A collaboration among Stanford archaeologists and scholars in China is helping reveal the culture and lives of Chinese migrants who traveled across the Pacific Ocean to the United States and other places during the 19th century.

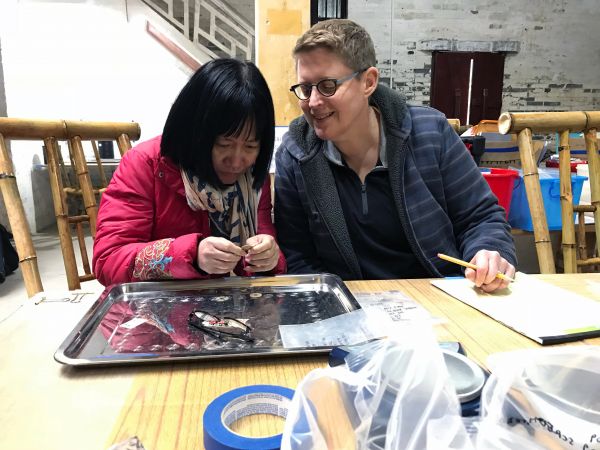

Stanford anthropologist Barbara Voss, right, and Jinhua (Selia) Tan, an associate professor of architecture at Wuyi University, examine coins recovered from subsurface testing at Cangdong village in southern China in December 2017. (Image credit: Courtesy Cangdong Village Project)

Displaced in their homeland by violence and economic hardship, the migrants helped shape many foundational aspects of the developing American West. They worked in mines, established Chinatowns and built railroads, including the First Transcontinental Railroad, until the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and anti-Chinese violence forced many of them to flee.

Researchers have excavated sites where Chinese migrants lived and worked in the United States, but their homes in China have not been studied until the recent efforts of an international research group, led by Stanford anthropologist Barbara Voss.

The group grew out of the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, which was created in 2012 by Stanford scholars to explore the largely unknown history of the Chinese migrants who built the First Transcontinental Railroad. The project is holding a public celebration of the 150th anniversary of the railroad completion on April 11.

That anniversary has special meaning to Stanford, which was created using much of the wealth Leland Stanford earned as one of the “Big Four” who oversaw construction of the western half of the First Transcontinental Railroad between California and Utah.

“It’s exciting to finally be able to look at the material culture and practices of migrants in their home villages,” said Voss, associate professor of anthropology at Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences, who has coordinated the project’s affiliated archaeology network. “Up to this point, archaeologists didn’t have that comparative data.”

Excavations in Cangdong

Go to the web site to view the video.

Over the past three years, Voss and a team of researchers excavated Cangdong, a village in the Pearl River Delta region of southern China’s Guangdong province. The village, where about 400 residents lived in the 1800s, is part of a five-county area that was home to most of the Chinese who migrated to the United States during the 19th century.

Voss and her team were invited to work at an architectural heritage program at Cangdong by Jinhua (Selia) Tan, an associate professor of architecture at Wuyi University. Researchers there found a variety of Chinese ceramic bowls. The patterns of some matched the types of bowls discovered at the sites of the camps of Chinese railroad workers in the United States.

Researchers also uncovered British-made ceramic plates, as well as American-made medicine bottles and clothing dating between the 1860s and 1912. This surprised Voss and her team because the findings suggest that Cangdong residents had access to a larger variety of imported goods than previously thought. Scholars have known that China traded with Britain and the United States during the 19th century, but the general perception of commerce during that time has been that China primarily imported raw materials and exported finished goods, Voss said.

A nuanced picture

“This research is helping us paint a much more nuanced picture of residents of the Pearl River Delta,” Voss said. “They were sophisticated consumers who had access to goods from around the world. This challenges the stereotype that Chinese migrants were isolated rice farmers who were not part of the world economic systems.”

Stanford anthropologist Barbara Voss discusses preliminary results of the archaeological work at Cangdong village, while Stanford anthropology doctoral candidate Laura Ng excavates in the foreground in December 2017. (Image credit: Courtesy Cangdong Village Project)

Voss said the excavation effort, called Cangdong Village Project, is a big step toward understanding the transnational relationship that existed between China and the United States during the 1800s.

“We cannot really understand North American history if we only look east to west,” Voss said. “We have to consider the formative role that the interconnection with Asia has always played in the development of the American West.”

Laura Ng, an anthropology doctoral candidate, accompanied Voss on archaeological surveys of the site in Cangdong. She said her favorite part was interacting with the people living in the village, almost all of whom have family overseas.

“It’s pretty amazing how people from these tiny, seemingly isolated villages have connections to places across the world,” Ng said.

This academic year, Ng has been studying another village, called Wo Hing, in the area that’s connected to migrants who moved to the Chinatowns that existed in Riverside and San Bernardino in Southern California from the 1870s until the 1920s.

Ng said the research is meaningful intellectually and personally for her. Ng’s parents, who immigrated from China to California in the 1980s, grew up in the same county, called Taishan, where she is now conducting her research. Her older ancestors also came to the United States generations ago, but never settled.

“It’s inspiring to do research that could help explain what it was like for Chinese migrants to be a part of two worlds back then,” Ng said. “By examining artifacts in China and the United States, we can get a better idea of how communities on both sides of the Pacific influenced each other.”

Media Contacts

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: (650) 497-4419, ashashkevich@stanford.edu