Daniel Freedman, a visiting professor at the Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics (SITP), is a co-recipient of a Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for his role in the invention of supergravity, a deeply influential theoretical blueprint for unifying all of nature’s fundamental interactions.

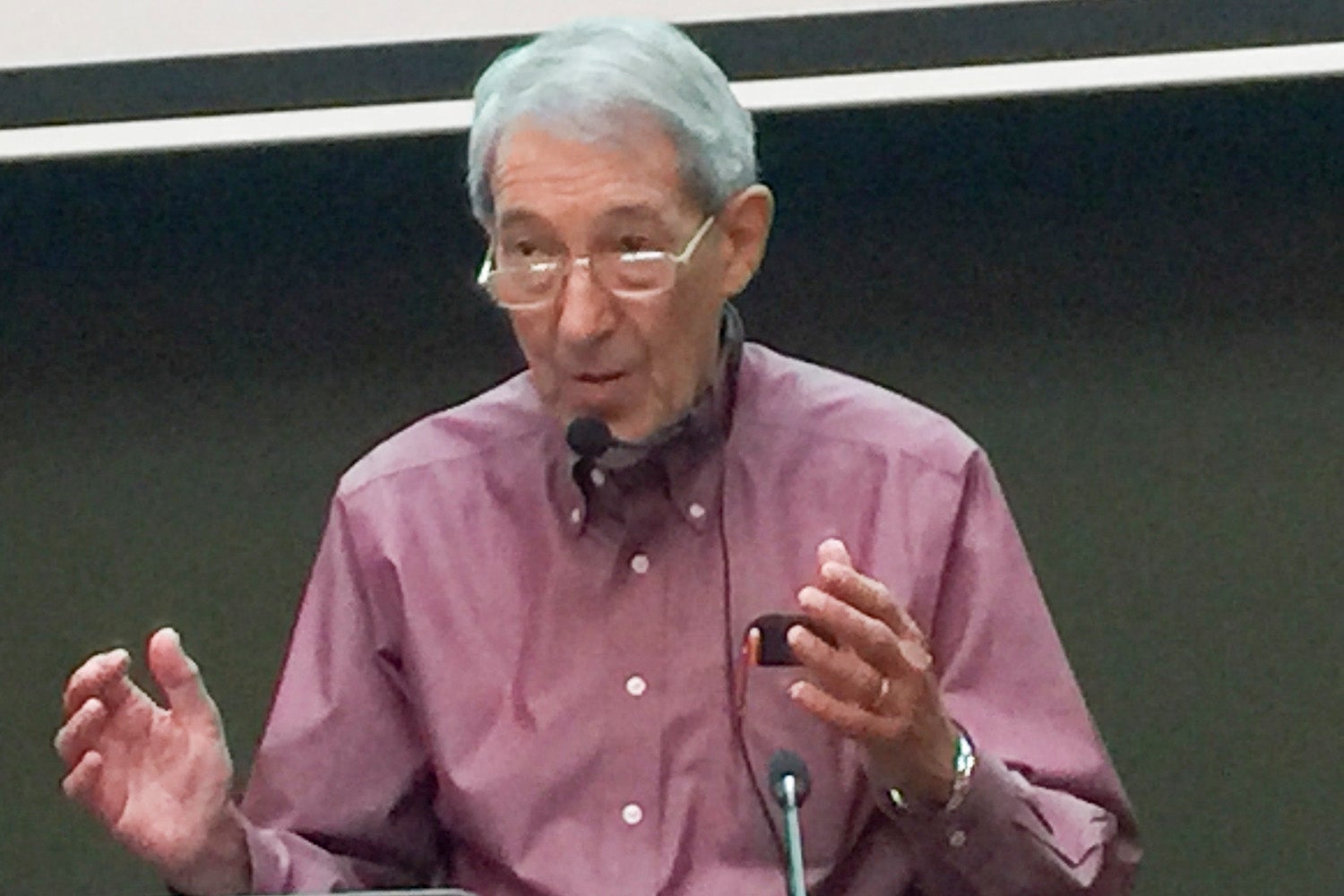

Daniel Freedman, shown lecturing at a conference in Leuven, Belgium, in September 2018, will share the $3 million prize with two other physicists. (Image credit: Courtesy Miriam Freedman)

Freedman, who is an emeritus professor of applied mathematics and theoretical physics at MIT, shares the $3 million prize with Sergio Ferrara and Peter van Nieuwenhuizen, who are at CERN and SUNY Stony Brook, respectively.

In 1976, the trio drew upon a recently developed principle in physics known as supersymmetry to propose a modified version of general relativity. This new version successfully integrates gravity with nature’s three other fundamental forces.

