When news breaks, New York Times correspondent Nick Casey, a Stanford alumnus, is used to getting as close to the action as possible, taking whatever risks are worth it. At least that was the pre-pandemic norm for Casey.

But COVID-19 has forced Casey and other Stanford alumni journalists to retool and refocus as they cover one of the century’s biggest stories. The pandemic has changed their subject matter and the mechanics of how they do their jobs.

While they’ve found new ways to get close to the action, their new journalism is less shoe-leather and more heavily reliant on email, smartphones and Zoom. Backyards and walk-in closets have become broadcast studios. Remote meetings have replaced the intense give-and-take among newsroom reporters on deadline. They’ve developed a patchwork system of planes, trains and automobiles to get the news out as the virus travels the world.

All the while, their playbooks and perspectives have evolved as short dispatches about a mysterious viral outbreak in China turned into intense coverage of heroic health care workers, beleaguered illness victims and societal, cultural and economic changes worldwide. Here are their stories.

Nick Casey, New York Times

“Covering the coronavirus suddenly sets up a set of concerns you’ve never faced before.”

Bob Cohn, The Economist

“The paradox of the pandemic is that just as our responsibility to deliver news and analysis is more urgent than ever, the process of getting our coverage to audiences is more difficult than ever.”

Ron Elving, National Public Radio

“There are so many things we can do from home, or from a near-home location, that we have not explored or have not put trust in until now.”

Dave Flemming, ESPN & San Francisco Giants

“Sports could be a wonderful distraction for many people right now – even if we cannot hold events with large crowds.”

Vanessa Hua, San Francisco Chronicle

“It’s been fascinating to go where people have gathered online, seeing how they find inspiration and purpose and writing their stories.”

Hannah Knowles, Washington Post

“The coronavirus has become an all-consuming, all-hands-on-deck story that seems to touch every beat imaginable.”

Ivan Maisel, ESPN

“I am a sportswriter, but with no sports to write. That made me a no-sportswriter.”

Doyle McManus, Los Angeles Times

“This won’t be the last pandemic we face. We need to learn lessons from this one to be better prepared the next time.”

Nicole Perlroth, New York Times

“Life on the cyber beat has become a game of whack-a-mole. It has been for some time, but this is unlike anything I have ever seen.”

Elisabeth Rosenthal, Kaiser Health News

“The kind of idea generation that happens hanging around in the newsroom is harder. I think most of us miss the shared sense of passion in the office.”

Gerry Shih, Washington Post

“When I filed short dispatches in January about a mysterious viral outbreak in central China, I didn’t foresee that it would eventually sweep over the world.”

Nick Casey

This has probably been the first time in the history of the New York Times where most of its journalists faced a blanket travel ban. Our headquarters are a ghost town, and reporters have been asked to do as much reporting as possible from the phone, at home. When news breaks, I am used to getting as close as I can to the action, and taking personal risks when the story is worth it – I lived in Gaza for a month at the height of the 2014 war, spent a week with leftist Colombian rebels.

But this is the first time where my presence is a big risk for my sources. An interview can get someone ill with neither party knowing it. Covering the coronavirus suddenly sets up a set of concerns you’ve never faced before.

I came off the Times’ international desk last fall to cover what was supposed to be the most important story of the year – the 2020 election. Suddenly the world was turned upside down. Entire lines of reporting that had seemed urgent just weeks ago are now rendered irrelevant. What’s the importance of the political horse race in a pandemic where the best-case model leaves as many Americans dead as the Vietnam and Korean Wars did combined? Yet politics is also more important than ever. All of the political currents of the Trump Era – populism, nationalism and the disregard for truth – have suddenly come to roost at a time of a deadly national crisis that now hinges on disputes between governors on whether it’s safe to reopen and untested cures promoted by the White House. We’re still sorting out our angles and adjustments to this new reality.

Few times have I seen everything so quickly changed and distorted by one event. Early in April, I published a story about how a college class reconvened on a videoconferencing app after Haverford College in Pennsylvania was shut down and its students evicted. On their tiny screens, they could suddenly see that not everyone was experiencing the virus the same way – one student was sitting at a vacation house in Maine, another was struggling to help her parents’ Puerto Rican food truck stay open. College was meant to be the “great equalizer” – you ate at the same cafeteria, slept on the same dorm beds. But the virus suddenly shined a light on inequality that was lurking underneath the surface of undergraduate life all the time.

In Farmington, New Mexico, few know anyone who got sick but everyone knows someone who has lost a job, and the mayor is dealing with competing views that “shouldn’t be competing.”

The virus is also overturning the lives of those I’ve written about at amazing speed. Not long before the outbreak hit the U.S., I’d come back from Gainesville, Floria, to profile Julius Irving. Julius had a powerful story. He was a former felon, who had just gotten back the right to vote and was canvassing to register other former felons to vote, too. But a fight he’d gotten into last year meant he was going back to court the next month on an attempted murder charge: He was set to possibly lose his freedom all over again, but spending the last days before trial trying to get more people to vote in the system that might put him away. Then the virus hit. Florida shut down, he lost his job canvassing for voters and was living in a car. But his court date is postponed indefinitely. Julius feels a strange combination of despair and relief.

These are the kinds of stories that are happening to people now.

Nick Casey, ’05, is a national politics correspondent for the New York Times.

Nick Casey

This has probably been the first time in the history of the New York Times where most of its journalists faced a blanket travel ban. Our headquarters are a ghost town, and reporters have been asked to do as much reporting as possible from the phone, at home. When news breaks, I am used to getting as close as I can to the action, and taking personal risks when the story is worth it – I lived in Gaza for a month at the height of the 2014 war, spent a week with leftist Colombian rebels.

But this is the first time where my presence is a big risk for my sources. An interview can get someone ill with neither party knowing it. Covering the coronavirus suddenly sets up a set of concerns you’ve never faced before.

