Forgetting about a long-scheduled meeting or organizing two activities at the same time evokes a response that is familiar to everyone. People call those actions mistakes, blame themselves and apologize to those affected by their inconsistent behavior.

The feeling of self-blame and failure that most people get after messing up their plans is at the heart of the latest research from Stanford philosopher Michael Bratman.

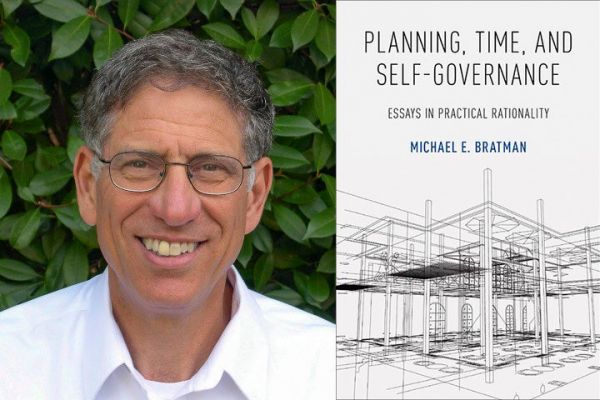

Stanford philosopher Michael Bratman explores how and why people plan their lives in his new book. (Image credit: Courtesy Michael Bratman)

Why do people get upset when something about their planning goes awry? Bratman argues that the negative emotions in those situations represent humans’ inherent need to abide by so-called rational norms of consistency, coherence and stability that help guide their planning.

“Fitting together different plans in a coherent, consistent and stable way is part of what it means for humans to have unified thinking concerning what they are doing,” Bratman said, noting that the existence of those norms helps make planning rational and is essential to people’s sense of freedom and autonomy over their own lives.

Bratman, the U.G. and Abbie Birch Durfee Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, details a way to understand why rational planning matters to people in his recently published book, Planning, Time, and Self-Governance.

The power of planning

Bratman’s new research is a continuation of his extensive work on the role of planning in human activity.

In his early work, Bratman developed a theory describing how people order their lives. He argued that people’s intentions are critical to the realization of their plans: having a cavity requires scheduling a dentist appointment; an expired driver’s license means a trip to the Department of Motor Vehicles.

In groups, intentions shared by two or more people also help organize complicated social activities over time, such as planting and sustaining a community garden, Bratman said.

“We have organized ourselves into societies that have built buildings, paved roads and raised food,” Bratman said. “It’s hard to see how those things would come about if we were not able to plan.”

Explaining rational planning

“My original idea for why planning gives us all these benefits was because it is being guided by certain rationality norms,” Bratman said.

Bratman identified three norms that encourage rational planning: consistency, coherence and stability.

In a hypothetical example, imagine Anna wakes up with a toothache and realizes that she should probably visit a dentist. The norm of consistency – not doing two things at once – forces her to avoid double-booking a dentist appointment and a trip to the DMV at the same time. The norm of coherence – organizing the means to achieve plans – pushes her to order a taxi that will get her to the dentist’s office. The norm of stability – sticking to one’s original plans – encourages her not to skip the dentist because she already ordered a taxi.

“I knew from the beginning that these subtle norms seemed to direct us to plan a certain way, a rational way,” Bratman said. “But, pretty quickly, other scholars started asking tough questions: ‘Why do these rationality norms exist in the first place? Why do people worry about having plans that are consistent, coherent and stable?’ And they had a great point. We don’t worry about having consistent wishes or fantasies, for example. I could wish to be a millionaire but also wish not to put a lot of time into earning money.”

Bratman said that his new work is the result of his ongoing effort to explain why these rationality norms exist and why humans should adhere to them.

“The big question is whether having incoherent plans is something we have reason to avoid,” Bratman said. “My conclusion so far is that the answer to that question is ‘yes.’ And that’s because a kind of coherence is not only useful, it is essential to our self-governance.”

Being able to articulate a useful theory for understanding how norms of rationality and human action are interconnected has implications for other disciplines, Bratman said.

For example, in law, Bratman’s idea about the norm of stability could be relevant when explaining why today’s judges place value on previously decided cases, or precedents, when considering future similar lawsuits.

When courts examine whether to reverse themselves on particular issues, a public debate usually ensues over how much significance and power previous decisions should have over the present matters.

“In those discussions and others, the foundational perspective that the philosophical approach can provide us can be invaluable,” Bratman said.

Media Contacts

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: (650) 497-4419, ashashkevich@stanford.edu