Scientists have found more than 4,000 planets outside our solar system. Here, Stanford University exoplanet expert Bruce Macintosh and leader of the team behind the Gemini Planet Imager explains how scientists find alien worlds, why we should be skeptical about reports of “Earth-sized” and “habitable” exoplanets, and what exoplanet discoveries can tell us about the universe and our own planet.

“One of the most interesting things we’ve learned since finding the first exoplanet 30 years ago is how different the universe is compared to what we thought it was – how different other solar systems are from our own,” said Macintosh, a professor of physics in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “This makes me think that Earth is probably a very special planet.”

Here are the 14 questions Macintosh answered [click on the question to jump to his answer]:

- Four thousand exoplanets have been found in just 30 years. How is that possible?

- How did the Nobel Prize-winning discovery tip the scales?

- How do most astronomers “see” exoplanets?

- What else can we learn about exoplanets?

- The Gemini Planet Imager project that you’re a part of uses a different technique from the others you mentioned. How does it work?

- Is Earth special?

- We hear about exoplanets that are Earth-like. What does that mean?

- What about “habitable” exoplanets or the “habitable zone”?

- How do we look for life on exoplanets?

- Why should we care about exoplanets that aren’t like Earth?

- What big advances or discoveries do you think could be just around the corner?

- What exoplanet news would you be surprised to see?

- What upcoming developments for your group are you excited about?

- What’s next for astronomy as a field?

1. Four thousand exoplanets have been found in just 30 years. How is that possible?

The short answer: The 25-year-old paper that won the Nobel Prize in 2019 convinced scientists that they already had the tools to see exoplanets – then the discoveries kept rolling in.

Macintosh: Many people thought that other solar systems were like our own – a few small rocky planets closer to the sun, and some giant planets further out – and that it would, therefore, be nearly impossible to find exoplanets because our tools aren’t sensitive enough to see into those kinds of systems. This was such a popular idea that people working in the field early on had trouble getting access to telescopes and funding.

There were tentative early discoveries but they didn’t match expectations, so they didn’t really change the field that much. Then, the 1995 paper, from Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz – that led to their winning the Nobel Prize in 2019 – strongly argued that we really were seeing exoplanets. Another half-dozen exoplanet discoveries came right after because they had just been sitting in peoples’ closets, unanalyzed, waiting for this kind of strong argument.

It turns out, also, the universe seems to favor small planets and, so, as the techniques got more sensitive, they’ve found more and more.

[Back to the list of questions]

2. How did the Nobel Prize-winning discovery tip the scales?

The short answer: The scientists were confident and very thorough in eliminating other possible (non-exoplanet) explanations for their findings.

Macintosh: It was a combination of really carefully ruling out other explanations and of having the confidence to assert that they found an exoplanet. Their measurements required colleagues to accept a planet – now called 51 Pegasi b – unlike anything they had imagined: hot, Jupiter-sized, closer to its sun than Earth is to ours, and with an orbit of less than five days.

Along the way, Mayor and Queloz had to rule out other possibilities, such as the suggestion that their measurements were actually showing a star that was expanding and contracting, or that they had found something larger orbiting a star and were merely observing it from an odd angle that made the orbiting object seem planet-sized. It also helped that many others made similar measurements, so unexpected exoplanets started to become more likely than some weird chance alignment.

[Back to the list of questions]

3. How do most astronomers “see” exoplanets?

The short answer: We usually use indirect methods that allow us to see the effects of the planet but not the planets themselves.

Macintosh: There are two main methods that we discover planets by right now: the Doppler method and the transit method. Both of these are indirect ways of “seeing” planets, which means we are observing their effects but not the planets themselves. Seeing planets directly is very hard because they are so close to their stars and so much fainter by comparison.

The Doppler method measures how the planet’s gravity tugs on the star that it’s orbiting day after day, year after year. We can’t see the thing that’s pulling on the star but we can calculate its mass. This was the technique that was used by the two researchers awarded the Nobel Prize in 2019.

The transit method involves measuring changes in light from the star. If a planet passes in front of a star, it will block some of the light from the star, causing it to dim. (If you were looking at our solar system from far away in just the right direction, you’d see our sun get about 1 percent fainter every 12 years when Jupiter gets in the way.) For this to work, though, you have to get very lucky – the planet and star have to line up just so. If you’re not feeling mega-lucky, then you have to look at tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of stars to find the few that are lined up just right. With modern big digital cameras and modern computing, that’s possible. Automated software finds the possible planets, then astronomers figure out which ones are real and interesting. Because it’s so automated and computerized, that’s the way most planets have been discovered so far.