I came off the Times’ international desk last fall to cover what was supposed to be the most important story of the year – the 2020 election. Suddenly the world was turned upside down. Entire lines of reporting that had seemed urgent just weeks ago are now rendered irrelevant. What’s the importance of the political horse race in a pandemic where the best-case model leaves as many Americans dead as the Vietnam and Korean Wars did combined? Yet politics is also more important than ever. All of the political currents of the Trump Era – populism, nationalism and the disregard for truth – have suddenly come to roost at a time of a deadly national crisis that now hinges on disputes between governors on whether it’s safe to reopen and untested cures promoted by the White House. We’re still sorting out our angles and adjustments to this new reality.

Few times have I seen everything so quickly changed and distorted by one event. Early in April, I published a story about how a college class reconvened on a videoconferencing app after Haverford College in Pennsylvania was shut down and its students evicted. On their tiny screens, they could suddenly see that not everyone was experiencing the virus the same way – one student was sitting at a vacation house in Maine, another was struggling to help her parents’ Puerto Rican food truck stay open. College was meant to be the “great equalizer” – you ate at the same cafeteria, slept on the same dorm beds. But the virus suddenly shined a light on inequality that was lurking underneath the surface of undergraduate life all the time.

In Farmington, New Mexico, few know anyone who got sick but everyone knows someone who has lost a job, and the mayor is dealing with competing views that “shouldn’t be competing.”

The virus is also overturning the lives of those I’ve written about at amazing speed. Not long before the outbreak hit the U.S., I’d come back from Gainesville, Floria, to profile Julius Irving. Julius had a powerful story. He was a former felon, who had just gotten back the right to vote and was canvassing to register other former felons to vote, too. But a fight he’d gotten into last year meant he was going back to court the next month on an attempted murder charge: He was set to possibly lose his freedom all over again, but spending the last days before trial trying to get more people to vote in the system that might put him away. Then the virus hit. Florida shut down, he lost his job canvassing for voters and was living in a car. But his court date is postponed indefinitely. Julius feels a strange combination of despair and relief.

These are the kinds of stories that are happening to people now.

Nick Casey, ’05, is a national politics correspondent for the New York Times.

Bob Cohn

For those of us in media, the paradox of the pandemic is that just as our responsibility to deliver news and analysis is more urgent than ever, the process of getting our coverage to audiences is more difficult than ever. Working from home and practicing social distance is surprisingly disruptive to newsrooms that rely on collaboration and high-paced interactions on deadline. At The Economist, where we have been in the business of group journalism since 1843, we are suddenly creating the weekly magazine – not to mention our podcasts, videos and newsletters – completely remotely. Technology tools are critical, as is the flexibility and resourcefulness of our teams. I know of audio journalists who have found high-quality sound by taping from a bedroom closet with a blanket draped over their heads.

Likewise, there have been big challenges to putting the magazine in the hands of subscribers. We publish in nine printing plants around the world and deliver issues to more than 190 countries and territories. At a time of lockdowns and supply chain disruptions, this became an operational nightmare. In recent weeks, we’ve been able to get the print magazine to 97 percent of subscribers, but not without a patchwork system of planes, trains and automobiles that changes each week as the virus moves about the planet. When a truck arrived at the German border to pick up magazines bound for Italy, authorities held them at a checkpoint for hours until finally agreeing the driver could go to the plant, pick up issues and leave the country – so long as he never left his cab.

As for myself, I live in Maryland, work out of our New York office three days a week and spend a week each month at our London headquarters. Well, that is the pre-pandemic routine. For the last month, it’s been all video meetings from my home in suburban D.C. I miss seeing my colleagues in person, but I can’t say that our productivity has suffered. So I suspect that when all this is over, we’ll all be using video a lot more, and perhaps traveling a bit less.

Bob Cohn, ’85, is president of The Economist.

Bob Cohn

For those of us in media, the paradox of the pandemic is that just as our responsibility to deliver news and analysis is more urgent than ever, the process of getting our coverage to audiences is more difficult than ever. Working from home and practicing social distance is surprisingly disruptive to newsrooms that rely on collaboration and high-paced interactions on deadline. At The Economist, where we have been in the business of group journalism since 1843, we are suddenly creating the weekly magazine – not to mention our podcasts, videos and newsletters – completely remotely. Technology tools are critical, as is the flexibility and resourcefulness of our teams. I know of audio journalists who have found high-quality sound by taping from a bedroom closet with a blanket draped over their heads.

Likewise, there have been big challenges to putting the magazine in the hands of subscribers. We publish in nine printing plants around the world and deliver issues to more than 190 countries and territories. At a time of lockdowns and supply chain disruptions, this became an operational nightmare. In recent weeks, we’ve been able to get the print magazine to 97 percent of subscribers, but not without a patchwork system of planes, trains and automobiles that changes each week as the virus moves about the planet. When a truck arrived at the German border to pick up magazines bound for Italy, authorities held them at a checkpoint for hours until finally agreeing the driver could go to the plant, pick up issues and leave the country – so long as he never left his cab.

As for myself, I live in Maryland, work out of our New York office three days a week and spend a week each month at our London headquarters. Well, that is the pre-pandemic routine. For the last month, it’s been all video meetings from my home in suburban D.C. I miss seeing my colleagues in person, but I can’t say that our productivity has suffered. So I suspect that when all this is over, we’ll all be using video a lot more, and perhaps traveling a bit less.

Bob Cohn, ’85, is president of The Economist.

Ron Elving

The pandemic has become my “subject area” because everything government does now – including the executive and legislative branches and the state governments – is more or less about COVID-19.

The pandemic shut down my office buildings. That’s both NPR and American University, where I teach in the School of Public Affairs. I began working from home on March 11.

Fortunately for me, I have a home studio for radio and online work. (Fortunately, it doubles as a medium-generous walk-in closet full of my wife’s clothes and mine. Wool and cotton clothes on hangers actually make a marvelous soft battening system for sound.) As for school, I have been teaching my two courses (Elections and Congress) using Blackboard and a variety of other online tools. I will be doing the same this summer and – one suspects – in the early fall. We shall see what comes after that.

