Telling the story of the Congo-Océan railroad, one of the deadliest construction projects ever undertaken, was a way for historian J. P. Daughton to remember the tens of thousands of Africans who perished between 1921-34 at the hands of French colonizers intent on completing the ill-conceived project, no matter the cost.

Daughton’s new book, In the Forest of No Joy: The Congo-Océan Railroad and the Tragedy of French Colonialism (Norton, 2021), captures the gravity of this tragic story that’s still largely unknown amongst the general public. The government of France, which prided itself on its humanitarianism and liberalism, allowed and documented the deaths of thousands of African men, women and children, Daughton said. At least 20,000 people are believed to have perished in the building of the railroad.

“The people who built the railroad underwent horrific treatment and extraordinary suffering,” said Daughton, associate professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “Their stories need to be told.”

Forest of no joy

In the years following the end of World War I, the Societé de construction des Batignolles, one of the largest French engineering firms at the time, began building the Congo-Océan railroad in the southern part of French Equatorial Africa, a region often referred to simply as “the French Congo.”

The project had long been heralded by the colonial government as essential to the economic development of the region by connecting the colony’s largest settlement on the upper Congo River, Brazzaville, to Pointe-Noire, on the Atlantic coast, where the French planned to build a deep-water port.

Covering 318 miles, the railroad crossed difficult terrain including the treacherous Mayombe rainforest, where rails had to be placed on unstable, sandy soil while winding through a region of dense forests, mountains and gorges.

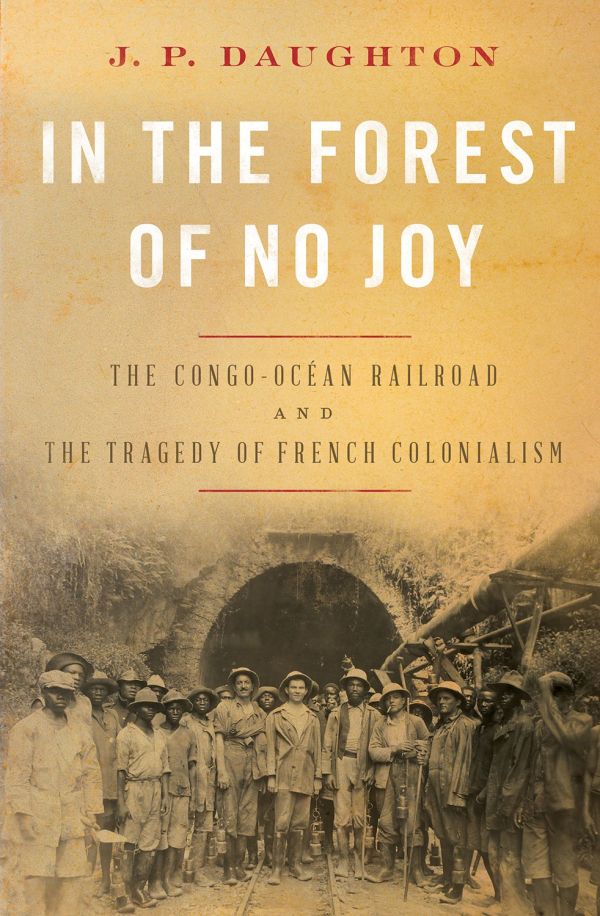

While photos from the period show well-fed, smiling Frenchmen, photos of the unnamed Black workers show malnourished, overworked and under-clothed Africans. The latter were recruited by force and coercion and made to work 10 hours a day, six days a week, without proper allocations of food or medical care.

“The railroad’s brutality was petty, unthinking and often cruel – justified by racist beliefs that conveniently displaced moral responsibility,” said Daughton. The French administrators in the Congo kept records of the death toll of the project. Reports of the large loss of life to the French Parliament resulted in well-known writers of the time traveling to the Congo to report on the situation. They soon wrote scathing reports, criticizing the terrible loss of lives. However, when the French Parliament debated the issue, the government resorted to well-worn tropes of how their efforts were bringing European notions of humanity and civilization to Africa.

Bureaucratic control

“It was understood by colonial officials on the ground that the railroad was a key goal of the French government during this period – a linchpin to develop the colony and to save the lives of Africans who were portrayed in racist ways,” Daughton said. “An entire bureaucratic language developed that never questioned the railroad’s value, denied the very possibility of brutality and shaped the way administrators collected and distorted information.”

At the time, in order to fulfill the mandate of providing a certain number of recruits to work on the project, French recruiters resorted to horrifying violence against communities in an effort to intimidate those who survived into “volunteering” for the railroad project.

As the railroad was built, entire families and communities were torn apart. Many Africans died at the hands of recruiters, or while traveling to work sites located hundreds of miles away. Some Africans fled into the forest to avoid capture, often perishing in the harsh forest conditions. Those that survived suffered the loss of having to leave their families, homes and communities behind.

One man’s story

Personal stories help modern historians understand and convey to the public what life was like under brutal conditions. “We have rich and valuable histories telling us what life in a gulag or concentration camp was like but surprisingly few to tell us about the experiences of African laborers living under European colonialism,” Daughton said.

Drawing on Congolese and French archival records, including documentary records from the construction company and the French government, stories written by prominent writers of the time, accounts of interviews with Africans who survived, medical reports and photographic evidence, Daughton was able to piece together the tragic reality of the situation on the ground. In doing so, he detailed what happened to people who consumed a fraction of their required calories a day, when hundreds of laborers were packed on a small boat and the consequences of not providing adequate hygiene and medical care to workers.

The tragic story of one worker, in particular, stuck with him. “A 30-year-old man named Malemale shows up for a fleeting page in the archives, but in it, you see the way in which the grand machine of empire functions,” Daughton said. Malemale was the husband of Vlapedoum and the son of Batakoudou and Gbaké. He was recruited, likely coerced, to help build the railroad, but the village where he lived was hundreds of miles from the building site.

Through the records, “we see him wasting away as he goes from medical inspection to medical inspection,” Daughton said. At each stop, the French doctors sent him on because they were in need of laborers. When Malemale finally arrived at the railroad construction site, the doctor there saw how emaciated and sick he was and sent him to the hospital. He died a day or two later.

“Stories like Malemale’s are the stories of empire that don’t get told,” Daughton said. For some people, “it’s comforting to believe that hateful madmen made empires violent. In fact, the negligence, denial and assertions of humanity by colonial officials and by national governments, in pursuit of ‘progress,’ often proved far more cruel.”

Media Contacts

Holly Alyssa MacCormick, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: hollymac@stanford.edu