In 1962, a group of Mexican migrants in Los Angeles wanted to raise money to help the elderly in their mutual hometown of Guadalupe Victoria, a small rancho in north central Mexico.

The migrants formed Club Social Guadalupe Victoria. Over the next two decades, they provided funds to build a clinic, fence a school, set up electric power lines, provide drinkable water and restore a church.

In an article recently published in the Journal of American History, Stanford Assistant Professor of history Ana Raquel Minian examined how groups like Club Social Guadalupe Victoria developed and managed to transform entire towns in Mexico between the 1960s and 1980s.

Today, there are hundreds of Mexican clubs and associations in the United States and they have attained significant political power in jurisdictions throughout Mexico.

“Immigrants are often imagined to lose touch with their communities,” said Minian, who is also an affiliated faculty member at the Center for Comparative Studies in Race & Ethnicity. “But they maintained strong connections with their hometowns and built a vibrant community life across borders.”

Activist investors

Mexican migrants and U.S.-born Mexicans have formed mutual aid societies since the 19th century. But it wasn’t until the 1960s, an era of high activism throughout the United States, that migrants, primarily in East Los Angeles, began forming groups that prioritized aiding their hometowns.

The Club Social San Vicente’s logo from 1967 reads, in English, “The effort for the good of our people.” (Image credit: Courtesy La Casa del Mexicano, Los Angeles)

The Club Social Guadalupe Victoria began raising funds through small parties and picnics, collecting between $200 and $1,000 per event, according to Minian’s research.

Migrants from other Mexican communities heard about the club and formed their own groups. By the late 1960s, at least 20 clubs began meeting in Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights neighborhood, Minian said. Hundreds of people attended each fundraising party. Club representatives in Mexico distributed the raised funds to the needy.

The clubs fostered an inclusive environment, mixing people from different socioeconomic backgrounds and blurring the lines between documented and undocumented workers.

“Migrants’ capacity to organize themselves and to send resources to Mexico allowed them to build a new and robust movement of transnational welfare activism,” Minian wrote. “Through their activities, clubs took on some of the responsibilities of the Mexican government, becoming a kind of extraterritorial welfare state.”

Influencing government

The migrants’ efforts met challenges from Mexican officials at all levels of government. Local municipalities, in some cases, worked with clubs to fund certain projects, but the state and federal government largely ignored the migrants and corrupt officials demanded bribes from them for transporting aid across borders.

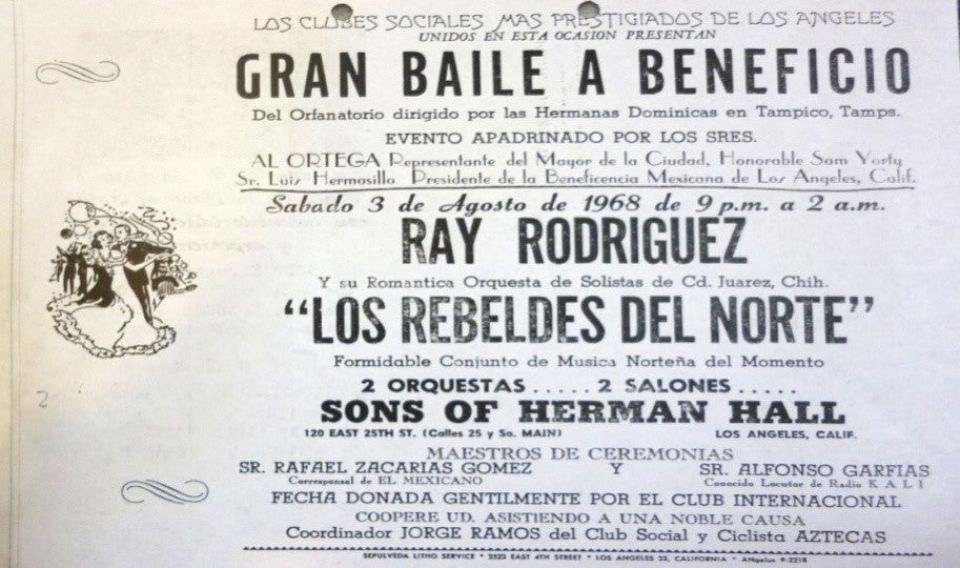

This poster advertised a benefit dance organized by various social clubs in Los Angeles in the summer of 1968. (Image credit: Courtesy La Casa del Mexicano, Los Angeles)

Over time, however, the social clubs managed to gain much influence and respect among Mexican residents, which allowed them to exert pressure on the Mexican government.

“By the mid-1980s, migrants’ investments in Mexico were impossible to overlook,” Minian said.

Mexican politicians began to take advantage of the clubs’ influence. For example, in 1986, Genaro Borrego Estrada became governor of Zacatecas state and sought support from migrant clubs in Los Angeles in order to increase his popularity. He then developed a program by which the state government would match every dollar that migrants sent to Zacatecas to better their communities.

Today, the Mexican government gives three dollars for every dollar migrants donate and influences how the funds are invested.

Exploring the development of these clubs is difficult, Minian said, because neither migrants nor the communities they helped kept all their historical records. But Minian managed to locate archives stored in closets in La Casa del Mexicano, a cultural center in Boyle Heights, where club organizers originally met.

Minian spent several months traveling by bus through several small towns in Zacatecas before she tracked down Gregorio Castillas, a co-founder of the Club Social Guadalupe Victoria. She conducted an oral history interview with him as well as with other migrants who had been a part of the club world.

“This work counters the portrayal of Mexicans as always desirous of coming to the United States and using its welfare coffers,” Minian said. “In fact, migrants refrained from using state resources. Instead, they created their own welfare organizations and sent money back home so that other Mexicans did not have to migrate. They ultimately hoped to be able to return and lead economically secure lives in Mexico.”

Media Contacts

Alex Shashkevich, Stanford News Service: (650) 497-4419, ashashkevich@stanford.edu