We are adjusting amazingly well. So long as the tech holds up, and it has been miraculous that the web has held up as it has, we should be okay. There are glitches, we’ve had some Zoombombing episodes and sometimes it’s less than ideal. But the headline is that we are making it work, in journalism and academia, at least so far. It sounds like an ad for public radio, but the member stations are working together in remarkable ways that we hope will become permanent regional and national relationships. They are sharing assets and burdens like at no time I’ve witnessed.

Outside, an undeniable and palpable improvement has overtaken our immediate urban environment. It is far quieter and the air is indescribably clearer. It is like being on a beach on a sunlit morning. I am seeing details on all the signal towers in town that I did not know existed. I am seeing a fine focus on tree blossoms half a block away. We knew, always, that our air quality was bad. But now we know just how bad, and how much better it could be.

I think we should all learn to drive less – both to get to our jobs and to do our jobs. And that would include flying and other forms of transit. Apologies to the transportation industry, but a lot of the frenetic effort to be there and be face to face is not worth it. The damage to the environment is immense. The waste of time is immense.

There are so many things we can do from home, or from a near-home location, that we have not explored or have not put trust in until now.

Ron Elving, ’71, is the senior editor and correspondent on the Washington Desk for NPR News and executive in residence at American University’s School of Public Affairs.

Ron Elving

The pandemic has become my “subject area” because everything government does now – including the executive and legislative branches and the state governments – is more or less about COVID-19.

The pandemic shut down my office buildings. That’s both NPR and American University, where I teach in the School of Public Affairs. I began working from home on March 11.

Fortunately for me, I have a home studio for radio and online work. (Fortunately, it doubles as a medium-generous walk-in closet full of my wife’s clothes and mine. Wool and cotton clothes on hangers actually make a marvelous soft battening system for sound.) As for school, I have been teaching my two courses (Elections and Congress) using Blackboard and a variety of other online tools. I will be doing the same this summer and – one suspects – in the early fall. We shall see what comes after that.

We are adjusting amazingly well. So long as the tech holds up, and it has been miraculous that the web has held up as it has, we should be okay. There are glitches, we’ve had some Zoombombing episodes and sometimes it’s less than ideal. But the headline is that we are making it work, in journalism and academia, at least so far. It sounds like an ad for public radio, but the member stations are working together in remarkable ways that we hope will become permanent regional and national relationships. They are sharing assets and burdens like at no time I’ve witnessed.

Outside, an undeniable and palpable improvement has overtaken our immediate urban environment. It is far quieter and the air is indescribably clearer. It is like being on a beach on a sunlit morning. I am seeing details on all the signal towers in town that I did not know existed. I am seeing a fine focus on tree blossoms half a block away. We knew, always, that our air quality was bad. But now we know just how bad, and how much better it could be.

I think we should all learn to drive less – both to get to our jobs and to do our jobs. And that would include flying and other forms of transit. Apologies to the transportation industry, but a lot of the frenetic effort to be there and be face to face is not worth it. The damage to the environment is immense. The waste of time is immense.

There are so many things we can do from home, or from a near-home location, that we have not explored or have not put trust in until now.

Ron Elving, ’71, is the senior editor and correspondent on the Washington Desk for NPR News and executive in residence at American University’s School of Public Affairs.

Dave Flemming

Well, my world has been completely shut down with the suspension of all sporting events. This is typically my busiest time of the year – finishing college basketball season, starting MLB with Opening Day and broadcasting the Masters for ESPN in Augusta, Georgia. Instead, I have not worked an event in more than two months. I never thought I’d miss going to the airport!

Sports could be a wonderful distraction for many people right now – even if we cannot hold events with large crowds. I am still hoping that testing becomes plentiful and easy, and the emergency situations in this country calm down so that I and many others can broadcast sporting events for everyone to enjoy.

Leagues and their athletes are working hard right now to plan for the possibility of resuming games without crowds. I could see teams and leagues being much more controlling of who is allowed close access to athletes. That probably wouldn’t be a positive for fans or media members if that means fewer autographs or high-fives, and fewer chances to meet players in person, or opportunities to talk with them in informal settings. But even though there are many hurdles to clear and problems to solve, I’m sure hopeful sometime soon we can get some games back going.

For now, I’ve gone into full Dad mode – my wife is working from home a lot, so I have tried to be the homeschool teacher/lunch maker/house cleaner for our three children and us. It’s a role that suits me pretty well! If I ever leave sports broadcasting, I think I can be a short-order cook.

A few weeks ago, my fellow Giants broadcasters and I recorded a PSA over Zoom to encourage Californians to keep adhering to the social distancing guidelines. We were connected to the governor’s office in Sacramento, and midway through our session Governor Newsom must have walked by in the hall and heard us. He popped into the studio and sat down and chatted with us for several minutes – we got our own, personal COVID-19 California briefing! It was a fun conversation with a person who I think has been an excellent leader during this crisis.

Something very special I’ve seen is my wife as a volunteer and the staff at the Richmond Neighborhood Center here in San Francisco continuing weekly food pantry deliveries to seniors in need across the neighborhood. It isn’t an easy job these days, but there are so many people who need help, and help is hard to come by right now.

Dave Flemming, ’98, is entering (he hopes) his 18th season broadcasting baseball for the San Francisco Giants on radio and television. He also calls football, basketball, baseball and golf for ESPN.

Dave Flemming

Well, my world has been completely shut down with the suspension of all sporting events. This is typically my busiest time of the year – finishing college basketball season, starting MLB with Opening Day and broadcasting the Masters for ESPN in Augusta, Georgia. Instead, I have not worked an event in more than two months. I never thought I’d miss going to the airport!

