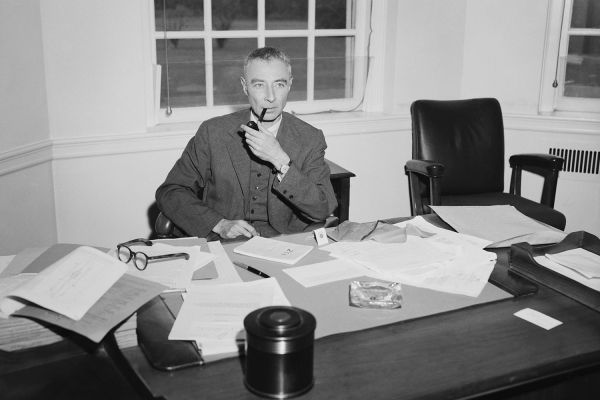

Christopher Nolan’s biopic about the American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s efforts to build the world’s first nuclear weapon has been a box office hit, drawing in audiences curious to see the controversial and tragic story of the man known as “the father of the atomic bomb.”

J. Robert Oppenheimer, considered the father of the atomic bomb, is the subject of a new film by Christopher Nolan. Oppenheimer was director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico where the development and first nuclear test took place. (Image credit: Getty Images)

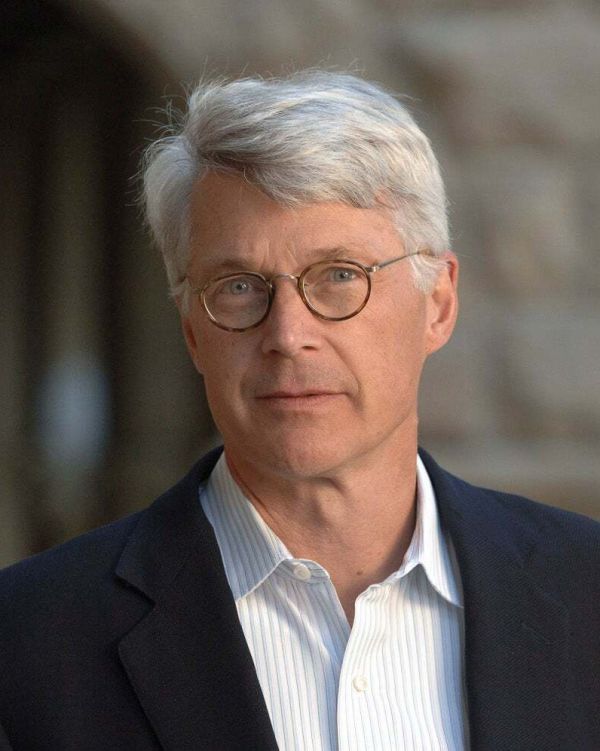

Seeing Oppenheimer on opening weekend was Stanford scholar and political scientist, Scott Sagan. As co-director of Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC), Sagan had a professional interest in the movie about the United States’ scramble to build the first nuclear weapon before Germany did, and he was already very familiar with the story of the film’s main character, which is played by actor Cillian Murphy.

Here, Sagan talks with Stanford Report about what he thought the film captured well – and not so well – about the politics of nuclear proliferation, Oppenheimer’s attempts after World War II to constrain the new military technology, and the frightening role nuclear weapons play today, including the threats Russia has made in the ongoing war in Ukraine.

“I hope the film really gets people interested in thinking through better ways of managing nuclear technology, in addition to other dangerous technologies,” said Sagan. “That’s going to be a big question for the United States in the future. And we need great minds of the next generation, future Oppenheimers if you will, to help us all deal with that problem.”

Sagan is also the Caroline S.G. Munro Professor of Political Science in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

The interview may contain movie spoilers.

What were some of your takeaways from the film?

First of all, I thought for a Hollywood movie, it was highly accurate and very moving. The book the film is based on, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of Oppenheimer, showed Oppenheimer’s triumphs of creating a scientific community at Los Alamos and building the first atomic bomb in less than three years, a remarkable achievement that perhaps no one else could have pulled off. There are two tragedies, one, the personal tragedy for Oppenheimer of having the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) take away his security clearance in 1954, a public humiliation that ended his relationship with the U.S. government. It was only in 2022, 55 years after Oppenheimer’s death, that Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm reversed that decision, citing “the bias and unfairness of the process that Dr. Oppenheimer was subjected to.”

But I think there’s a broader tragedy that came out less clearly in the movie: the political tragedy of the nuclear arms race that emerged between the Soviet Union and the U.S. in the 1950s, which Oppenheimer tried unsuccessfully to constrain through proposing early cooperative measures with Moscow, efforts that would only much later materialize through the arms control treaties like the Limited Test Ban Treaty in the 1960s and Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty in the 1970s. We do not know whether the Soviet Union and the U.S. could have negotiated mutually acceptable national security arrangements earlier, but we do know that the U.S. government never really tried.

In the film, AEC commissioner Lewis Strauss wanted Oppenheimer’s security clearance taken away for personal reasons. But as you indicate, politics were at play as well. What did you make of that portrayal?

