When Jenny Vo-Phamhi was researching a paper for Professor Richard Saller’s seminar about the Roman Empire during her very first quarter at Stanford, she was stunned to discover a problem that has changed little over 2,000 years: human trafficking.

“I was so disturbed by how little human trafficking has changed,” recalled Vo-Phamhi. She found herself eager to know more. Why does the problem continue to persist? Who is most at risk? What do the mechanisms of trafficking look like? And how can studying trafficking in Ancient Rome help us understand the problem today?

Vo-Phamhi, who is graduating from Stanford this weekend with a double major in classics and computer science, pursued a broad range of interests as an undergraduate. She’s interned at the Chan-Zuckerburg Biohub, where she helped build an mRNA imaging toolkit using machine learning, and for NASA, where she worked on instrumentation for the Arc Jet Complex. She’s also worked with Justin Leidwanger, an assistant professor of classics, where she developed computational tools to analyze artifacts used in ancient trade networks.

But the questions she had about human trafficking in Ancient Rome stayed on her mind. They eventually became the focus of her senior honors thesis and her Hume Humanities Honors Fellowship at the Stanford Humanities Center.

“I kept finding myself drawn back to the topic of human trafficking, ancient and modern, from different angles,” said Vo-Phamhi.

Searching for historical clues

While slavery was legal in ancient Rome, people were still trafficked illegally, said Vo-Phamhi.

When she set out to learn more about it, she encountered an issue: there is very little information about it.

“Rome couldn’t have functioned without slaves, yet they’re almost like ghosts in the evidence,” said Vo-Phamhi, “You hardly ever see them substantially mentioned outside law books or as a caricature in Ancient Roman comedies, which don’t always do a great job representing their lived experiences.”

In addition to looking at the few available sources in law and literature, Vo-Phamhi had to piece together their stories herself. She turned to archaeology, census data and even pored through the marble archives of the Epigraphical Museum of Athens in an independent research trip funded by a grant from the Department of Classics.

On that same research trip, Vo-Phamhi visited an archaeological site on the island of Delos, an ancient epicenter of human trafficking where some 10,000 slaves were said to pass through each day. Vo-Phamhi learned how Roman slaves came from all over the world, and with so many slaves passing through daily, it would have been impossible to distinguish who was legal and wasn’t.

As Vo-Phamhi described in her thesis, “In the Roman world, where most types of trafficking were legal and law enforcement was passive, the benefits of conducting trade in spaces highly frequented by customers gave rise to centralized marketplaces where legitimate and illegitimate traffickers could openly gather.”

Combining classics and computer science

While trafficking in Ancient Rome happened openly, in the U.S. today, where trafficking is illegal, its underground operations make it incredibly challenging to study.

