A recent Biodesign Innovation class got off to an unusual start. Instead of asking students to pull out their laptops and listen to a lecture, organizers handed out envelopes assigning students to mysterious roles as a patient, caregiver or observer. Then, the students left grad school behind.

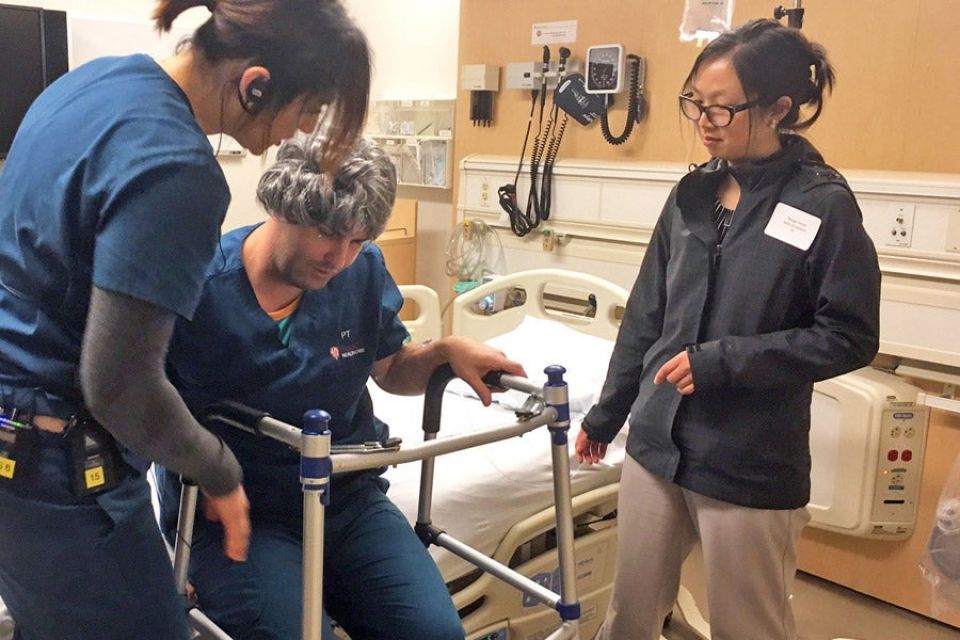

Kiely Schmidt, neurological clinical specialist, left, coaches a simulated “patient” in the post-fall rehab session while his “wife” looks on. (Image credit: Caitlin Ploch)

For the next hour, the students immersed themselves in chaotic, sometimes wrenching hospital scenarios that included an emergency room; a quiet patient room where a woman lay dying; and physical therapy consultation with an ornery fall victim. As each simulation played out, the students struggled to obtain appropriate care and make critical medical decisions against a frustrating backdrop of financial limitations, overburdened providers and conflicting family wishes.

The purpose of the unsettling exercise? To give students in this class, which focuses on developing medical devices and other technology-based solutions to problems in health care, a chance to observe problems in health care delivery firsthand. According to the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign, this is an essential first step for innovators hoping to invent viable technology solutions that fully address an unmet need.

Learning what the needs are

Karla Schroeder, director of palliative medicine and geriatrics (in white coat), tries to help simulated family members reach consensus around care for their dying mother. (Image credit: Alex Gorham)

The philosophy of deeply understanding a problem before trying to invent a solution to address it is at the heart of how the Biodesign Center teaches students at all levels. This method, called a needs-driven approach, requires an innovator to delve deeply into a medical need, including understanding what characteristics a solution must have to satisfy the various stakeholders. Then, those criteria guide the development of a solution. This approach avoids the pitfalls of developing a technology that isn’t marketable or won’t be adopted. As an example, if a technology works but would be too expensive, a hospital may not buy it and the technology won’t reach patients.

The doctors and engineers who participate in Biodesign’s year-long fellowship programs reach this level of understanding by spending upwards of a month immersed in hospitals and other care settings, watching procedures and asking questions. However, graduate and undergraduate students in introductory courses like Biodesign Innovation generally can’t experience this real-world “needs finding” because of time constraints and issues around hospital privacy and compliance. That’s a problem this simulation was meant to address.

Simulations replicate reality

The idea of using Stanford Medicine’s Center for Immersive and Simulation-Based Learning (CISL) to replicate this experience was the brainchild of Denend and emergency room doctor Alexei Wagner. To bring the project to life, the pair worked closely with an entire team of clinical and educational specialists, including Karla Schroeder, director of palliative medicine and geriatrics; Kiely Schmidt, neurological clinical specialist; Susan Eller, CISL assistant dean; and Alexandra Buchanan, CISL director.

“Training innovators is a new endeavor for CISL,” Buchanan said. The center is typically used to give medical students, residents, attending physicians and other allied health professionals the opportunity to practice and improve their skills in a safe but realistic environment.

Wagner designed the three detailed simulations that the students experienced. Each featured real doctors and nurses, high-tech mannequin patients with voices controlled by simulation staff, standardized patients (actors trained to play specific roles) and, most important, real problems in care delivery. Each scenario depicted health care needs related to aging, which was the focus of this year’s class.

Tom Gildea, right, chief resident in emergency medicine, discusses treatment options with simulated student “children” whose “mother” has injured her hip in a fall. (Image credit: Melanie Ester)

The first scenario was a multiple bed emergency room. In one bed, a group of student “family members” was charged with finding appropriate care for their mother, who was in a lot of pain after a bad fall but had limited finances and poor insurance coverage. In another bed, a female patient complained repeatedly that it hurt to breathe, alarming her anxious student caregivers who sought pain medicine and a definitive diagnosis. With all five patient beds filled, the ER realistically conveyed the chaos and frustration that develop as families seek information and reassurance while the ER staff triage their attention in order to deal with competing priorities.

The second scenario involved palliative care. In a quiet patient room, a frail, elderly woman moaned softly as her doctor struggled to reconcile the divergent end-of-life wishes and conflicting priorities of her extended family. In the third scenario, a physical therapy consult, a wife wrestled with the decision of whether she could continue to provide home care for her husband, a large man with compromised mobility, after a debilitating fall.

Chaotic, complicated, humbling

At the completion of each simulation, the students debriefed with the doctors and simulation staff to share their insights and observations. When asked to summarize the experience in a single word, they offered responses such as “chaotic,” “complicated” and “humbling.”

“If you’ve never had the chance to observe health care in this way,” Wagner said, “the experience can be a little overwhelming. But giving them this kind of first-hand experience, even in a simulated environment, is a great way to inspire students about the role they can play in helping make the care experience better for patients and the providers who serve them.”

In fact, the students were so moved that many of them chose projects linked to the simulated scenarios they observed. For instance, one team, concerned with repeat falls in the elderly, is designing an assistive walking device that improves mobility and balance. Another is working on a faster and more effective way to treat skin tears in the elderly when they seek care in the emergency room. A third team is developing a creative solution to improve fine motor function in post-stroke seniors to help restore their independence.