Sports could be a wonderful distraction for many people right now – even if we cannot hold events with large crowds. I am still hoping that testing becomes plentiful and easy, and the emergency situations in this country calm down so that I and many others can broadcast sporting events for everyone to enjoy.

Leagues and their athletes are working hard right now to plan for the possibility of resuming games without crowds. I could see teams and leagues being much more controlling of who is allowed close access to athletes. That probably wouldn’t be a positive for fans or media members if that means fewer autographs or high-fives, and fewer chances to meet players in person, or opportunities to talk with them in informal settings. But even though there are many hurdles to clear and problems to solve, I’m sure hopeful sometime soon we can get some games back going.

For now, I’ve gone into full Dad mode – my wife is working from home a lot, so I have tried to be the homeschool teacher/lunch maker/house cleaner for our three children and us. It’s a role that suits me pretty well! If I ever leave sports broadcasting, I think I can be a short-order cook.

A few weeks ago, my fellow Giants broadcasters and I recorded a PSA over Zoom to encourage Californians to keep adhering to the social distancing guidelines. We were connected to the governor’s office in Sacramento, and midway through our session Governor Newsom must have walked by in the hall and heard us. He popped into the studio and sat down and chatted with us for several minutes – we got our own, personal COVID-19 California briefing! It was a fun conversation with a person who I think has been an excellent leader during this crisis.

Something very special I’ve seen is my wife as a volunteer and the staff at the Richmond Neighborhood Center here in San Francisco continuing weekly food pantry deliveries to seniors in need across the neighborhood. It isn’t an easy job these days, but there are so many people who need help, and help is hard to come by right now.

Dave Flemming, ’98, is entering (he hopes) his 18th season broadcasting baseball for the San Francisco Giants on radio and television. He also calls football, basketball, baseball and golf for ESPN.

Vanessa Hua

In my weekly column, I often write about social justice issues, parenthood and the creative writing community in the Bay Area. I’m the author of A River of Stars and Deceit and Other Possibilities, which was reissued in March, just as the shelter-in-place orders began and schools closed.

I knew at once the impact the pandemic had on working parents and on local authors, and I wrote columns on those angles. I also got readers involved. I put out a call for submissions for National Poetry Month and received deeply moving poems from readers, including a Stanford biology major’s musings on how the virus has shaped human history and another from a 94-year-old reflecting on everything she’d survived. I also did a column about immigrant Chinese volunteers.

At a time when xenophobia and hate crimes against Asian Americans have been on the rise, these volunteers organized quickly and effectively over WeChat, the popular Chinese social media platform. Reaching out through her network of middle school alumni, one woman figured out how to buy face masks from an audio factory that had converted its production lines.

It’s been fascinating to go where people have gathered online, seeing how they find inspiration and purpose, and writing their stories.

Vanessa Hua, ’97, is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist.

Vanessa Hua

In my weekly column, I often write about social justice issues, parenthood and the creative writing community in the Bay Area. I’m the author of A River of Stars and Deceit and Other Possibilities, which was reissued in March, just as the shelter-in-place orders began and schools closed.

I knew at once the impact the pandemic had on working parents and on local authors, and I wrote columns on those angles. I also got readers involved. I put out a call for submissions for National Poetry Month and received deeply moving poems from readers, including a Stanford biology major’s musings on how the virus has shaped human history and another from a 94-year-old reflecting on everything she’d survived. I also did a column about immigrant Chinese volunteers.

At a time when xenophobia and hate crimes against Asian Americans have been on the rise, these volunteers organized quickly and effectively over WeChat, the popular Chinese social media platform. Reaching out through her network of middle school alumni, one woman figured out how to buy face masks from an audio factory that had converted its production lines.

It’s been fascinating to go where people have gathered online, seeing how they find inspiration and purpose, and writing their stories.

Vanessa Hua, ’97, is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist.

Hannah Knowles

I’m a general assignment reporter, so I’m used to pivoting toward whatever the newsroom needs at the moment – and the coronavirus has become an all-consuming, all-hands-on-deck story that seems to touch every beat imaginable. A lot of my time is spent maintaining the Post’s coronavirus live updates page, which is free to all readers and constantly refreshing. That means working with people all across the Post in a Slack channel with hundreds of people in it; it’s really given me an appreciation for the 24/7 team effort going on here.

I’m also helping tell the stories of those who’ve died from COVID-19 and looking for other articles about the virus’s impact along the way.

I already did most of my reporting over the phone, so this hasn’t meant a drastic change in my reporting workflow and poses fewer challenges for me than for my colleagues on, for example, the Local team (and our reporters have found many ways to get out on the ground). But I do really miss seeing my co-workers and gathering in person to talk over the stories we’re going to tackle. Video’s definitely not the same.

Like a lot of people, I’ve been stunned at how quickly the pandemic has reshaped our lives. I saw that speed day to day working on the live updates page, as the bar for what we wrote about just kept rising and rising. At first, a large school district closing seemed worth its own post; within days, we were watching mostly for statewide closures, and soon shutdowns became the norm. Closures and layoffs at a big company that might once have been a standalone story became part of a cascade that you could only hope to keep up with in big-picture terms.

Sometimes, the day feels slow, and then you realize that it’s only slow in comparison to the night when, right as you were about to hand off to the overnight team, the NBA suspended its season, Tom Hanks got the coronavirus and President Trump announced a travel ban on Europe (while making some key errors) – all around the same time.

On a more personal note: I keep telling people that I’m made for quarantine because I’m a homebody even in normal times. When I moved from intern to full employee at the Post earlier this year, all the new hires were asked to share a “hidden talent” at onboarding, and I (only half-jokingly) said something like “sitting around at home with my thoughts doing nothing.” Pretty useful! But there’s also so much to do and endless stories you can take on.

