It happens all too often: You log on to social media for a fun break, but you find yourself riled up and angry an hour later. Why does this keep happening?

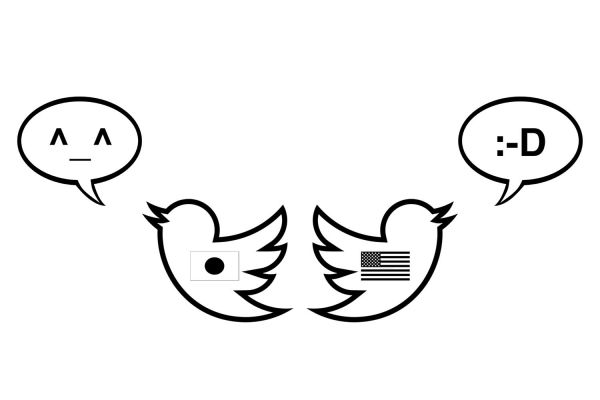

A Stanford study of Tweets by Japanese and U.S. Twitter users reveals how cultural differences in emotions influence what goes viral on Twitter. (Image credit: Brian Knutson)

New research by Stanford University psychology Professors Jeanne Tsai and Brian Knutson and their team suggests a key piece of the puzzle involves culture. In a new study, published online Sept. 7 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the team assessed the emotional content, called “sentiment,” of Twitter posts by Japanese and U.S. users, and found that users were more likely to be influenced by others’ posts when the posts violated, rather than supported, their cultural values.

Cultural nuances

Though social media spans the globe, current studies disproportionately focus on users in the United States, rather than users from non-Western contexts.

“It just felt for me that a piece is missing if you don’t consider culture,” said lead author and graduate student Tiffany Hsu. “Culture is such an important aspect in terms of social media and connecting people.”

In the U.S., for example, most people state that they like to feel excited, happy and positive. Yet, previous research has found that U.S. social media users are most influenced by posts that express anger, rage and other negative emotions. What can explain this paradox?

To try to find out, the Stanford researchers turned to social media users in a non-Western country, specifically Japan. Research has shown that Japanese people generally value different affects (emotions) which are lower in arousal (e.g., calm, equanimity) than people in the United States.

In order to test whether Japanese users would also be more influenced by social media posts that violated their values, the team developed a sentiment analysis algorithm that could be applied to both American and Japanese content.

It wasn’t an easy feat to build this technology from the ground up: The team used machine learning based on manually coded labels from 3,481 Japanese Tweets to make it work. The program was based on SentiStrength, which scored short English text by positivity and negativity, as well as its emotional intensity/arousal. The researchers created a similar algorithm for Japanese text.

The researchers found that, in general, social media users in the U.S. produce more positive content (e.g., The cutest pictures are from Kindergarten graduation!😍❤) on social media, while users in Japan produce more low-arousal content (e.g., Another week of exams then I’m sorta free 🏀😒), consistent with their respective cultural values. These results extended across different topics, including personal issues, entertainment and politics.

“Left to their own devices, social media users seemed to produce culturally valued content,” said Knutson, a professor of psychology in the School of Humanities and Sciences (H&S).

However, the opposite seemed to apply after users had been exposed to others’ posts.

“Users seemed to be most influenced by others’ posts when those posts contained feelings that violated their cultural values,” explained Tsai, the Yumi and Yasunori Kaneko Family University Fellow in Undergraduate Education in H&S and the director of the Stanford Culture and Emotion Lab. “So for the U.S., users are most influenced by others’ high arousal negative content like anger and disgust, but for Japan, users are most influenced by others’ high arousal positive states like excitement.”

The team has dubbed this phenomenon “affective hijacking” – in which exposure to content that violates users’ cultural values temporarily redirects their own content.

Implications

The source of the affectively disruptive content is not yet clear, but the fact that it is often accompanied by propaganda or misinformation suggests that it could come from nefarious actors or even algorithms, according to the researchers. Regardless of the source, the fact that the disruptive content can be measured implies that tools might be developed to help users identify the disruptive affective content.

“Self-control is great but limited,” Knutson said. “Is there some software we could develop for people – just like a spam filter for email – that could help them apply affective filters to their social media? We’re interested in giving people more power to choose what they’re exposed to.”

This research has led the team to work on developing tools that allow social media users to identify posts capable of “hijacking” their emotional experience. Perhaps this could eventually reduce the time that users spend in emotional states that they don’t value while simultaneously minimizing misinformation.

Michael Ko at Stanford University, Yu Niiya at Hosei University and Mike Thelwall at University of Wolverhampton also contributed to this research.

The research was partially supported by the National Science Foundation and the Stanford Human Artificial Intelligence Initiative.

Media Contacts

Holly Alyssa MacCormick, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: hollymac@stanford.edu