Both of these methods work best when planets are close to their star. In a universe full of solar systems just like our own they would almost never work. The first amazing surprise about exoplanets is that there are so many planets of all kinds and sizes so close to their stars.

[Back to the list of questions]

4. What else can we learn about exoplanets?

The short answer: We can calculate their mass or radius, maybe their density and a little bit of vague information about their atmosphere. We can also sometimes estimate their age.

Macintosh: When you use these techniques in the simplest way, they tell you either the mass or the radius of the planet. If you’re lucky and can learn both, you can calculate the density (how much each cubic meter of the planet weighs), which can be a clue as to what it’s made of – but you can’t really tell the difference between a planet that’s half rock and half big, puffy atmosphere versus a planet that’s all water.

With modern telescopes and instruments, if the light from the star passed through a transiting planet’s atmosphere before it gets to you, you can learn something about its atmospheric composition. Right now, for that to work, it has to be a big planet – at least Neptune-sized – and you have to see it transit many times. By analyzing that light, we can find evidence of individual molecules in the planet’s atmosphere – like carbon monoxide or water vapor or methane – and learn things about the temperature of the planet or the pressure in its atmosphere.

As for age, you can usually tell if a star is really young, and that means its planets (if it has any) will also be young.

[Back to the list of questions]

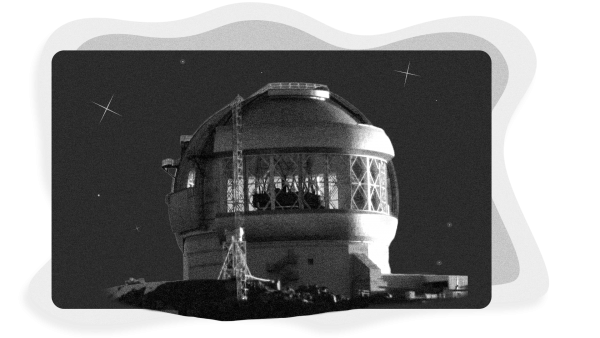

5. The Gemini Planet Imager project that you’re a part of uses a different technique from the others you mentioned. How does it work?

The short answer: While other techniques find exoplanets by recording their effects, the Gemini Planet Imager takes images of the exoplanets themselves.

Macintosh: The Gemini Planet Imager, which began scientific operations in 2014, directly sees exoplanets. Now, that doesn’t mean we see continents and oceans. We see two dots, the star and the planet. But it’s really hard to get even that! Jupiter is a billion – a thousand million – times fainter than the sun and they’re very close together by planetary standards, so it’s like trying to look for a firefly next to a lighthouse.

We incorporate a lot of technology to block out the “lighthouse” and see the tiny “firefly.” This works best for exoplanets that are far from their stars – like where Saturn, Neptune or Uranus are in our solar system. And we can only see planets that are extra bright, which means planets that are young. (When a giant Jupiter-like planet forms, a lot of energy gets released; so if you catch a baby planet, it’ll still be hot and glowing.) It turns out there aren’t very many exoplanets that fit that criteria, so we don’t get 4,000 of them, but we cover exoplanets that other techniques aren’t studying.

Right now, direct imaging – with the Gemini Planet Imager and other instruments like it – is probably providing some of the best measurements that we have of planetary atmosphere composition because you have direct light that you can analyze. We can see what chemical substances are present in the planet’s atmosphere, learn about clouds and chemistry. The limitation, for now, is the planet has to be bright, far from its star, young and big – about twice the size of Jupiter.

[Back to the list of questions]

6. Is Earth special?

The short answer: So far, we haven’t seen anything else like it.

Macintosh: The challenge right now is that we can’t see exoplanets that are just like Earth with our current technologies. There are many that are Earth-sized but we can only see them around stars that are really different from our sun. And we can only really measure size, so we don’t know how they formed or definitive details about what they’re made of.

So, the question we’re trying to answer now is whether our solar system is rare – because a solar system like ours would be more likely to have an Earth. From what we’ve seen so far, planets overall huddle closer to their stars than the planets in our solar system. If every star had a solar system like our own, we’d probably know about maybe 10 planets in the entire surveyed universe but, instead, we’ve found about 4,000.

