While the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini is best known for overthrowing the last Shah and starting an Islamic Republic in 1979, few realize his significance as a revolutionary poet – and an ironic one at that.

“Khomeini, of whom we have an idea of a political leader and harsh jurist, did write poems that most people – both his supporters and critics – did not expect him to write,” said Ahoo Najafian, a Stanford doctoral student in religious studies.

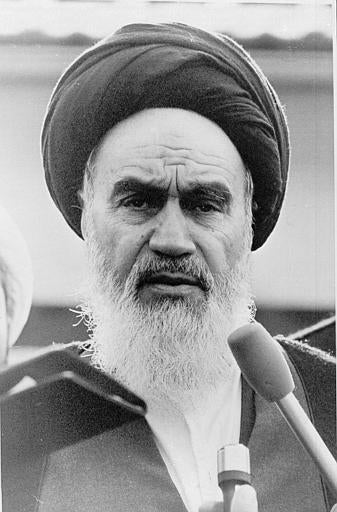

Stanford religious studies scholar Ahoo Najafian says the poems of Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, seem surprising given his theocratic agenda. (Image credit: AP Photo)

In fact, as Najafian discovered, Khomeini wrote about 300 poems. Many of those poems became available in 1989, when Khomeini’s daughter-in-law published his poems posthumously. Najafian has produced the first English translations of some of his poems.

Najafian’s dissertation, provisionally titled “Poetic Nation: Iranian Soul, Poetic Identity, Historical Continuity,” explores how modern poets imitated classical forms in order to represent the present moment. She devotes a full chapter to Khomeini’s poetry.

According to Najafian, Khomeini’s poems seem unorthodox and surprising given his theocratic agenda. “They are against established religion, they are against established religiosity, against political Islam, against teaching Islam and against the seminary,” she said.

But, at the same time, he is following the conventions of a classical poetic genre, one of whose characteristics is antinomian themes, she said.

“I am not trying to lionize Khomeini or criticize him, I just want to show another aspect of him that has been ignored,” Najafian said.

She suggests that “it is time to actually look back at Khomeini and back at what was happening around the time of the Iranian Revolution by people of my generation.”

Rebel poets

Najafian’s research examines the role of poetry in the Iranian Revolution. The modern and contemporary poets that she studies appropriate a much older genre of Persian poetry called ghazal.

As she explained, ghazal grew out of panegyrics, or poems that praised the patron. Recited in Muslim courts as early as the 10th century, these poems typically began by expressing the beauty of nature. As the genre developed, the springtime motif transitioned into a celebration of wine, she said.

Throughout the medieval period, ghazal poems were also commissioned by religious leaders and mystics. In a religious context, Najafian said, “wine comes to symbolize being lost in God, a kind of heavenly intoxication.”

Since these poems were often performed during wine-drinking sessions, the wine represented the glory of the court.

“Wine drinking was an important factor in Muslim courts,” Najafian said, “and the poets go into all these details on why it is not forbidden to drink wine in this situation.”

Given its diverse patronage, ghazal grew into various sub-genres and flourished until the turn of the century. Despite the modern context, contemporary poets are using the same imagery, formats and meters as their classical predecessors.

Khomeini’s poems also incorporate wine imagery, she pointed out.

During the Iranian Revolution, Persian literature, including ghazal, became politically encoded and was used as political agenda, she said.

“So the beloved, for instance, which in the classical ghazal could be read as a man, a woman or the divine, in modern times becomes Iran, the nation,” said Najafian.

“If we are looking at modernity in Iran, we should look at these marginalized genres, and how and why poets are using them,” she said.

Najafian argues that Khomeini’s poetic identity helps create a more complex idea of Islam. Instead of reinstating the stark binary between good Islam (mysticism) and bad Islam (political Islam), Khomeini was a figure who had both elements.

“He was a ghazal writer,” she said.

For example, she pointed to a 1984 poem by Khomeini that combines these seemingly diametric elements:

Oh Saqi! Fill my cup with wine,

So that it purges my soul from longing after fame.

Pour me the wine that annihilates me,

Destroys my chains, my lies.

Give me the wine that frees me from myself,

Loosens my reins, ruins my fame.

Give me the wine that in the haven of the libertines,

Wrecks my prostration, ravages my standing.

In the pure sanctuary of the Tavern’s flower-faced,

From every corner a flower comes to hold my rein.

I go among the bewildered elders, so that,

Their wine frees me of my crude thoughts.

Oh messenger of the light-burdened of the annihilation Sea,

Deliver my praise to the seafarer of that land:

“I ended my nonsensical letter with the ink of wine.”

Tell the Magian Elder to see my happy ending.

Najafian said, “Why would we believe his political writings and juristic writings, but not his poems? There is something going on with literature, truth and language.”

In addition to Khomeini, she considers contemporary ghazal poets who are communists and feminists. For example, she has researched Sayeh, an atheist communist.

For Najafian, it is very interesting that a communist would choose to compose a ghazal.

“We expect a communist to write a social realist novel,” Najafian said, “but he is writing ghazals, and is claiming that this is his manifesto.”

New nation of poetry

Paradoxically, when Khomeini and his contemporaries were writing ghazals, Iranian literary critics devalued the ghazal in favor of newer poetic forms.

These critics, Najafian said, “believe that the contemporary ghazal is not good enough to be studied at all. And if we want to know more about contemporary Iran, we should study New Poetry.”

New Poetry, or modern Persian poetry, evolved out of an attempt to reform Persian literature, beginning in the 1930s, she said. During this period, critics created a literary canon for Iran. They decided that only classical, not contemporary, ghazals belong in the canon.

“There are many manifestos against the ghazal,” Najafian said, “and why we should not read them, and these are the reasons for our backwardness.”

According to the Stanford scholar, literary critics claim “in order to become modern, we have to modernize poetry and the language. So this is the reason they are fighting against the ghazal.”

Yet, the most rebellious of Iranians continued to compose ghazals. “One of the reasons why I am doing this is because there hasn’t been any study of contemporary Persian ghazal,” she said.

Media Contacts

Chris Kark, Director of Humanities Communications: (650) 724-8156, ckark@stanford.edu

Clifton B. Parker, University Communications: (650) 725-0224, cbparker@stanford.edu