I think the film overemphasized Lewis Strauss as having a personal vendetta against Oppenheimer, who had publicly ridiculed Strauss’ lack of scientific expertise, which was true. But that was not the only reason why Strauss wanted to diminish Oppenheimer’s influence in Washington. This was also a political fight, one between a liberal scientist wanting to prevent an arms race and a conservative political actor wanting to win one. Oppenheimer was by no means a pacifist, he fully supported having a strong U.S. arsenal – he just didn’t want to develop the hydrogen bomb. Revoking his security clearance was a way of reducing his effectiveness in private and public debates that were going on in the United States. It discredited him, and therefore, indirectly discredited some of the valuable ideas he had. And that makes the story even more tragic.

Was there a scene in the film that stood out to you the most, and why?

There was a scene in which Oppenheimer, wearing a military uniform, tells fellow Los Alamos physicist Isidor Rabi that all the scientists in the Manhattan Project were expected to enlist in the U.S. Army. Rabi tells him to refuse and to let the scientists be independent civilians. “You should be yourself, but only better.”

To me, Oppenheimer taking off his uniform is a metaphor for the need in any scientific endeavor to have diversity of ideas and spurts of creativity that come from individuals being in a completely collective enterprise that still does not stifle diverse opinions. Oppenheimer understood that this was crucial for development of the bomb. I think that’s true more broadly in dealing with the problem of nuclear weapons and the pursuit of disarmament today: You need diversity of opinion and multiple disciplines working together. The security studies field is weakened when everyone puts on the same uniform.

How can scholars and scientists balance moral and ethical dilemmas that can potentially arise in the application of their work?

When Oppenheimer refused to sign the letter that Leo Szilard, the physicist who created the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, and others wrote opposing dropping the bomb on Japan, Oppenheimer said that the scientists who invented the atomic bomb have no greater rights or responsibilities than others about how to use the weapon. I disagree with that. I think scientists and social scientists who have expertise in this area have grave responsibilities to express their opinions about nuclear strategy, and how we respond could be used in a war or used for deterrence. I think there can be worrisome tendencies for scholars to fall in line with what is the current rage or received wisdom about what the best national security policy should be. We’ve got to constantly challenge the status quo and think carefully about alternative policies.

What do you think Oppenheimer would make of the threats nuclear weapons pose today?

I think he would view it as a great tragedy in the making.

The United States and the former Soviet Union were able to come to very important arms control agreements, but only one is in place now – the New START Treaty which the U.S. and Russia entered into in 2011 – and that’s going to expire in 2026.

What I thought the film did quite well was portray the naivete of some American officials, including President Harry Truman, who thought the Soviet Union was not going to get nuclear weapons for a long time, if ever. That belief was just scientifically naïve, and Oppenheimer showed himself to be absolutely correct.

There is also a frightening role nuclear weapons are playing in the war in Ukraine today. Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly threatened the use of nuclear weapons, most dramatically when he annexed portions of Ukrainian territory and said that when the United States used nuclear weapons against Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it set a precedent. Putin was threatening that the Russians might use nuclear weapons against Ukraine as a way of trying to end the war. I hope someone reminded Putin that the Japanese couldn’t strike back at the U.S. in 1945. Today, Ukraine could strike back at Russia and the U.S. can help ensure an effective response.

The film touched on the use of nuclear weapons as deterrence, the idea that an enemy attack is avoided by a credible threat of devastating retaliation. Can you explain this strategy and what risks it poses?

There are many who believe nuclear deterrence is infallible – that the threat of nuclear war has been so strong that it’s led all states that acquired the weapon to be equally deterred and therefore, that the pursuit of arms control and disarmament are not necessary. But I think that’s a false belief.

Nuclear weapons are not controlled by abstract entities called states; They are controlled by normal human beings in complex and imperfect organizations that make mistakes. The risk of nuclear use is not only that a desperate leader, like Putin, might use nuclear weapons for political purposes; there’s also a danger of a weapon being used by accident, through a miscommunication, or through a false warning that an attack was underway.

What message do you hope people will take away from the film, particularly those who did not live through the Cold War and are unfamiliar with the fear of nuclear war that persisted throughout this time period?

Broadly, for the younger generation, I think there has been a loss of interest in nuclear nonproliferation, in part because of other concerns – e.g. runaway AI, climate change, pandemics – that have led some to think that nuclear weapons are not an existential threat. I hope the film really gets people interested in thinking through better ways of managing nuclear technology, in addition to other dangerous technologies.

Is there anything to be optimistic about?

Thankfully, since the end of the Cold War, arms agreements have reduced the number of weapons in the U.S. and Russian arsenals by tens of thousands. Today, we have a cap of 1,550 weapons in each state’s deployed arsenal. But there are going to be pressures to increase that with China building up its nuclear arsenal now. Maintaining stable, deterrent relations with both Russia and China is going to be a huge challenge for the United States. There are some who argue that the U.S. needs to build its arsenal to have at least equal numbers with both Russia and China, which means we’ll have more than either of them. Which they, of course, will resist. Can we find a path to arms control or is a three-way arms race inevitable? That’s going to be a big question for the United States in the future. And we need great minds of the next generation, future Oppenheimers if you will, to help us all deal with that problem.