The upcoming centennial of the 19th Amendment is a milestone in women’s suffrage, marking a culmination of decades-long efforts by women who called for full citizenship. This history, Stanford historian Estelle Freedman says, can be traced back to the abolition movement in 19th-century America.

Go to the web site to view the video.

Here, Freedman discusses how the histories of the women’s suffrage movement and abolitionism are closely intertwined: It was through their opposition to slavery that middle-class American women first became politically active, said Freedman. The anti-slavery movement pushed women out of the home and church and into politics, eventually leading some to advocate for their own rights as women.

For example, Freedman shares the stories of Angelina and Sarah Grimké, some of the early white female abolitionists, who noted in 1837 that advocating for the rights of enslaved people inspired them to examine their own role in American political society. Also advocating for women’s rights – particularly the rights of Black women – was the formerly enslaved abolitionist Sojourner Truth.

Estelle Freedman is the Edgar E. Robinson Professor in U.S. History in the School of Humanities and Sciences. (Image credit: Sunny Scott)

Freedman also discusses how the women’s suffrage movement split over race after the Civil War, what it did and did not achieve, and what can be learned from this history.

Freedman is the Edgar E. Robinson Professor in U.S. History in the School of Humanities and Sciences. Her research interests focus on the history of women and social reform, including prison reform, as well as the history of sexuality and sexual violence.

You have written about how anti-slavery activism inspired women’s suffrage. Can you explain how these two movements are connected?

The history of suffrage cannot be separated from the history of race and class in America. The suffrage movement in part had its origins in the anti-slavery movement in the United States.

Anti-slavery activism drew both Black and white northern women into politics during the antebellum period, from the 1830s through the 1850s. While Black women sought freedom for their own race, some white women steeped in religious or moral training came to believe that slavery defied their ideals of womanhood and of justice. Think of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s appeal in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which played to the sentiment northern middle-class women attached to the family by portraying enslaved families sold apart. Abolitionist literature alluded to the rape of enslaved women, which affronted ideals of female purity.

While they found different paths into the small but vocal anti-slavery movement, northern women who joined it moved beyond the limits of the home and church. They formed hundreds of female anti-slavery societies and in the process engaged in politics. Some women merely tried to influence their husbands, sons or brothers – who were voting citizens – but others increasingly took action themselves. For example, during the campaign to send petitions to Congress to abolish slavery, the women’s anti-slavery societies gathered the bulk of the signatures.

When female abolitionists tried to speak in public, however, the public condemned their unladylike behavior. Maria Stewart, a northern Black anti-slavery activist, justified her right to speak out politically, whatever her race or her sex. Angelina and Sarah Grimké, who left a slave-holding family in the South, also chafed under restrictions on their right to speak publicly against the evil of slavery. As Angelina Grimké explained, “The investigation of the rights of slaves has led me to a better understanding of my own.” Sarah Grimké’s Letters on the Equality of the Sexes (1837) articulated an early critique of misogyny, marriage and economic inequality, one considered far too controversial for the time. Both Stewart and the Grimké sisters, however, withdrew from public speaking.

The World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 provides another link between anti-slavery and suffrage. U.S. delegates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott shared the humiliation of having to sit in the balcony as observers (where some male allies joined them). Eight years later, living near Seneca Falls, New York, the two women called together a convention on women’s rights, which the leading abolitionist Frederick Douglass chaired. The subsequent convention movement called for married women’s property rights, access to education and occupations, and woman suffrage.

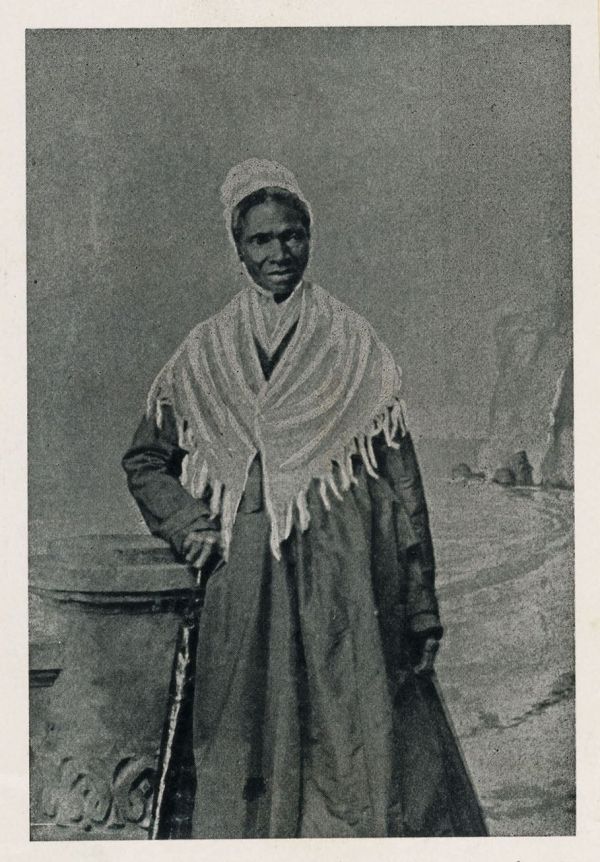

The formerly enslaved abolitionist Sojourner Truth spoke out for the rights of Black women in particular, foreshadowing later concepts of the inseparable intersections of race and gender, said Stanford historian Estelle Freedman. (Image credit: Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection)

What role did Black women play in the abolition movement and how did their efforts help shift perceptions of women’s role in society?

