If you were checking the schedule for the X-ray facilities in the McCullough Building at Stanford University last October, you would have seen one hour reserved for the “Metalheads.” No, not a heavy metal band – although not totally unrelated – these metal enthusiasts were students of “Metalheads of Modern Science,” a course that employed X-rays to characterize the chemical makeup of ancient coins from the Stanford Libraries collection.

The X-ray diffractometer analyzing an ancient coin. This equipment provides information about the crystal structure of an object – and therefore its chemical composition – through measuring how X-rays move through and around the object. (Image credit: Andrew Brodhead)

The course, created and taught by new materials science faculty member, Leora Dresselhaus-Marais, is designed to give first-year students a broad understanding of what materials science is as a field and what one might do with a materials science and engineering degree. Along the way, it also provides guidance about applying to internships and jobs. The class aspires to be an accessible, supportive, engaging introduction to an area of science that many students haven’t heard of before.

“I wanted to create a class where, from day one, we show students where material science exists in our lives, where we’ve always used it but we never knew,” said Dresselhaus-Marais, who is an assistant professor of materials science and engineering. “This class is everything that drew me to becoming a professor and I love going to class every day.”

The course title originated from Dresselhaus-Marais’s husband’s efforts to get her back into heavy metal music. When Dresselhaus-Marais explained that she’d moved on from that scene, he pointed out that she – an expert in metals and other solid materials – was perhaps the biggest “metalhead” of all. “It was the perfect name for the course,” said Dresselhaus-Marais, who found it hit the right note of fun and approachability.

Metals through time and space

Students in the course this fall explored foundational concepts of metals materials science by embarking on a journey that started with ancient metallurgy and ended with modern applications of materials – from long-range space travel to sustainable mining and metals in geology and in health care.

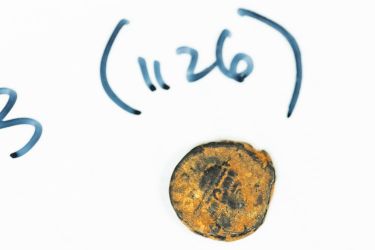

When a speaker canceled on short notice early in the quarter, Dresselhaus-Marais and her course assistant, materials science graduate student Evan Carlson, threw together the coin lab with help from Glynn Edwards, Regina Lee Roberts and Kathleen Smith from Stanford Libraries and Arturas Vailionis, director of the X-ray lab at the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities. That lab focused on coins in the collection that are less well-preserved and that have little information known about them. With just one scan, the class observed a surprising amount of silica in one coin, implying that it might have spent considerable time buried in sand.

Students responded so enthusiastically to that X-ray investigation that Dresselhaus-Marais and Carlson reworked their lesson plans to include additional hands-on experiences with metal 3D printing and a visit to the Stanford mineralogy collection.

“It’s nice to see students get really excited,” said Carlson. “You can see on their faces that they’re really engaged with the material, and that’s rewarding.”

Carlson and Dresselhaus-Marais are also especially proud of the Metalheads Coffee Hour, which gave the students an opportunity to stay after class and chat with the speakers.

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Andrew Brodhead

Image credit: Leora Dresselhaus-Marais

Image credit: Leora Dresselhaus-Marais

Becoming a materials scientist

Dresselhaus-Marais officially joined the world of materials science rather recently. She first learned about the field in graduate school, where she studied physical chemistry before embarking on a physics postdoc. In the end, materials science – and specifically materials science and engineering – was the right fit for her research interests because she liked its grounding in understanding and controlling real-world processes.

In hopes of giving current students an earlier introduction to this field than she had, Dresselhaus-Marais asked the class speakers to spend some time discussing their own career journeys. This helped inform the class’s final project, where groups of students presented about a specific job that could follow a materials science degree. These presentations included jobs in academia, startups and national labs, as well as less conventional paths like policy, government, law or philanthropy. Students also wrote a job description for their presentation subject, to help them see concretely what skillsets are sought for candidates suited for such work.

The aim of this assignment was to encourage students to develop a clear, realistic understanding of careers in materials science and the steps needed to land one.

“One of the things that you always see in diversity, equity and inclusion studies is that with each successive step through a career path, you lose more and more people from underrepresented groups – such as first-generation college students, women in science and other underrepresented minorities,” said Dresselhaus-Marais. “This is because they aren’t given any clear direction or trajectory, and it’s hard to find mentors who can show them the way.”

Although unintentional, Dresselhaus-Marais notes that every student who was in Metalheads last quarter would be considered an underrepresented minority (URM) in the field of materials science, and 80 percent of the class were women. She has a theory for why that might be.

“I think this course fills a need that often causes URMs to not see STEM careers as a viable path – as they may not have role models or family who they can ask about the process,” Dresselhaus-Marais said. “Studies have demonstrated that one reason that URMs often leave science originates from a lack of understanding the steps for how to move forward on the career path, and this course focuses specifically on that.”

The last piece of the final project was a resume. Originally, Dresselhaus-Marais was going to have students craft a resume in answer to their job description, but Carlson suggested that the students should instead write a resume for themselves to apply to the Stanford MatSci (Materials Science) Research Experiences for Undergraduates Program. Students don’t have to actually apply but having a polished resume in hand that is designed for a “first research project” can remove a barrier that might otherwise prevent them from trying.

“It’s been really awesome getting a chance to help people find square one,” said Dresselhaus-Marais. “Then we explain to them how once you get to square one, you always have some non-zero experience to build on; the only thing that is required to get to that point is to start applying.”

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.