Does that mean the combination of events that led to a well-behaved solar system with a planet that people can evolve on is very rare? Or are these solar systems just hard to find?

[Back to the list of questions]

7. We hear about exoplanets that are Earth-like. What does that mean?

The short answer: It just means they’re Earth-sized.

Macintosh: Right now, every time you see the word “Earth-like” you should replace it with the word “Earth-sized,” because that’s what we’re measuring. Here’s why that matters: Venus is an Earth-sized planet but isn’t Earth-like in other ways we care about.

Given that we can’t measure the composition for an Earth-sized planet or for planets that are orbiting stars like our own sun, there’s certainly no evidence for a truly Earth-like planet.

I mentioned that the transit method can get some measurements of exoplanets – specifically hot versions of Neptune. In those, we do see the same elements that are present that are present in our solar system, like water and carbon dioxide. So that might imply that smaller planets are Earth-like, but I think that’s optimistic.

[Back to the list of questions]

8. What about “habitable” exoplanets or the “habitable zone”?

The short answer: We don’t have any way of knowing whether we could live on any of the exoplanets we’ve discovered.

Macintosh: You should think of “habitable zone” as the “gets the right amount of sunlight zone,” where you get enough energy from the sun that you could have liquid water on your surface.

Now, you really need to understand a planet’s history to say whether humans could survive there. Another Venus example: Some definitions put Venus in the habitable zone, but it has a surface temperature of nearly 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit and rains sulfuric acid and the pressure would crush you.

Unfortunately, we don’t have the ability to measure much beyond sunlight and size right now, which suggests we shouldn’t really even use the word “habitable” for a long time.

[Back to the list of questions]

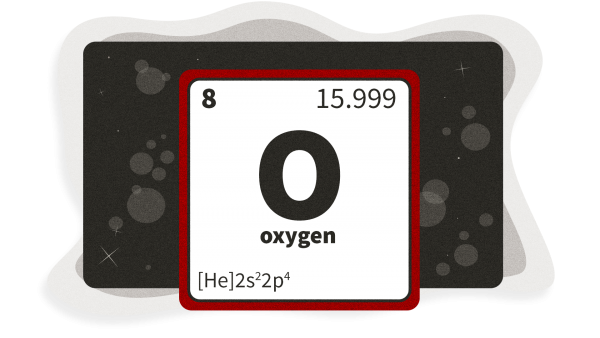

9. How do we look for life on exoplanets?

The short answer: We look for stuff that is associated with life on Earth, like oxygen or liquid water.

Macintosh: With telescopes, looking at something 100 light-years away, we can’t see continents or oceans. So we look for other hints of life that are familiar to us, like oxygen or carbon-based life that involves liquid water. Evidence of life is even stronger if we find additional chemicals that, as far as we know, only exist together as a result of life – like having water and methane and oxygen. We can’t even quite see those chemicals now, but future instruments – the James Webb Space Telescope, extremely large telescopes on the ground, and maybe future very large space telescopes – will be able to look for oxygen and water.

There could be a bunch of other pathways for life that we haven’t understood yet. In our solar system, people think you can have life under the ice of some of the moons of the outer planets. We’ve flown spacecraft by these planets but we still can’t tell. There are also people who think there could be life on Mars – but we don’t really know for sure, even though we have robots driving on the surface. So figuring out whether there’s life 100 light-years away is going to be pretty uncertain!

We’re embarrassingly human-centric in what we choose to look for as a sign of life. But if we find an exoplanet with chemistry that looks unimaginably weird, then people will try to understand if there’s a biological explanation for that.

[Back to the list of questions]

10. Why should we care about exoplanets that aren’t like Earth?

The short answer: The more we know about other exoplanets, the more we can figure out about what makes Earth special – or not.

Macintosh: Exoplanets can help tell us about the processes that make planets form and evolve, and understanding this could be key to finding exoplanets that really are like Earth.

We already know there are probably a fair number of planets the right distance from the sun (in the habitable zone) and the right size (Earth-like), but one thing that’s still special about Earth is it has the right amount of atmosphere. That’s related to how it formed and the history of our solar system. So, if we know that other solar systems formed with a similar history, then we could infer the planets that formed in those solar systems might have an Earth-like atmosphere.

We’re also using whatever we can observe now to make our telescopes better. My group studies planets twice the size of Jupiter, and we can measure what they’re made out of. Once we have better telescopes in space, the software we’ll use is the same software we’re going to use if we ever measure the composition of a planet like Earth.