I talked to some politically active members of Gen Z to see how they’re processing the pandemic, which has hit right as the oldest of them enter adulthood. Data suggests that Gen Z already cares deeply about inequality and wants government to do more to help people, and many of the young people I talked to saw the coronavirus as potentially bringing others around to their views: “I think it does give people some insight into what it’s like experiencing a time of crisis, and that realization that a lot of America lives in crisis mode 24/7, whether there’s a pandemic or not,” one teenager told me.

They talked a lot about empathy and the way we’ve become more attentive to the struggles of the most vulnerable in this moment: “We’re able to listen in a way that we haven’t been able to before,” another recent college grad said. “And I hope that when things go back to normal and it gets noisy again, we can remember to still listen and help people the way that we have now.”

The questions they raised, about what this means for the long-term, really interest me, and I don’t know the answer. Will this crisis have a lasting impact on our political priorities? Will it make us more attentive to the longstanding inequities – racial, socioeconomic and otherwise – that the coronavirus is layered on top of?

Hannah Knowles, ’19, is a general assignment reporter at the Washington Post.

Hannah Knowles

I’m a general assignment reporter, so I’m used to pivoting toward whatever the newsroom needs at the moment – and the coronavirus has become an all-consuming, all-hands-on-deck story that seems to touch every beat imaginable. A lot of my time is spent maintaining the Post’s coronavirus live updates page, which is free to all readers and constantly refreshing. That means working with people all across the Post in a Slack channel with hundreds of people in it; it’s really given me an appreciation for the 24/7 team effort going on here.

I’m also helping tell the stories of those who’ve died from COVID-19 and looking for other articles about the virus’s impact along the way.

I already did most of my reporting over the phone, so this hasn’t meant a drastic change in my reporting workflow and poses fewer challenges for me than for my colleagues on, for example, the Local team (and our reporters have found many ways to get out on the ground). But I do really miss seeing my co-workers and gathering in person to talk over the stories we’re going to tackle. Video’s definitely not the same.

Like a lot of people, I’ve been stunned at how quickly the pandemic has reshaped our lives. I saw that speed day to day working on the live updates page, as the bar for what we wrote about just kept rising and rising. At first, a large school district closing seemed worth its own post; within days, we were watching mostly for statewide closures, and soon shutdowns became the norm. Closures and layoffs at a big company that might once have been a standalone story became part of a cascade that you could only hope to keep up with in big-picture terms.

Sometimes, the day feels slow, and then you realize that it’s only slow in comparison to the night when, right as you were about to hand off to the overnight team, the NBA suspended its season, Tom Hanks got the coronavirus and President Trump announced a travel ban on Europe (while making some key errors) – all around the same time.

On a more personal note: I keep telling people that I’m made for quarantine because I’m a homebody even in normal times. When I moved from intern to full employee at the Post earlier this year, all the new hires were asked to share a “hidden talent” at onboarding, and I (only half-jokingly) said something like “sitting around at home with my thoughts doing nothing.” Pretty useful! But there’s also so much to do and endless stories you can take on.

I talked to some politically active members of Gen Z to see how they’re processing the pandemic, which has hit right as the oldest of them enter adulthood. Data suggests that Gen Z already cares deeply about inequality and wants government to do more to help people, and many of the young people I talked to saw the coronavirus as potentially bringing others around to their views: “I think it does give people some insight into what it’s like experiencing a time of crisis, and that realization that a lot of America lives in crisis mode 24/7, whether there’s a pandemic or not,” one teenager told me.

They talked a lot about empathy and the way we’ve become more attentive to the struggles of the most vulnerable in this moment: “We’re able to listen in a way that we haven’t been able to before,” another recent college grad said. “And I hope that when things go back to normal and it gets noisy again, we can remember to still listen and help people the way that we have now.”

The questions they raised, about what this means for the long-term, really interest me, and I don’t know the answer. Will this crisis have a lasting impact on our political priorities? Will it make us more attentive to the longstanding inequities – racial, socioeconomic and otherwise – that the coronavirus is layered on top of?

Hannah Knowles, ’19, is a general assignment reporter at the Washington Post.

Ivan Maisel

I am a sportswriter, but with no sports to write. That made me a no-sportswriter, which quickly became tedious: postponements, cancellations and the financial and emotional effects of each are what pass for topics. After that, you start typing what sports fans argue about – the best I ever saw, the 10 greatest, etc. It is thin broth compared to the feasts on which I regularly dine.

I have worked at home for 25 years, so no adjustments there. I have been surprised, as in being-run-over-by-a-train surprised, at how the pandemic has worsened the health of the already sickly journalism industry. Local journalism is on life support, and I’m not smart enough to figure out how it’s going to survive.

I think the road back to normalcy will take many years to construct. It will take a long time for us to be safe, not to mention feel safe, sitting in arenas, much less exchanging sweat and high-fives in competition. I think even after the development of the vaccine, the memory of social distancing will haunt us for years to come.

Ivan Maisel, ’81, is a senior writer at ESPN, host of the Down and Distance podcast and father of two Stanford graduates.

Ivan Maisel

I am a sportswriter, but with no sports to write. That made me a no-sportswriter, which quickly became tedious: postponements, cancellations and the financial and emotional effects of each are what pass for topics. After that, you start typing what sports fans argue about – the best I ever saw, the 10 greatest, etc. It is thin broth compared to the feasts on which I regularly dine.

I have worked at home for 25 years, so no adjustments there. I have been surprised, as in being-run-over-by-a-train surprised, at how the pandemic has worsened the health of the already sickly journalism industry. Local journalism is on life support, and I’m not smart enough to figure out how it’s going to survive.

I think the road back to normalcy will take many years to construct. It will take a long time for us to be safe, not to mention feel safe, sitting in arenas, much less exchanging sweat and high-fives in competition. I think even after the development of the vaccine, the memory of social distancing will haunt us for years to come.

Ivan Maisel, ’81, is a senior writer at ESPN, host of the Down and Distance podcast and father of two Stanford graduates.

