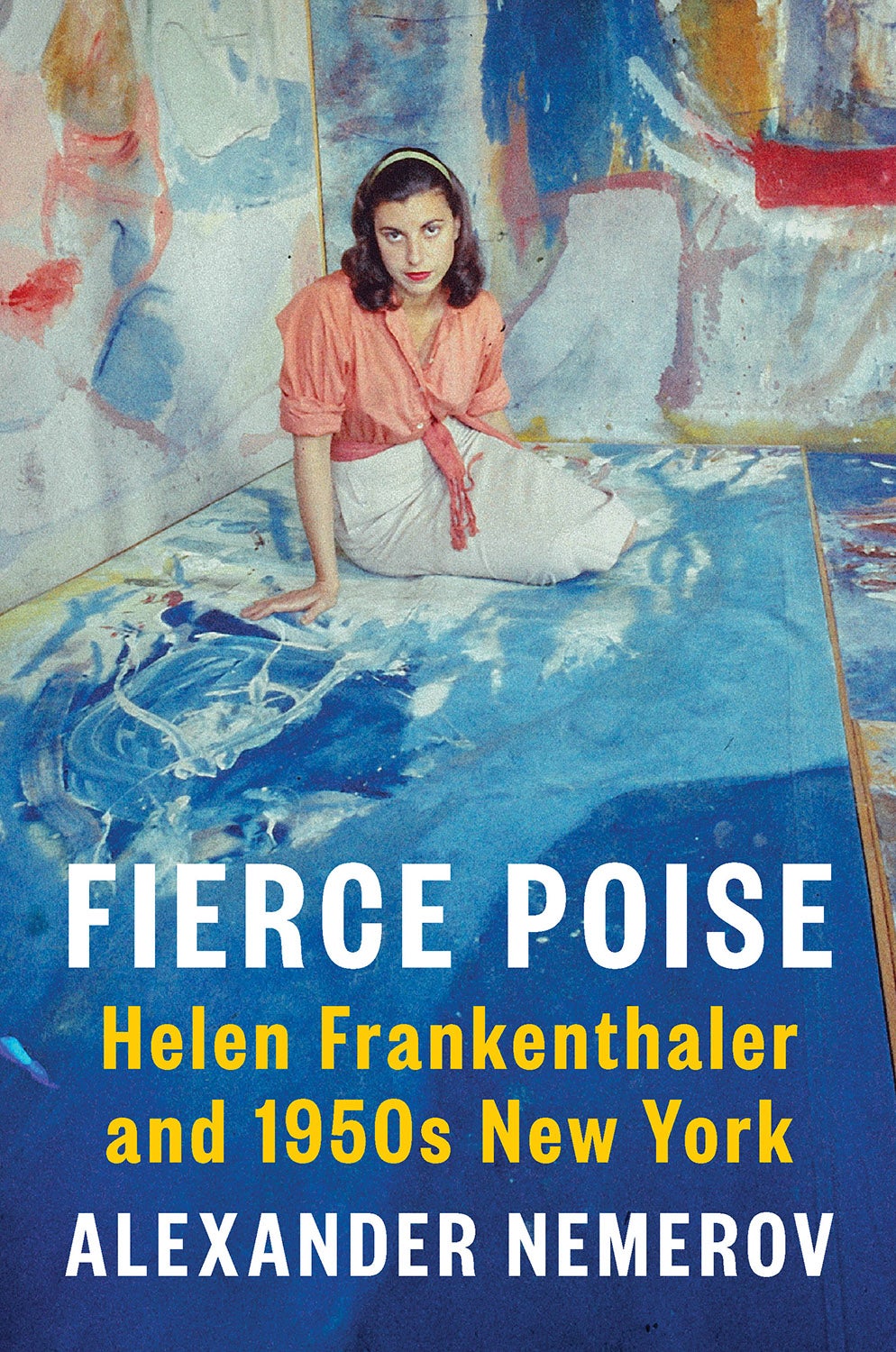

The “electric aliveness” of artist Helen Frankenthaler’s work is conveyed in a new biography, Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York (Penguin Press), by Stanford art historian Alexander Nemerov. “The day portrayed – all the unsung but glorious moments that make up a day on Earth – that’s what her work really gets at,” Nemerov said, reflecting on what drew him to the abstract expressionist’s work.