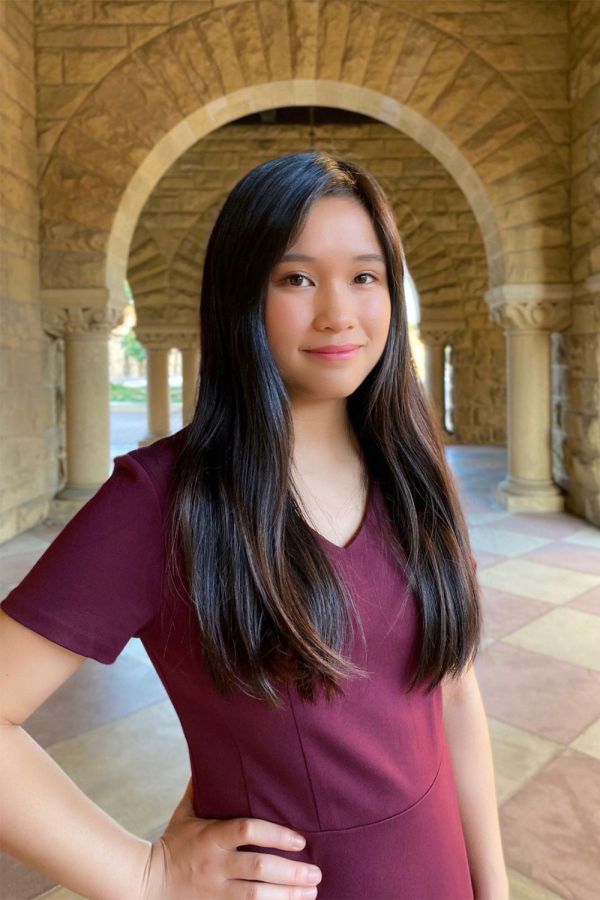

Vo-Phamhi took this photo during a research trip to the archaeological site on the Greek island Delos, an epicenter of ancient human trafficking. In the background is the ancient harbor where as many as 10,000 slaves were unloaded and sold in a single day. With so much activity, illegal traffickers could easily blend in. “This photo has been anchoring my thesis,” said Vo-Phamhi. “Also, it basically sums up my classics research experience these past four years: precious, dusty ruins (here, marble) amidst dry grass against a backdrop of blue sea and sky.” (Image credit: Jenny Vo-Phamhi)

To assemble a fuller picture of what trafficking looks like in the U.S. today, Vo-Phamhi had to turn to diverse sources for information – including the internet – where much of the modern slave trade operates.

This was where Vo-Phamhi was able to tap into her experiences as a computer science major.

For the past several months, Vo-Phamhi has worked with colleagues in the computer science department to develop machine learning tools that could help better understand large scale trends in human trafficking. She hopes that this work will ultimately lead to clues about how the trade network operates that can provide the information needed to help catch perpetrators.

Vo-Phamhi also analyzed publicly-available datasets from the U.S. government and gathered as many news articles about charges and convictions of traffickers as she could to pull together a profile of who was at risk.

Vo-Phamhi learned that, much like human trafficking victims in Ancient Rome, targets today are people from areas of armed conflict, people who are economically disadvantaged and people who are desperate to improve circumstances for themselves or their families.

“A better understanding of who’s affected and how is essential for helping people get out of these dangerous situations,” Vo-Phamhi said.

Helping identify trafficking victims

Vo-Phamhi wants to do more than just research the problem – she wants to help solve it.

When Vo-Phamhi learned that up to 80% of trafficking victims in the U.S. encounter a healthcare provider while still being trafficked, she saw an opportunity for intervention.

For the past year, Vo-Phamhi has worked with doctors in emergency medicine and primary care at Stanford Hospital and community clinics around the Bay Area and the U.S. to create an awareness campaign to help healthcare professionals realize when a trafficking victim may be in their care. Vo-Phamhi met with doctors, nurses, lawyers, law enforcement, and advocacy groups as she developed signage and pamphlets for healthcare workers as well as victims. Information includes what signs to look for, what questions to ask and what to do next.

“A major takeaway for me from the dark web work has been that it’s really hard to identify trafficked people,” Vo-Phamhi said. “So it’s extremely important to identify them on those rare occasions when they come into direct contact with people who can help.”

Mentorship, realizing limitless opportunities

Vo-Phamhi credits her accomplishments to the support of her thesis advisor and mentor, Richard Saller, the Kleinheinz Family Professor of European Studies in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

“Professor Saller encourages me to go wherever my research leads if there is important work that needs to be done,” Vo-Phamhi said. “He believes I should apply my education and training to society’s largest problems without worrying about boundaries between fields. During my first two years at Stanford, he was dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences, and in the course of our conversations, he became a leadership role model for me.”

After graduation, Vo-Phamhi is dedicating a year for research and community-engaged work.

She also plans to apply to graduate school.

“I will be thinking deeply about how I can best use my education to serve society,” said Vo-Phamhi. “As the pandemic has shown, the world needs thoughtful and capable leaders at all levels. Dr. Anthony Fauci often attributes his wisdom to his classics training. There’s profound value in that long view of humanity over the millennia.”