Despite recently turning 80, Freedman’s enthusiasm for physics shows no signs of abatement. Freedman received word of his Breakthrough Prize while at the Aspen Center for Physics, where he was attending workshops on new developments in quantum field theory and preparing for a new collaboration with colleagues from Princeton.

Freedman was informed of the news through a phone call from Stanford physicist Andrei Linde, who is a member of the Breakthrough Prize selection committee.

“I was overwhelmed,” Freedman recalled. “I just said, ‘Wow, wow, wow.’”

In a follow-up email to colleagues, Freedman wrote, “I still haven’t stepped down off cloud nine. Somehow I must get back to my calculations.”

Toward unity

Supergravity was part of a string of revolutionary physics discoveries in the 1970s that were sparked by the realization that two of nature’s fundamental forces – electromagnetism, responsible for electricity and magnetism, and the weak nuclear force, which underlies some forms of radioactivity – were actually different facets of a single, primordial force that splintered when the universe was starless and young.

“I still haven’t stepped down off cloud nine.”

—Daniel Freedman

Visiting Professor, Stanford Institute for Theoretical Physics

This discovery helped set the stage for the development of the Standard Model, a theoretical framework that describes not only the particles mediating this “electroweak” force but also the strong force, which binds protons and neutrons together inside atoms.

The Standard Model marked a monumental milestone in physicists’ understanding of nature, but it was incomplete. It failed, for instance, to explain dark matter, an invisible substance permeating the universe, or provide an answer for why gravity is so much weaker than even the weak force – a conundrum known as the hierarchy problem.

Then, in 1973, physicists proposed supersymmetry, a theory that addressed many of the Standard Model’s shortcomings by invoking the existence of a new class of hypothetical partner particles that mirrored all of the known particles in nature.

Supersymmetry suggests the possibility that dark matter is made up of one or more of these partner particles, or super-partners, and that the strength of the electroweak force stems from a careful balancing act between the equal but opposite energy contributions of partner particles.

In 1976, Freedman, Ferrara, and van Nieuwenhuizen expanded upon supersymmetry to incorporate gravity. Their theory of supergravity introduced a new particle called the gravitino as the super-partner to the graviton, the quantum carrier of gravity proposed by Albert Einstein.

“Supersymmetry unified particle physics with the special theory of relativity, which describes space-time, but not with general relativity, which describes gravity,” said Linde, the Harald Trap Friis Professor at Stanford. “This last step was crucial and extremely difficult.”

Supergravity has helped shape the theoretical physics landscape for over 40 years, according to Shamit Kachru, chair of the Department of Physics at Stanford. “Dan’s work on supergravity had a tremendous impact on many fields of physics, including particle physics, quantum gravity, string theory, and on questions in geometry, topology, and number theory,” said Kachru, who is also the Wells Family Director at SITP. “My own career has involved work on supergravity models coming out of string theory that are inspired by Dan’s work.”

Stanford theoretical physicist Renata Kallosh noted that supergravity also played an instrumental role in what’s known as the KKLT construction – a version of string theory developed at Stanford nearly 20 years ago with Kallosh’s help that remains one of the best explanations for dark energy, the mysterious universal repulsive force pushing space-time apart.

“We are all so happy for Dan, Peter, and Sergio,” Kallosh said. “We are so lucky to have Dan here. He is not only a great physicist but also a great person.”

Secretive nature

A visiting scholar at SITP for more than five years, Freedman has collaborated on new projects, participated in seminars and speaker events, and taught graduate-level courses on supergravity. He is known for assigning students homework with recommended classical musical accompaniment for each problem.

“Dan has been a tremendously good citizen at SITP,” Kachru said. “As a long-term visitor, Dan brings special expertise and skills – at the highest level – that are different from the mix we have at SITP without him. This is a feature of visiting scholars more generally that makes them so valuable to us.”

Freedman said he is “hopeful but not optimistic” that evidence for gravitinos or other super-partners predicted by supersymmetry and supergravity will be found during his lifetime.

“There are purely theoretical arguments that say to me that supersymmetry is inevitable,” Freedman said, “and if supersymmetry exists then supergravity is inevitable.”

Experiments at the Large Hadron Collider have so far failed to uncover any signs of super-partner particles, although physicists note that evidence for supersymmetry could still turn up as part of current searches for dark matter and primordial gravitational waves known as B-modes.

“Nature is not being very cooperative,” Freedman said. “She is hiding her secrets and not telling us the direction where the next step beyond the Standard Model lies.”

But Freedman doesn’t appear too bothered by nature’s secretiveness – if anything, he’s excited about mysteries left to be solved.

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Freedman and his co-laureates will be recognized at the 2020 Breakthrough Prize ceremony at NASA’s Hangar 1 on Sunday, November 3, 2019, where the winners of the annual Fundamental Physics prize will also be honored, along with the winners of the Breakthrough Prizes in Life Sciences and Mathematics.