Mountains and Sea, 1952, painted when Helen Frankenthaler was 23 years old, was her first professionally exhibited work. Collection Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York, on extended loan to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. © 2020 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. (Image credit: Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Nemerov, the Carl and Marilynn Thoma Provostial Professor in the Arts and Humanities in the School of Humanities and Sciences, said he appreciates the bold colors, fluid movement and lightness of feeling Frankenthaler achieved in her 20s. During that time, she was a part of the New York art scene that included luminaries like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning.

Fierce Poise traces Frankenthaler’s early career, beginning in 1950 when after having graduated from Bennington College in Vermont, Frankenthaler moved home to New York City to begin making a name for herself in the male-dominated art world. The book ends a decade later after Frankenthaler had succeeded in launching a career that would span more than half a century.

Capturing the vibrancy of a day

Nemerov notes that unlike many other artists of the time, Frankenthaler had been raised by a well-to-do family on the Upper East Side. Her father, Alfred Frankenthaler, was a respected judge on the New York State Supreme Court. But even with means, know-how and ambition, Frankenthaler needed a special gift to achieve success.

“That gift consisted in taking what was happening around her – inside her, too – and bringing it out in sudden, momentary pulsations of color and shape and line,” Nemerov writes. “The result was paintings as surprising and glorious as life itself, paintings that enshrine the living feeling of days like no one else’s do.”

And it was that ability to capture the vibrancy of a single day that ultimately inspired the structure of the book. Starting in 1950, Nemerov picked one day in each year of the decade to examine a different part of Frankenthaler’s life and work. The organizational device allows Nemerov to convey both a sense of immediacy and to jump backward and forward in time, introducing the reader to Frankenthaler’s formative years and her art mentors.

“We expect paintings to speak in some kind of internal way, but what Helen does is show the glory of the daily – the impression, the vivid sensation – walking down the street on a winter day in New York in 1953 or being at the seashore,” said Nemerov, who is also chair of the Department of Art and Art History. “She was able to take those sensations and take paint and canvas and render an abstract version of it such that her sensation becomes ours.”

Nemerov’s narrative framework also helped him explore Frankenthaler’s relationships with art luminaries who influenced her, including long-time boyfriend Clement Greenberg, an influential art critic, as well as her eventual husband, the artist Robert Motherwell.

Archival material critical to work

To piece together the artist’s life, Nemerov relied on a wealth of resources. His research includes personal letters spanning five decades, housed at Princeton University, that Frankenthaler wrote to her friend the writer, literary critic and scholar Sonya Rudikoff. Other resources included interviews with the artist herself and other biographical information collected at the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, founded in 2011, the year Frankenthaler died.

“Archives inevitably change your perceptions of the person,” Nemerov said. “A part of the art of scholarship is that fluid give-and-take relationship to the materials you’re discovering and the person they portray.”

Although Nemerov never met the artist, he always felt a personal connection to her. His father, Howard Nemerov, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and former poet laureate of the United States, was an English professor and taught Frankenthaler at Bennington College. The younger Nemerov was born in Bennington, Vermont, in the early 1960s, years after Frankenthaler had left.

While Alexander Nemerov was always moved by Frankenthaler’s paintings and considered writing about her decades ago, he said he knew he wasn’t ready at that time.

He explained his hesitancy by noting that one thing he really envied and admired about Frankenthaler’s work is that, even when she was in her 20s, she was able not only to make great pictures but also to make pictures that capitalize on that feeling of being alive at that age – “the intensity and awareness where everything takes on a miraculous significance,” Nemerov said.

“When I was in my 20s, I saw a lot of that and felt a lot of that, but I didn’t have the means, confidence and wisdom to portray it as it was happening to me in real time,” he added. “I’m grateful that in my 50s I could catch up to Helen.”

While some critics found Frankenthaler’s early work too light in terms of technique and subject, preferring her more stately work from the 1960s, Nemerov said he always found the early work very powerful.

“I think her magic period was at the start. Perhaps that relates again to my praise of her young person’s work – of a person becoming, changing, transforming,” he said. “Frankly, I can’t think of an artist in the whole history of art who has done that better.”

Media Contacts

Joy Leighton, Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences: joy.leighton@stanford.edu