Family trees, photo albums, and grandparents are often the go-to sources of information for people curious to know who their relatives were. Genetic ancestry is also a useful tool, but these measurements typically provide data on percentages of different populations in a person’s ancestry, not on specific people. Now, a new study led by researchers from Stanford and the University of Southern California introduces a new way to think about genetic ancestry, revealing information that approximates the number of people from a source population.

The researchers apply this new approach to the genetic and genealogical history of African Americans from the 1600s to the present to estimate the number of African and European ancestors who appear in a randomly chosen African American person’s genealogy. The authors provide context for their results by using a historical book written about several generations of the family of Michelle Obama, the former first lady of the United States, as an example.

Jazlyn Mooney, a former postdoctoral scholar in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, now a Gabilan Assistant Professor of Quantitative and Computational Biology at USC, is the lead author. Noah Rosenberg, the Stanford Professor of Population Genetics and Society and professor of biology in the School of Humanities and Sciences, is the senior author. The study summarizing their results published July 6 in Genetics and is the cover story.

Here, Mooney and Rosenberg discuss their new approach and how it helps fill a gap in the ancestry of African American people descended from Africans forcibly transported to the United States as enslaved captives during the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

How did this study come about? What sparked your interest in this topic?

Rosenberg: Genetic ancestry is often reported in terms of estimated fractions of genomes that trace to specific source populations. But there are many ways for a person to have the same ancestry level – for example, one grandparent from a population, two great-grandparents, or four great-great-grandparents would all lead to 25% ancestry. So it can be hard to interpret ancestry fractions in relation to family trees. This study tries to think about ancestry fractions genealogically: How many specific ancestors in a person’s genealogy contribute to the ancestry fraction, and when did they live?

Mooney: I was really excited when Noah and I talked about this project because we had the ability to fill in a gap about African American genealogies. Most African Americans, myself included, know very little about our family history prior to the late 1800s. This project and the model we developed gave us the opportunity to discover information about patterns in African American genealogies all the way back to the early 1600s.

What makes this study unique and how does it differ from previous research on this topic?

