building on the groundbreaking work done here for decades,” Daub said. “Part of that reflects that – when it comes to gender – the campus and the world are in some ways quite different in 2024 from when the institute was founded in 1974. But in other respects the problems persist, and modern scholarly approaches and young student researchers have to contend with challenges that are a lot older than them.”

Today, the Clayman Institute continues to host lectures and events, including bringing lawyer and scholar Anita Hill (right) to campus in 2024 for a conversation with institute director Adrian Daub (right). | Courtesy Clayman Institute

Hanging on the walls of the institute’s conference room are framed covers of Ms. Magazine, the feminist publication founded in the early 1970s by Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pittman Hughes, as well as a colorful bookcase showcasing some of the many publications the institute’s scholars have authored over the years. Stacks of the institute’s own magazine, upRising, are also scattered throughout Attneave House – all further reminders of the institute’s deep roots in activism and scholarship.

It’s a cozy and inviting space for scholars to convene and for alumni to return to – including Davis (who now goes by Russell) and Garfield, who both sit on the Clayman Institute’s advisory board, where they continue to advise on the institute’s direction. Heck has since passed away and a summer internship now exists in her honor. Their contributions were honored at an event in 2022.

Under Daub, the institute continues to build upon and expand its offerings. Building on the institute’s model of intergenerational mentorship, Daub hired a research associate to ensure undergraduate students are involved in every stage of the research process, not as assistants, but as collaborators. They are also on hand to help students navigate the emotions that arise when archiving and analyzing difficult materials detailing the persistent and pernicious violence toward women.

In 2020, Daub launched a podcast titled The Feminist Present with Laura Goode, associate director for student services for the Public Humanities Initiative, to engage new audiences with ideas and solutions to advance gender equality. In 2023, Daub and Moira Donegan, the columnist and Clayman’s writer-in-residence, created another podcast, In Bed with the Right, which invites a range of scholars and critics to analyze right-wing ideas about gender, sex, and sexuality and how those views shape contemporary society.

Strober remembers how, when the institute was first formed, a dean was worried that it was going to become a permanent institution.

“He asked me, did I agree that when – quote unquote – ‘this problem is solved’ we would sunset the center. I thought to myself, ‘This really is a softball question,’” Strober recalled. “I said, ‘Yes, I agree with you – as soon as this is over, we will sunset the center.’”

Affiliations and references:

The Clayman Institute is part of the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S). Carstensen is also a professor of psychology in H&S, where she is the Fairleigh S. Dickinson Jr. Professor in Public Policy. Correll is also the Michelle Mercer and Bruce Golden Family Professor in Women’s Leadership, director of Stanford VMware Women’s Leadership Innovation Lab, and a professor of sociology in H&S. Daub is also the J. E. Wallace Sterling Professor in the Humanities and a professor of comparative literature and German studies in H&S. Freedman is the Edgar E. Robinson Professor in U.S. History, Emerita, in H&S. Schiebinger is also the John L. Hinds Professor in the History of Science in H&S.

In addition to references cited, the following materials were also consulted for the writing of this piece: Myra Strober’s Sharing the Work: What My Family and Career Taught Me About Breaking Through and Holding the Door Open for Others (MIT Press, 2017); Clayman Institute’s History Overview.