Doyle McManus

Before mid-March, I was writing about the presidential campaign, the impeachment of President Trump, the U.S. collision with Iran and the prospects for peace in Afghanistan. That seems a very long time ago. Now I’m writing almost entirely about one subject: the pandemic.

And, of course, I’m working from home. No more lunches with senior officials. No more street-corner meetings with unnamed sources (although those were always rare, to be honest). But a lot more time on Zoom.

Until a few weeks ago, Congress stuck, somewhat oddly, to its in-person habits. Now senators and congresspeople are mostly working from home, too. But reporters can still hang out in the Capitol hallways and talk with members as they walk by; we just have to stay a polite 6 feet away. The White House is more complicated; the correspondents’ association has adopted a pool system to maintain social distancing in the normally crowded briefing room.

Almost all reporting is done by email, telephone and Zoom now.

I participated in a news conference via Zoom with Joe Biden one afternoon, and it was surprisingly normal – except for the reporter who showed up in a T-shirt from what appeared to be his laundry room. Decorum has taken a hit.

My hat is off to the frontline reporters who must get close to the action to show us what’s happening on the ground: roaming city streets, visiting hospitals, talking with the homeless and covering the pandemic in countries less fortunate than ours. (I have friends and colleagues in Iraq, Afghanistan and India.) Without them, we wouldn’t have the ground truths we need.

I’m now exploring what long-term changes the pandemic may produce in other areas of American life: more telework. A drive to bring medical manufacturing back onshore. A backlash against globalization. More spending on preparedness and health infrastructure. Broader support for universal healthcare and other safety net programs. All in an economy that has plunged into a deep recession.

This won’t be the last pandemic we face. We need to learn lessons from this one to be better prepared the next time.

Doyle McManus, ’74, is a Washington columnist for the Los Angeles Times, writing mostly about politics and foreign policy, and director of the journalism program at Georgetown University.

Doyle McManus

Before mid-March, I was writing about the presidential campaign, the impeachment of President Trump, the U.S. collision with Iran and the prospects for peace in Afghanistan. That seems a very long time ago. Now I’m writing almost entirely about one subject: the pandemic.

And, of course, I’m working from home. No more lunches with senior officials. No more street-corner meetings with unnamed sources (although those were always rare, to be honest). But a lot more time on Zoom.

Until a few weeks ago, Congress stuck, somewhat oddly, to its in-person habits. Now senators and congresspeople are mostly working from home, too. But reporters can still hang out in the Capitol hallways and talk with members as they walk by; we just have to stay a polite 6 feet away. The White House is more complicated; the correspondents’ association has adopted a pool system to maintain social distancing in the normally crowded briefing room.

Almost all reporting is done by email, telephone and Zoom now.

I participated in a news conference via Zoom with Joe Biden one afternoon, and it was surprisingly normal – except for the reporter who showed up in a T-shirt from what appeared to be his laundry room. Decorum has taken a hit.

My hat is off to the frontline reporters who must get close to the action to show us what’s happening on the ground: roaming city streets, visiting hospitals, talking with the homeless and covering the pandemic in countries less fortunate than ours. (I have friends and colleagues in Iraq, Afghanistan and India.) Without them, we wouldn’t have the ground truths we need.

I’m now exploring what long-term changes the pandemic may produce in other areas of American life: more telework. A drive to bring medical manufacturing back onshore. A backlash against globalization. More spending on preparedness and health infrastructure. Broader support for universal healthcare and other safety net programs. All in an economy that has plunged into a deep recession.

This won’t be the last pandemic we face. We need to learn lessons from this one to be better prepared the next time.

Doyle McManus, ’74, is a Washington columnist for the Los Angeles Times, writing mostly about politics and foreign policy, and director of the journalism program at Georgetown University.

Nicole Perlroth

I’ve been covering cyberattacks for nearly a decade, and with the pandemic, it has become a free-for-all. Nation-states and criminals alike are taking advantage of our sudden rush to virtualize anything and everything we can for profit, for intellectual property theft and in many cases to gain as much intelligence as possible about our pandemic response.

The World Health Organization is being targeted by two nation-states, and likely many others. Criminals are using COVID-themed emails to lure people into turning over their usernames and passwords. Countries we never thought of as major cybersecurity threats, like Vietnam, are now actively hacking local states and organizations that are leading the pandemic response.

The pandemic may be global, but our response to it has not been. And suddenly nation-states eager to assess what other countries are doing in response have found that cyberattacks are the best tool they have. As a result, life on the cyber beat has become a game of whack-a-mole. It has been for some time, but this is unlike anything I have ever seen.

Nicole Perlroth, MA ’08, covers cybersecurity for the New York Times and is the author of the forthcoming book, This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends.

Nicole Perlroth

I’ve been covering cyberattacks for nearly a decade, and with the pandemic, it has become a free-for-all. Nation-states and criminals alike are taking advantage of our sudden rush to virtualize anything and everything we can for profit, for intellectual property theft and in many cases to gain as much intelligence as possible about our pandemic response.

The World Health Organization is being targeted by two nation-states, and likely many others. Criminals are using COVID-themed emails to lure people into turning over their usernames and passwords. Countries we never thought of as major cybersecurity threats, like Vietnam, are now actively hacking local states and organizations that are leading the pandemic response.

The pandemic may be global, but our response to it has not been. And suddenly nation-states eager to assess what other countries are doing in response have found that cyberattacks are the best tool they have. As a result, life on the cyber beat has become a game of whack-a-mole. It has been for some time, but this is unlike anything I have ever seen.

Nicole Perlroth, MA ’08, covers cybersecurity for the New York Times and is the author of the forthcoming book, This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends.