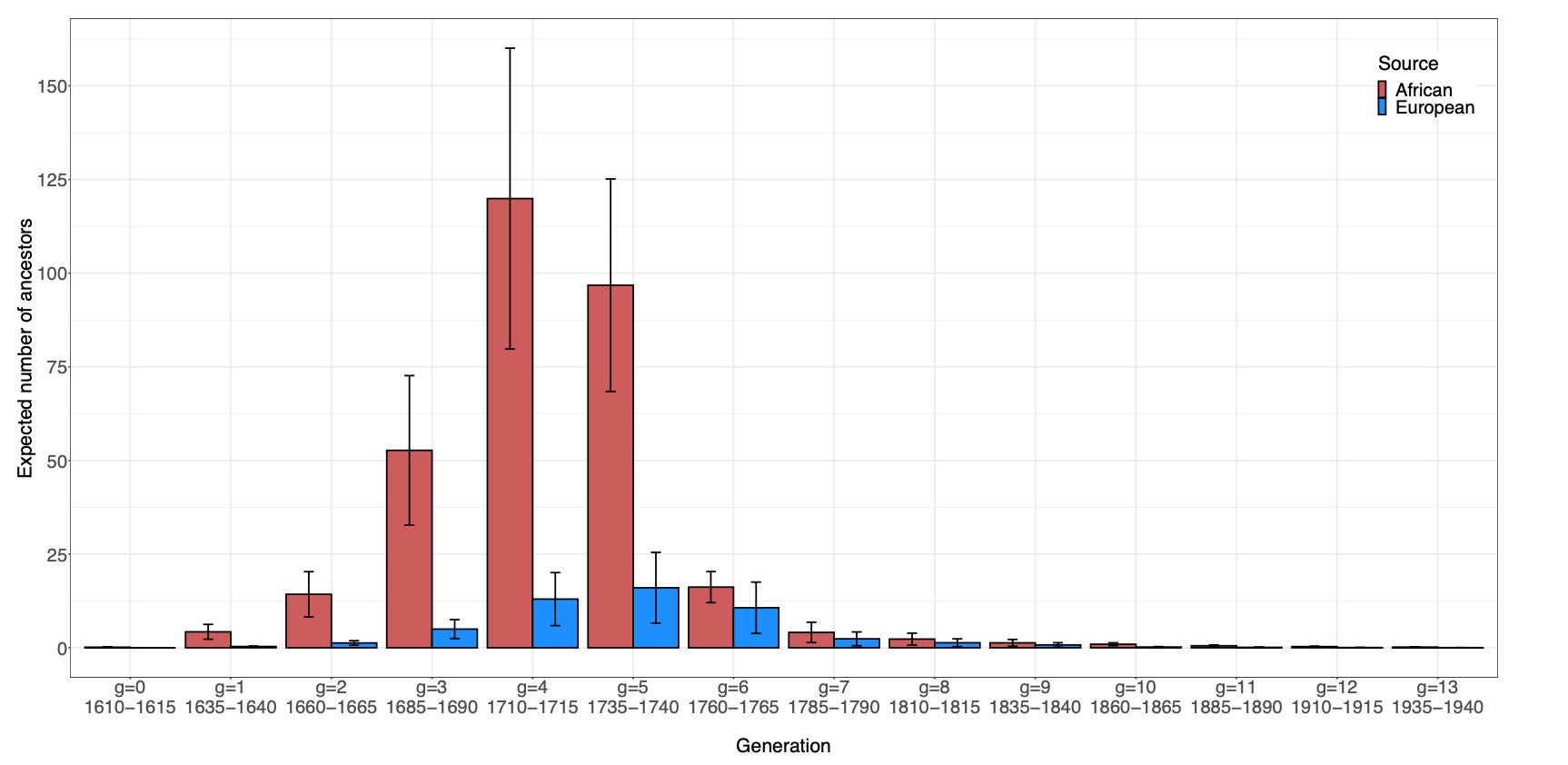

Mooney: The study is unique because the model produces estimates of the average number of genealogical ancestors, for a random African American individual born between 1960–1965, from each source population, African and European. These estimates are calculated for 13 different generations dating back to the 1600s. Previous genetic studies of African American population history have not thought about estimating this quantity.

What did you find, and were any of the results unexpected?

Mooney: We found that, for a randomly selected African American individual born between 1960–1965, one would expect them to have on average 314 African and 51 European genealogical ancestors. In other words, if you trace the genealogical lines of a typical African American from this cohort all the way back until the lines reach African ancestors and European or European American ancestors, we estimate that 314 lines reach Africans and 51 reach Europeans or European Americans.

Rosenberg: The model computes the times when the various African and European genealogical lineages are reached. At first, we were surprised that the largest number of African genealogical ancestors was in the early 1700s rather than during the peak of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the late 1700s. It does make sense though. A genealogical line traced back to the late 1700s might reach an African who had recently been transported. But it might also reach an African American descended from Africans transported in the early 1700s. Because of the passage of the few extra generations between the early and late 1700s, that line alone can add many African ancestors to the total, from the early 1700s or even earlier. Even though many lines reach Africans in the late 1700s, the ones that trace earlier end up adding a larger number of African ancestors.

Estimated mean number of African and European ancestors in different generations (denoted “g”), for African Americans born between 1960–1965. Error bars show standard deviations. (Image credit: Mooney et al. 2023)

How is the geneological study of Michelle Obama’s family tree used to help illustrate the meaning of this study’s results?

Mooney: Michelle Obama was born in 1964. She is a great example for thinking about our model since her family history has many features typical of African American genealogies in the most recent generations. Further, despite an extensive investigation, the book about her family tree was only able to recover additional information about one European ancestor and none of the African ancestors. I think Michelle Obama’s family history really contextualizes the study’s primary goal of recovering information about missing African and European ancestors quite well.

Rosenberg: What’s also interesting is the timing of the identified European American. The model estimates that about half of African Americans born between 1960–1965 have at least one European or European American ancestor born around the 1835–1840 window. For Michelle Obama, the named European American, a member of the family to which one of her African American ancestors was enslaved, was born in 1839.

How might these findings be applied to help inform or fill in data gaps in an African American person’s ancestry?

Mooney: For African Americans who are learning about their ancestry, this research fills a gap in the information about their unknown African ancestors. Oftentimes, there are no historical or census records about their African ancestors, only European ancestors or very few African American ancestors. Our study provides some information about approximately how many African ancestors a typical person may have and when those ancestors lived.

What questions related to this study would you like to address next?

Rosenberg: With the randomness of genetic transmission from parent to offspring, the genetic contributions of some of the genealogical ancestors to later descendants are lost. Backward in time, the fraction of a person’s genealogical ancestors who are also genetic ancestors dissipates quite a bit for ancestors 200 to 400 years before the person was born. In our next study, we’re trying to understand how many of the genealogical ancestors are likely to be genetic ancestors as well.

Additional Stanford co-authors are Lily Agranat-Tamir and Jonathan K. Pritchard. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, the Council for Higher Education of Israel Scholarship, and the Stanford Center for Computational, Evolutionary, and Human Genomics.

Media Contacts

Holly Alyssa MacCormick, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: hollymac@stanford.edu