If you walk around the Stanford campus today, the transformations that occurred under the leadership of the university’s fifth president, J. E. Wallace Sterling, are both seen and felt – from the physical campus itself to the vibrant and varied community of students, faculty, and staff.

“This book should not be considered the final, definitive biography of Wallace Sterling; it’s a roadmap or a travelogue that is meant to encourage further study into any one of the many topics this book explores or suggests,” co-author Roxanne Nilan said.

During a presidency that spanned nearly two decades – from 1949-1968 – Sterling made dramatic changes that have had a profound, long-lasting effect, all detailed in a new book, Stanford’s Wallace Sterling, Portrait of a Presidency 1949-1968 (Stanford Historical Society and the Society for the Promotion of Science and Scholarship; distributed by Stanford University Press, 2023), co-authored by Stanford’s former university archivist Roxanne L. Nilan, MA ’92, PhD ’99.

Sterling’s many accomplishments included moving the School of Medicine from San Francisco to the Stanford campus. He also oversaw the renovation and creation of new research facilities – including building the 2-mile long Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) as well as an additional 4 million square feet of new construction on campus. He – along with a dedicated team of administrators – increased both the capacity and caliber of the Stanford faculty and student body. These, along with other changes, turned the university into a leading destination for teaching, research, and scholarship.

“Sterling brought to the campus community of his day a special sense of planned, pragmatic forward movement,” said Nilan. “Yes, he took good advantage of the opportunities of the era, but he did so while balancing widely differing viewpoints and expectations – among alumni and trustees, faculty, staff, and students, not to mention Stanford’s neighbors and the public – of what the result should look like. And he did so as those opportunities waxed and waned more than once.”

Nilan worked with contributing editor and former Stanford News Service writer and editor Karen E. Bartholomew, ’71, to complete what Cassius “Cash” Kirk, ’51, who was staff counsel for business affairs, began in his retirement before passing away in 2014.

Over the subsequent decade, the project evolved to be a comprehensive look at Sterling’s tenure, chronicled in a glossy, 696-page book with hundreds of archival, black and white photographs.

Much of the information would have been officially documented in a comprehensive report Sterling was set to present to trustees at the end of his presidency, had it not been for an arson attack on his office two months before he retired. There are no annual reports of the president either, as Sterling had convinced the board that this final evaluation would be in lieu of the yearly reviews.

Now, Nilan, Kirk, and Bartholomew’s book fills that absence, drawing on extensive archival material that provides a glimpse into who Sterling was as a person as well as a leader.

“It is right now the best, most authoritative, and comprehensive book on those transformative years under Wallace Sterling,” said Stanford Historical Society (SHS) President Larry Horton ’62, MA ’66. SHS and various donors have underwritten this scholarly endeavor chronicling Sterling’s contributions to the Stanford campus.

Overseeing exponential growth

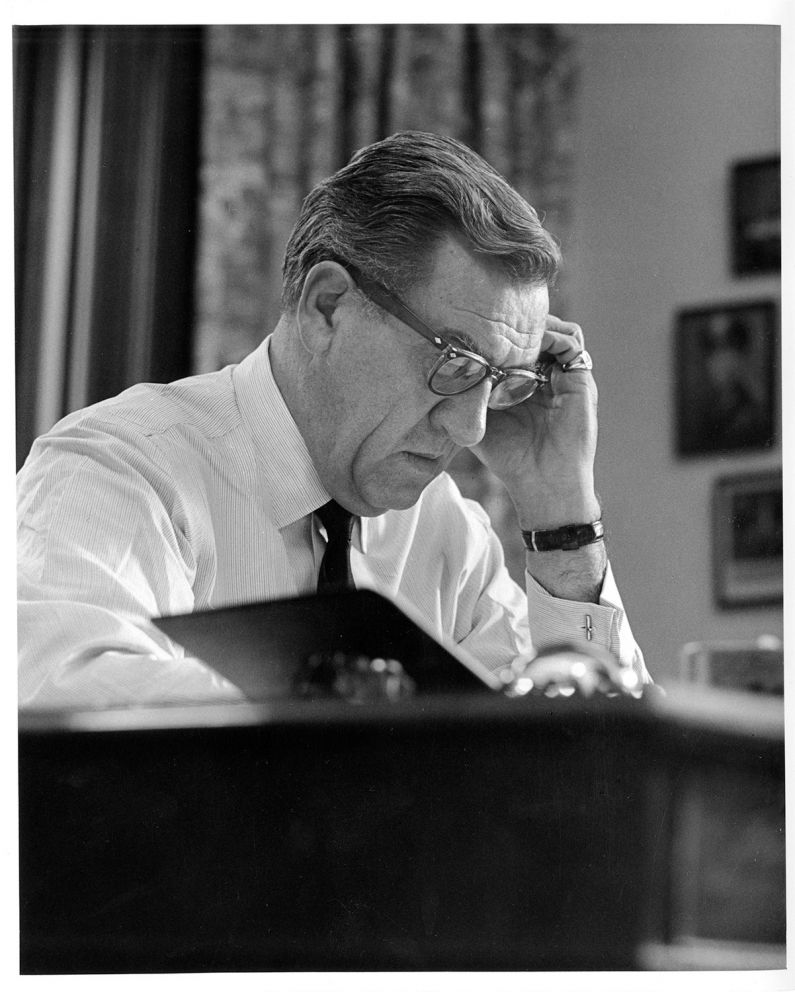

President J.E. Wallace Sterling at his desk in 1960. (Image credit: Jack Fields/Stanford University Archives)

Sterling also made substantial shifts to the university’s governance structure, working with a team of people to implement change – relationships which the authors also outline. Sterling wanted more faculty involvement in university affairs, for example, and encouraged their participation on advisory committees and through administrative roles.