Elisabeth Rosenthal

The newsroom I run, Kaiser Health News, is the largest nonprofit newsroom focusing on health and health policy. As such we are flourishing at this tragic moment. That’s in part because we have 60 journalists who – even in “normal” times – think about little else. We’ve spent years investigating, explaining and analyzing our health system, from hospitals and pharma to congressional spending and lobbying. So we immediately had the foundational knowledge, the contacts and the data expertise to cover an unexpected health catastrophe. We also have an unusual “non-business” model and do not depend on payment or ads for revenue, so we’ve been able to operate full-steam-ahead. We are foundation-funded and partner all of our stories with major news outlets, from the New York Times and Washington Post to the Daily Beast and PolitiFact to PBS, CBS and NPR. Once the stories have appeared in the primary partner, any other news organization can pull them from our website for free.

So we’ve pretty much been on overdrive – producing stories and overwhelmed with requests for partnerships. To list a few: As the result of public records requests in January, we broke the story about how some health officials were warning of a devastating pandemic in January in a series of emails called “Red Dawn Breaking Bad” (the Times built off of that story for its own investigation). We’ve released data stories with localizable databases about which counties in the U.S. have a lack of ICU beds and ventilators. We’ve looked at the rescue funds in the COVID spending packages and discovered huge inequities: New York is getting just a little over $10,000 per COVID patient, while some other states are getting over $300,000. We’re partnering with the Guardian on an ongoing series called “Lost on the Frontline,” documenting the healthcare workers who’ve died treating COVID. Our two-year-old “Bill of the Month” series with NPR has pivoted to highlight how patients are being stuck with COVID-related costs.

We’ve now been working virtually for weeks, and use Zoom twice a day to try to keep things coordinated. But it’s tough. The kind of idea generation that happens hanging around in the newsroom is harder. While many of us fantasized about working from home, I think most of us miss the shared sense of passion in the office. Also, reporters, who I’d normally insist travel to do their stories, are having to do much more by phone or Skype. That limits on-the-ground stories to where our staff reporters are based (D.C., California, St. Louis, Denver). But we’ve also pulled in some fantastic new freelance talent (sadly, local newspapers haven’t fared so well, so there are many talented journalists available). And some former reporters who’d left journalism altogether came back to be part of this important story. It’s been all-hands-on-deck, and one challenge we’re still trying to resolve is how to give people who’ve been working 24/7 a bit of a break.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, ’78, is editor-in-chief of Kaiser Health News, a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times and author of An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became Big Business and How You Can Take It Back. A graduate of Harvard Medical School, she worked as an emergency room physician before converting to full-time journalism.

Elisabeth Rosenthal

The newsroom I run, Kaiser Health News, is the largest nonprofit newsroom focusing on health and health policy. As such we are flourishing at this tragic moment. That’s in part because we have 60 journalists who – even in “normal” times – think about little else. We’ve spent years investigating, explaining and analyzing our health system, from hospitals and pharma to congressional spending and lobbying. So we immediately had the foundational knowledge, the contacts and the data expertise to cover an unexpected health catastrophe. We also have an unusual “non-business” model and do not depend on payment or ads for revenue, so we’ve been able to operate full-steam-ahead. We are foundation-funded and partner all of our stories with major news outlets, from the New York Times and Washington Post to the Daily Beast and PolitiFact to PBS, CBS and NPR. Once the stories have appeared in the primary partner, any other news organization can pull them from our website for free.

So we’ve pretty much been on overdrive – producing stories and overwhelmed with requests for partnerships. To list a few: As the result of public records requests in January, we broke the story about how some health officials were warning of a devastating pandemic in January in a series of emails called “Red Dawn Breaking Bad” (the Times built off of that story for its own investigation). We’ve released data stories with localizable databases about which counties in the U.S. have a lack of ICU beds and ventilators. We’ve looked at the rescue funds in the COVID spending packages and discovered huge inequities: New York is getting just a little over $10,000 per COVID patient, while some other states are getting over $300,000. We’re partnering with the Guardian on an ongoing series called “Lost on the Frontline,” documenting the healthcare workers who’ve died treating COVID. Our two-year-old “Bill of the Month” series with NPR has pivoted to highlight how patients are being stuck with COVID-related costs.

We’ve now been working virtually for weeks, and use Zoom twice a day to try to keep things coordinated. But it’s tough. The kind of idea generation that happens hanging around in the newsroom is harder. While many of us fantasized about working from home, I think most of us miss the shared sense of passion in the office. Also, reporters, who I’d normally insist travel to do their stories, are having to do much more by phone or Skype. That limits on-the-ground stories to where our staff reporters are based (D.C., California, St. Louis, Denver). But we’ve also pulled in some fantastic new freelance talent (sadly, local newspapers haven’t fared so well, so there are many talented journalists available). And some former reporters who’d left journalism altogether came back to be part of this important story. It’s been all-hands-on-deck, and one challenge we’re still trying to resolve is how to give people who’ve been working 24/7 a bit of a break.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, ’78, is editor-in-chief of Kaiser Health News, a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times and author of An American Sickness: How Healthcare Became Big Business and How You Can Take It Back. A graduate of Harvard Medical School, she worked as an emergency room physician before converting to full-time journalism.

Gerry Shih

Working as a reporter in China since 2014, I’ve felt a sense of tension and foreboding grow with every turn of major events.

I’ve seen the country slow economically and slide deeper into authoritarianism. I’ve covered a vast and murky re-education campaign of Muslims in the Xinjiang region, insurrection on the streets of Hong Kong and a trade war with the United States.

When I filed short dispatches in January about a mysterious viral outbreak in central China, I didn’t foresee that it would eventually sweep over the world. Nor did I anticipate that in the midst of the crisis in March, China would revoke visas for a dozen American journalists, including me, as bilateral relations deteriorated precisely at a moment when China and the United States needed to work together on urgent matters like global health and climate change.

Now in South Korea, where I’ve temporarily relocated, I worry about the rising death toll, the health of friends in Spain and Belgium who were likely infected and the economic repercussions that we haven’t fully grasped. In the moments when I think about work – about China – I try to wrap my mind around how the epidemic will reshape the global landscape, and how it might only further fray the ties between the world’s two largest powers.

