Winslow Briggs, a professor emeritus of biological sciences who explained how seedlings grow toward light, died Feb. 11 at Stanford University Medical Center. He was 90.

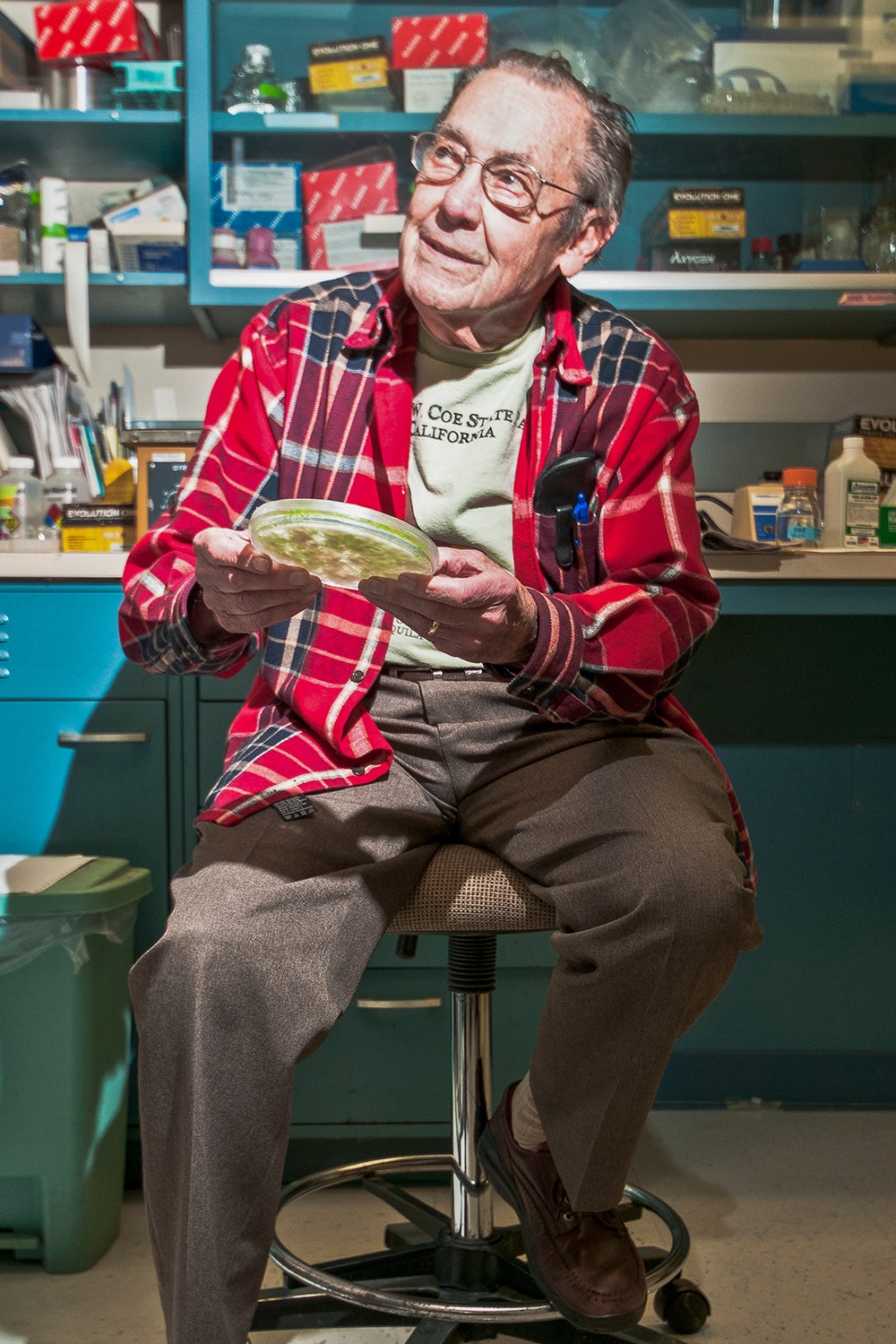

Winslow Briggs (Image credit: Robin Kempster)

Briggs established himself as a global leader in plant genetics and physiology, publishing landmark research on the molecular mechanisms that plants and other organisms use to sense and respond to light. He was remembered as a valuable colleague and friend.

“Winslow Briggs was a most generous and welcoming colleague for me when I joined the Stanford faculty in 1961,” said Philip Hanawalt, the Dr. Morris Herzstein Professor in Biology, Emeritus. “I appreciated his broad expertise in plant biology and he served importantly as an advisor to several of my graduate students.”

When a plant seedling germinates, it must be able to rapidly position itself to capture light as soon as it emerges from the soil. Briggs and his lab discovered and first characterized a pair of photo-sensitive receptors that mediate this response and enable the plant to grow toward the light so that it can convert solar energy, carbon dioxide and water into sugar – a process called photosynthesis.

Over the years, work by Briggs and others revealed that these two receptors contribute to a plant’s efficiency in other ways, including leaf growth and orientation, as well as the opening of the pores on a leaf’s surface through which it takes in the carbon dioxide needed to manufacture sugars.

“Winslow was a pioneer in understanding the role of light in plant development,” said Paul Ehrlich, the Bing Professor of Population Studies, Emeritus.

Briggs arrived at Stanford University in 1955 as an instructor in biological sciences after receiving his PhD from Harvard University. He had risen to full professor by 1967, when he left Stanford to take a faculty position at Harvard. He returned to Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences in 1973, when he also became the director of the Department of Plant Biology at the Carnegie Institution, a position he held for two decades.

After retirement in 1993, Briggs remained extremely influential in science as he pursued research on photoreceptors in plants and bacteria until the day of his death. Most recently, his team was working on elucidating the role of photoreceptors in the process by which symbiotic root bacteria can provide nitrogen to certain plants.

“Plants are stationary, which means that they have to evolve complex methods to take advantage of every available resource, including sunlight,” explained Zhiyong Wang, acting director of Carnegie’s Department of Plant Biology. “Receptors such as those discovered by Winslow, found broadly in both plants and microbes, are a crucial part of not only how plants respond to and take advantage of their environmental conditions, but also how bacteria interact with their animal and plant hosts.”

Joe Berry, acting director of Carnegie’s Department of Global Ecology, noted that Briggs was also recognized in his youth as an intrepid mountaineer with first ascents of peaks in Canada and Alaska.

Briggs also volunteered for 40 years at Henry W. Coe State Park, about which he published a book of trails and where, in 2007, he organized volunteers to study recovery after a massive wildfire. During that time he discovered that chemicals in smoke stimulate the sprouting of seeds of rare plants that may lie dormant for many years until awoken by fire.

Briggs was a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, the Botanical Society of America, the American Society of Plant Physiologists, the American Society of Photobiology, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the California Academy of Sciences.

In 2007, the American Society of Plant Biologists, of which he was president in 1975 and 1976, gave him the Adolph E. Gude, Jr. Award for his “service to the plant science community.” Two years later, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science awarded him the prestigious International Prize for Biology for his “outstanding contributions to the advancement of basic research.”

He is survived by his wife of 63 years, Ann, whom he met while they were students at Harvard, and by his daughters Marion, Lucia and Caroline, as well as four grandchildren and one great-grandchild.