Sterling established the Office of the Provost, promoting Frederick Terman to the position, in which he served from 1955-1965. Terman was tasked to do what he did as dean of the School of Engineering, but for the entire university, including the humanities and social sciences. His efforts also helped spur technological innovation at Stanford, which ultimately led to the rapid growth of Silicon Valley.

Sterling also radically transformed the university’s fundraising efforts, exponentially growing the university’s endowment from $41 million in 1949 to $268 million by 1968.

Sterling also oversaw the development of Stanford lands, including building the Stanford Research Park, the Stanford Shopping Center, and experiments with unaffiliated residential housing.

“Throughout his presidency, he employed his principle of gradualism, or as he put it, “the art of doing easily tomorrow what could be done today over a dead body,” Nilan said.

Managing during turbulent times

The authors also capture the social and political complexities that drummed throughout Sterling’s presidency.

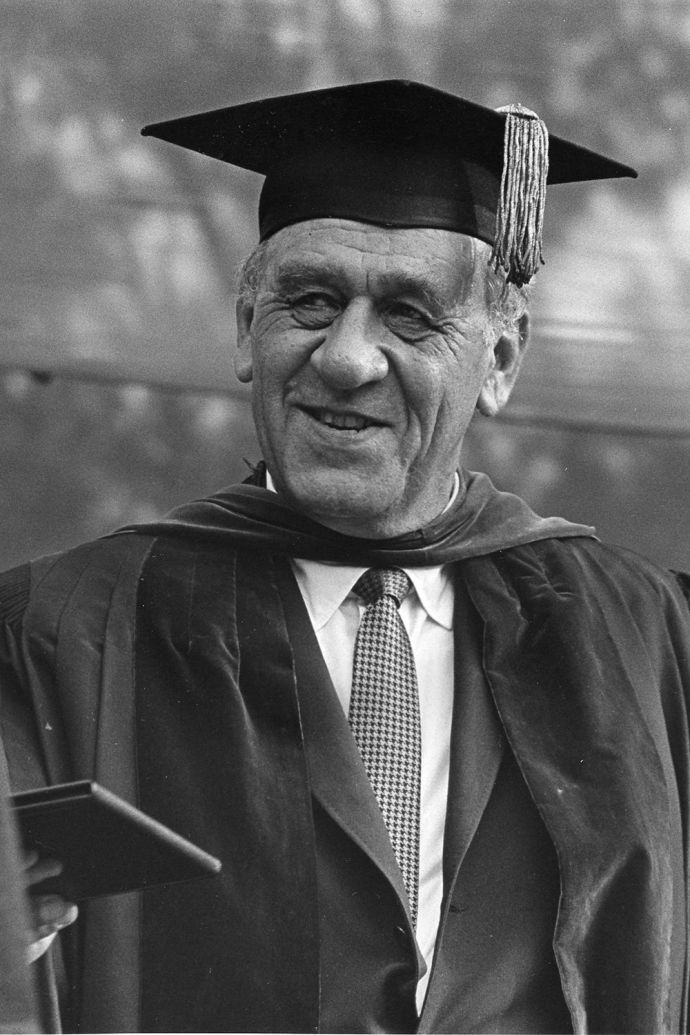

President Wallace Sterling hands out diplomas at his final commencement in 1968. (Image credit: Stanford News Service)

In the 1950s, there was the conflict in Korea, as well as escalating Cold War tensions and McCarthyism – U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s aggressive campaign to investigate communist party infiltration in American institutions and academia. Here, Sterling had to navigate pressures from across the campus community, including following the signing of a petition by faculty supporting Adlai Stevenson, a politician who was critical of McCarthy and what he represented. A few years later, more tensions arose when a Russian-born faculty member was subpoenaed to appear before a subcommittee of the U.S. House on Unamerican Activities.

Repeatedly, Sterling supported students and faculty on grounds of academic freedom and free speech – while being subjected to what Nilan described as a “pounding” from influential anti-Communist critics, especially alumni.

The 1960s saw the Vietnam War and with it, an active, anti-war movement across the country and at Stanford. There was the growing civil rights movement as well, which also spurred student protests on campus.

The authors chronicle how some of these demonstrations catalyzed change for the university, including the influential “Take Back the Mic” campaign: Four days after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Black Student Union (BSU) members took over a discussion being held at Memorial Auditorium with Provost Richard Lyman and other white, male professors. BSU members called for an increase in support for Black students, among other demands.

Sterling and Lyman engaged with BSU members and ultimately, nine of their ten demands were met, helping shape both Black and minority programming in the years to follow.

During this period, students were eager for change in campus policy, particularly some of the outdated, gendered residential rules – one of which included permitting men to live off campus, while denying women the same privilege. Here too, Sterling worked with student leaders to pioneer new housing and social policies.

“In the later 1960s, as now, when Americans wavered in support of higher education and doubted the value of a college degree, Sterling remained convinced that universities were essential to a humane, enlightened, and ever-improving society,” said Nilan. “He firmly believed that the Stanford community should be ‘proud of its past, relevant to the present, and open to the future.’”

Leading ‘like a coach’

Sterling’s journey to Stanford began as a graduate student: He earned his Ph.D. in history in 1938.

He had also been an accomplished collegiate football player and coach and remained just as devoted as a fan, revitalizing athletics programs as well as academics during his presidency.

Sterling’s sportsmanship was also reflected in his leadership style.

“I was impressed that many viewed him as the ultimate successful coach: a superb recruiter who sought out and utilized individual talent but insisted on team play, who gave his team his full confidence but took final responsibility,” Nilan said. “He knew action on the field rarely goes as expected but painstaking, innovative planning provides the advantage. Like a good coach, he considered it his job to take all the blame and share all the credit.”