That sense of dread I felt for years? I feel it more than ever, and I don’t think I’m alone.

Gerry Shih, ’09, is a China correspondent for the Washington Post.

Gerry Shih

Working as a reporter in China since 2014, I’ve felt a sense of tension and foreboding grow with every turn of major events.

I’ve seen the country slow economically and slide deeper into authoritarianism. I’ve covered a vast and murky re-education campaign of Muslims in the Xinjiang region, insurrection on the streets of Hong Kong and a trade war with the United States.

When I filed short dispatches in January about a mysterious viral outbreak in central China, I didn’t foresee that it would eventually sweep over the world. Nor did I anticipate that in the midst of the crisis in March, China would revoke visas for a dozen American journalists, including me, as bilateral relations deteriorated precisely at a moment when China and the United States needed to work together on urgent matters like global health and climate change.

Now in South Korea, where I’ve temporarily relocated, I worry about the rising death toll, the health of friends in Spain and Belgium who were likely infected and the economic repercussions that we haven’t fully grasped. In the moments when I think about work – about China – I try to wrap my mind around how the epidemic will reshape the global landscape, and how it might only further fray the ties between the world’s two largest powers.

That sense of dread I felt for years? I feel it more than ever, and I don’t think I’m alone.

Gerry Shih, ’09, is a China correspondent for the Washington Post.

Pete Williams

Monday, March 9, was the last time the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court entered their marble courtroom. Since then, the court building has been closed to the public. Oral argument in some of the cases scheduled for March and April was moved to early May and conducted by telephone conference call. The audio was also provided live for streaming or broadcast – two firsts for the court. Other than a notorious toilet flushing faux pas, the process has worked smoothly, although the calls do tend to go on longer than courtroom argument, and they make guessing where the justices will come down more difficult. We don’t yet know what the court will do with two of the biggest cases argued in May. They involve access to President Trump’s taxes and financial documents and the question of whether presidential electors are free agents when the electoral college meets or must vote for whoever won the popular vote in their states.

I’ve stopped my rounds of federal courthouses and the Justice Department and now instead cover the legal beat by phone and by tracking cases on the Internet, largely through the federal electronic court docket system.

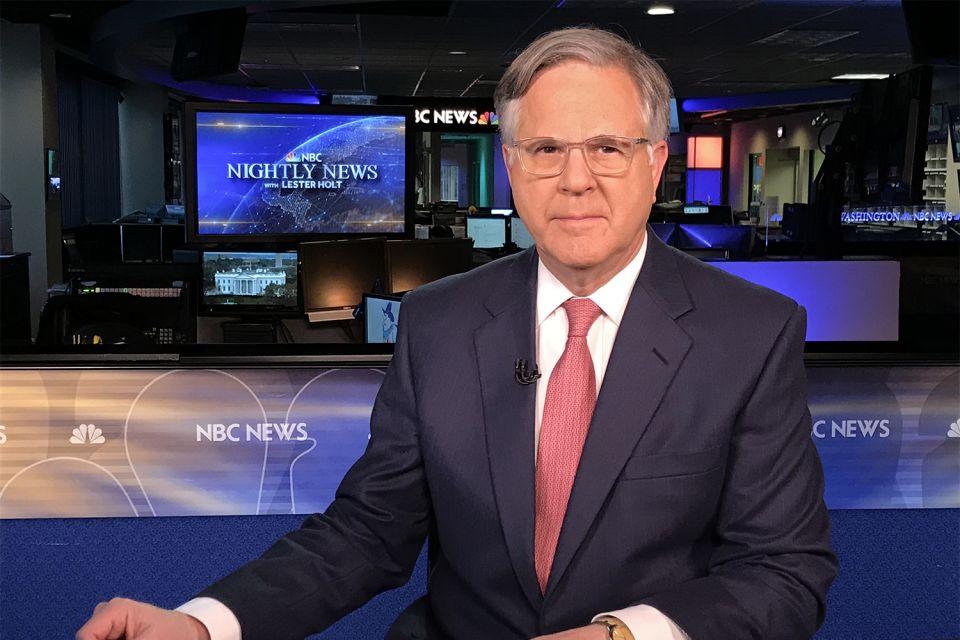

I’m also helping to fulfill a longstanding NBC News rule: Whenever the Nightly News anchor is broadcasting away from the studio, someone must be standing by in front of a studio camera in case the anchor’s remote feed fails. With Lester Holt broadcasting from his basement, I’m the standby anchor in the Washington bureau. Which means if everything goes well, you’ll never see me.

Pete Williams, ’74, covers the U.S. Supreme Court and Justice and Homeland Security departments for NBC News.

Pete Williams

Monday, March 9, was the last time the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court entered their marble courtroom. Since then, the court building has been closed to the public. Oral argument in some of the cases scheduled for March and April was moved to early May and conducted by telephone conference call. The audio was also provided live for streaming or broadcast – two firsts for the court. Other than a notorious toilet flushing faux pas, the process has worked smoothly, although the calls do tend to go on longer than courtroom argument, and they make guessing where the justices will come down more difficult. We don’t yet know what the court will do with two of the biggest cases argued in May. They involve access to President Trump’s taxes and financial documents and the question of whether presidential electors are free agents when the electoral college meets or must vote for whoever won the popular vote in their states.

I’ve stopped my rounds of federal courthouses and the Justice Department and now instead cover the legal beat by phone and by tracking cases on the Internet, largely through the federal electronic court docket system.

I’m also helping to fulfill a longstanding NBC News rule: Whenever the Nightly News anchor is broadcasting away from the studio, someone must be standing by in front of a studio camera in case the anchor’s remote feed fails. With Lester Holt broadcasting from his basement, I’m the standby anchor in the Washington bureau. Which means if everything goes well, you’ll never see me.

Pete Williams, ’74, covers the U.S. Supreme Court and Justice and Homeland Security departments for NBC News.