I think a good example, and a link from the antebellum to the post-Civil War suffrage movement, is the formerly enslaved northern woman who chose the name Sojourner Truth when she became an itinerant preacher. Her speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Ohio in 1851 – erroneously remembered as “Ain’t I a woman?” – responded to white male hecklers who claimed that women should stay on their protective pedestal rather than seek to vote. By invoking her own history, Truth exposed the appropriation of women’s reproductive and productive labor under slavery. In effect, she insisted that racism contradicts the protected woman’s sphere – you can’t have both idealized womanhood and racism.

Less well known is Truth’s 1867 speech in which she called for equal rights for both formerly enslaved men and all women. She argued that if the 15th Amendment expanded suffrage only to Black men, it would be “as bad as it was before” emancipation for Black women. In both instances, she articulated the inseparability of race and gender now known as intersectionality.

What led to the separation of these intertwined causes?

Let’s start with the historical context of the Gilded Age of the late 19th century. In the aftermath of the Civil War, industrial capitalism spawned wealth, poverty and intellectual justifications for both, such as social Darwinism, scientific racism and nativism. It was not an era conducive to progressive change. The southern quest to re-establish white supremacy culminated in Jim Crow segregation, the disenfranchisement of Black men and the rule of terror by extralegal lynch mobs. The 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy vs. Ferguson made segregation legal.

Within this context, the small and unpopular suffrage movement faced formidable challenges, including a bitter split among former abolitionists over supporting the 15th Amendment without including women. In the next generation, historians have identified a shift in arguments for suffrage, from an earlier call for justice to a later politics of expediency. How can we get to this end, suffrage? In the context of a racist society, some but not all white suffragists adopted rhetoric asking, “Why are ignorant, illiterate immigrants and Black men voting when educated white women can’t vote?” They also tried to appease southern suffragists by excluding Black women’s groups from national meetings.

I think that many white suffragists did not appreciate the importance of the vote for Black women. Given the disenfranchisement of southern Black men – through mechanisms like literacy tests, grandfather clauses and poll taxes – they may have considered Black women unlikely voters and thus, expendable. Black women, however, understood that they needed the vote even more than most white women, in order to advance their goals of racial justice. While the suffrage movement may have had a wide racist streak, it was not entirely a white women’s movement. Black women joined mixed race groups and formed their own suffrage associations, and leaders like Mary Church Terrell refused to march at the back of the parade when she and other Black suffragists joined white allies in the mainstream.

Ten suffragists were arrested on August 28, 1917, as they picketed the White House. The protesters were there in an effort to pressure President Woodrow Wilson to support the proposed “Anthony amendment” to the Constitution that would guarantee women the right to vote. (Image credit: Stanford Libraries Special Collections)

As we commemorate the milestone of women’s right to vote, what do you want to see in the discussion of this celebration?

We can see it as a great victory, the culmination of decades and decades of effort by women who spoke, wrote and lobbied for the suffrage; who tried to vote, as Susan B. Anthony did in 1872. Whether they claimed that women’s maternal qualities would vote in a better world or, as younger self-identified feminists insisted, that women were no different than men, they eventually won over male legislators. We can see the 19th Amendment as a benchmark in the long movement for full citizenship for women, a major political hurdle passed. We can also see it as a limited victory, given the continued disenfranchisement of southern Black and Native American women at the time. But I think we can’t make it into the endpoint of a historical “wave.”

“Suffrage had the potential to enable political change by creating a group of new women voters.”

—Estelle Freedman

The Edgar E. Robinson Professor in U.S. History

Before and after 1920, women who supported suffrage also sought better working conditions and women’s access to the professions. They created an international peace movement. Black women campaigned against lynching and some white women, even in the South, supported them. I have written about anti-rape efforts in the suffrage era, long before an organized anti-violence movement emerged. Once enfranchised, women aspired to jury service, office holding and military service. In 1923 the National Woman’s Party introduced the Equal Rights Amendment and lobbied Congress for decades. In so many ways, suffrage alone did not achieve the larger agenda of the women’s movement.

That said, the vote did make a difference. Suffrage had the potential to enable political change by creating a group of new women voters. Understand, though, that it took a full generation between the ratification of the suffrage amendment and the first time when women began to vote in the same proportion as men. It would take another full generation before a women’s political agenda and a gender gap in voting emerged.

While it is important to create these historical benchmarks and to celebrate these anniversaries, we always have to think about what we have gained, at what costs, for whom, and what unfinished agenda remains. What strengths of the movement can we adopt? What flaws do we want to avoid?

What can be learned from this history?

I think that one of the things we’ve learned over the decades is the importance of alliance, of being wary of single-issue causes. We need to keep our vision broad. What do the rights we seek at any given moment mean for people who are different from us? How can we support the rights that others seek and find the overlapping links between them? In our own time, we witness women of color taking the lead in identifying the intersections of race and gender, whether in Black Lives Matter, reproductive justice or environmental movements. Gender runs through all of these, race runs through all of them, our humanity runs through all of them, and we can never separate entirely any one cause from another. Feminism has to expand to question all social hierarchies to truly achieve what it professes.

Media Contacts

Ker Than, Stanford News Service: (650) 723-9820; kerthan@stanford.edu