[Back to the list of questions]

11. What big advances or discoveries do you think could be just around the corner?

The short answer: There could be an announcement of oxygen on an Earth-sized planet – but I doubt it.

Macintosh: If we get lucky, we’ll be able to measure the composition of Earth-sized exoplanets in the habitable zone using transits. We recently had the first really good spectrum of a habitable zone planet but it was twice the size of Earth, which makes it not especially habitable.

There’s a mission up right now called the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) that is supposed to discover planets in the habitable zone of small stars that are near Earth. If we launch the James Webb Space Telescope, it would be sensitive enough to measure their light or spectra. With both of these instruments, over the next six years or so, we’ll move from barely understanding the atmospheric composition of one or two small planets to knowing dozens – a few of which will be right in this habitable zone, Earth-sized range. Oxygen turns out to be really hard for James Webb to detect but, if we get lucky, an exoplanet might have a big, puffy atmosphere that’s easy to see.

We’ll also get the first real measurements of the atmospheric composition from these systems that are weird and nothing like our own. What are these planets really made of?

As a pessimistic person in the field, I don’t think we’ll see oxygen from an Earth-like planet, but I think we will learn a huge amount about the atmospheric composition of hundreds and hundreds of planets. For now, the hardware to do it is sitting in a clean room in Los Angeles and fingers crossed it’ll make it out of there and into space.

[Back to the list of questions]

12. What exoplanet news would you be surprised to see?

The short answer: Anything that says we’ve found life because we found oxygen.

Macintosh: I’d tell people to be wary of anything that says we found oxygen and that means there is life.

If we get a detection of oxygen with James Webb, it will not be a strong, significant measurement. So there’s some chance that it just isn’t oxygen. Even if it is, I don’t think we’ll have enough context to know for sure that a biological explanation is the most probable explanation – let alone a definite explanation.

[Back to the list of questions]

13. What upcoming developments for your group are you excited about?

The short answer: The Gemini Planet Imager is going to look at new kinds of exoplanets. We’re also hoping to send a telescope to space and we’re developing a “star shade” for a new kind of planet hunting.

Macintosh: Right now, we’re studying a bunch of planets with our Gemini Planet Imager in Chile. The smallest one we found is about 25 million years old, two to three times the mass of Jupiter, and it kind of orbits where Saturn is. We’re going to rebuild the instrument, make it more sensitive and move it to a telescope in Hawaii. This lets us look at a different part of the sky and that location has better atmospheric conditions.

From our first survey, we didn’t see any of these giant planets in the outer parts of solar systems that had stars like the sun. We saw a few around stars that were more massive than the sun. Now, we want to push the sensitivity to look for planets that are even closer in size to Jupiter – which might actually be very rare. We’ll be also able to look at “extra-young baby Jupiters” that are actively building up toward their full size, which could tell us more about planetary formation.

To get exoplanets smaller than Jupiter, we’re going to need a space mission. By going into space, our measurements would be a hundred or a thousand times more sensitive than what we’re doing right now, which is pretty impressive. We’re working on a the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, which is supposed to launch around 2025, and it will carry some of the technology we use into space. For now, we’re just trying to demonstrate the technology, so it will still be limited to older “big Jupiters.” But, if it works like we hope it does, this same technology would be able to see Earth-like planets if it’s put on a bigger, slightly better telescope.

There’s a different approach to detecting planets that I’ve been working on with Simone D’Amico from our Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. It’s called a star shade and uses two spacecraft: one to block out the light from the star and one to observe the exoplanet. We have a concept for a mini version of the star shade that would test the technology before somebody built a full-size, billion-dollar version. Whether we’ll get to do that isn’t clear but it’s a cool concept.

[Back to the list of questions]

14. What’s next for astronomy as a field?

The short answer: We’re trying to decide!

Macintosh: Astronomy is trying to decide what we’re going to do over the next 20 years, what our next big space mission will be. Do we try to look at Earth-like planets? Or do we study gravitational waves more? Or do we study X-rays from black holes more?

I’m involved in the process for figuring this out, called the Decadal Survey. It was a lot of time in small meeting rooms with limited oxygen – and now it’s a lot of video conference meetings – but it’s an important discussion about the future of astrophysics with a lot of smart people. Twenty years from now, I may not be practicing astrophysics anymore, but the decisions we’re making now could determine what missions my postdocs and students will be on then.

[Back to the list of questions]

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.