The Nyangatom are hard to find. To survive the harsh climate of the Omo River Valley in southern Ethiopia, they break camp, move their cattle and goats, and rebuild their lives somewhere new as often as every several weeks. Though reliable data on this population is practically nonexistent, there are an estimated 30,000 members of the tribe, many of whom are invisible in census-based surveys – the Nyangatom move too fast for the data collectors.

The invisibility might not matter if international organizations didn’t depend on census-based demographic and health surveys to design policy and distribute resources. Without any real data, experts within the World Bank, the World Health Organization and NGOs don’t have adequate information to make good policy decisions that affect these groups.

But Stanford medical student Hannah Wild wanted them to count. She’d spent 18 months living, working and learning the language with the Nyangatom after graduating from Harvard University. She wanted to show it was possible to reach this community and other nomads like them, so she stole minutes between the crush of first-year courses (Human Anatomy, Applied Biochemistry and the rest) to talk to experts within Stanford’s Center for Innovation in Global Health.

“Some of the most remote groups still in existence are nomadic pastoralists,” Wild said, adding that she wanted to work with them because their needs were rarely addressed. “As a first-year medical student, the other piece was trying to figure out where you can make an impact prior to having developed much of a clinical skillset.”

Wild couldn’t do it alone though. To get into the field and collect data, Wild would need a collaborator who knew how to work with satellite imagery to conduct a real-time census. She found Stace Maples, geospatial manager at the Stanford Geospatial Center, which is part of Stanford Libraries, who uses computational techniques to help Stanford researchers find what they need anywhere in the world.

Wild and Maples ultimately succeeded in pinpointing the location of occupied encampments across an enormous geographic area – in part through their shared knowledge of farm life and of goat’s voracious eating habits. This shared knowledge proved critical for Wild to capture census and health data that, they hope, will improve health policy and health outcomes for remote nomadic groups in Africa and elsewhere.

The Nyangatom migrate as often as every several weeks and have therefore not been included in health surveys. (Image credit: Luke Glowacki)

Songs about plants

Wild first learned of the Nyangatom while studying comparative literature as an undergraduate. She wanted to learn their traditional medical practices and won a fellowship to spend time with them after graduation. “When I was learning about their traditional medical practices, I asked ‘what’s this plant used for? What’s that plant used for?’” she said. “Everyone would start singing in response and it took a long time before I knew the language well enough to appreciate that they were singing about the plants that I was asking about.”

A native Vermonter, Wild always knew she’d go to medical school and applied during that year in the field. When she arrived at Stanford, she missed her life in the Omo River Valley – “In many ways, it was more familiar to me than Silicon Valley,” she said. She knew she’d return.

Nomadic pastoralists like the Nyangatom are among the poorest and most marginalized humans on earth. Wild felt they needed to be surveyed properly and she knew few people were lining up for the job. “I’m in a pretty neat position,” she said. “As a trainee I’m young, hungry and excited for field conditions that a lot of people wouldn’t want to put up with.”

Enthusiasm wasn’t necessarily enough. Wild would have to get herself to the Omo River Valley, get a four-wheel drive vehicle, hire staff to help run the survey, find enough Nyangatom to produce accurate data and hustle back to Stanford in time for classes in the fall.

Despite these obstacles, Wild bought a plane ticket, and with the clock ticking, she emailed Maples for logistical help.

To survive the harsh climate of the Omo River Valley in southern Ethiopia, the Nyangatom break camp, move their cattle and goats, and rebuild their lives somewhere new as often as every several weeks. (Image credit: Luke Glowacki)

Pictures, pixels and goats?

Maples studied archeology as an undergraduate and geographic information sciences in graduate school. “Points, lines, polygons, pixels,” he said. “That’s what I do.”

And solving time-sensitive, complicated challenges that impact people in need? That’s what he loves.

Within hours of meeting Wild, Maples set up a request on Humanitarian OpenStreetMap, a crowd-sourcing site where volunteers work to put “the world’s most vulnerable people and places on the map.” They identify structures on maps to help first responders navigate after natural disasters, locate refugees or contribute to achieving the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

Maples asked for help narrowing down the area of interest in the Omo River Valley, breaking it into smaller parcels and identifying any landmarks. Volunteers responded and gave Maples a good idea of where the Nyangatom might be, based where they had been in the past.

From there, Maples asked for fresh images of those locations from DigitalGlobe, a private company now called Maxar. He couldn’t rely on Google maps because the Earth view is made from hundreds of satellite images stacked on top another and made into a mosaic of the clearest, cleanest pixels from each image. “You don’t see a lot of snow,” Maples said. “You don’t see any of that stuff because they’ve taken the best pixels from the stack of images and made this beautiful image of the Earth.” The images were beautiful, but don’t reflect real-time appearances.

DigitalGlobe, however, was able to send photos of 5,000 square kilometers, all taken on a single day with one-meter resolution. You could see a car if there was one. But even on these fresh photos at high-resolution, active settlements look an awful lot like abandoned ones.

“I asked Hannah, what kind of animals do they keep?” Maples said. “At that point, I thought just cattle. And cows don’t eat shrubs. Hannah said they keep goats and I said, that’s it, that’s how we can tell.”

“I asked Hannah, ‘What kind of animals do they keep?’ At that point, I thought just cattle. And cows don’t eat shrubs. Hannah said they keep goats and I said, ‘That’s it, that’s how we can tell.’”

—Stace Maples

Geospatial Manager

Maples could manipulate the images to highlight the infrared spectrum, which is invisible to the human eye but lights up healthy vegetation in hot pink. Settlements that appeared dotted with pink meant no goats because, as any former farm kid can tell you, goats eat everything. They eat plants down to the roots and then some, where cows are sloppier or more discerning.

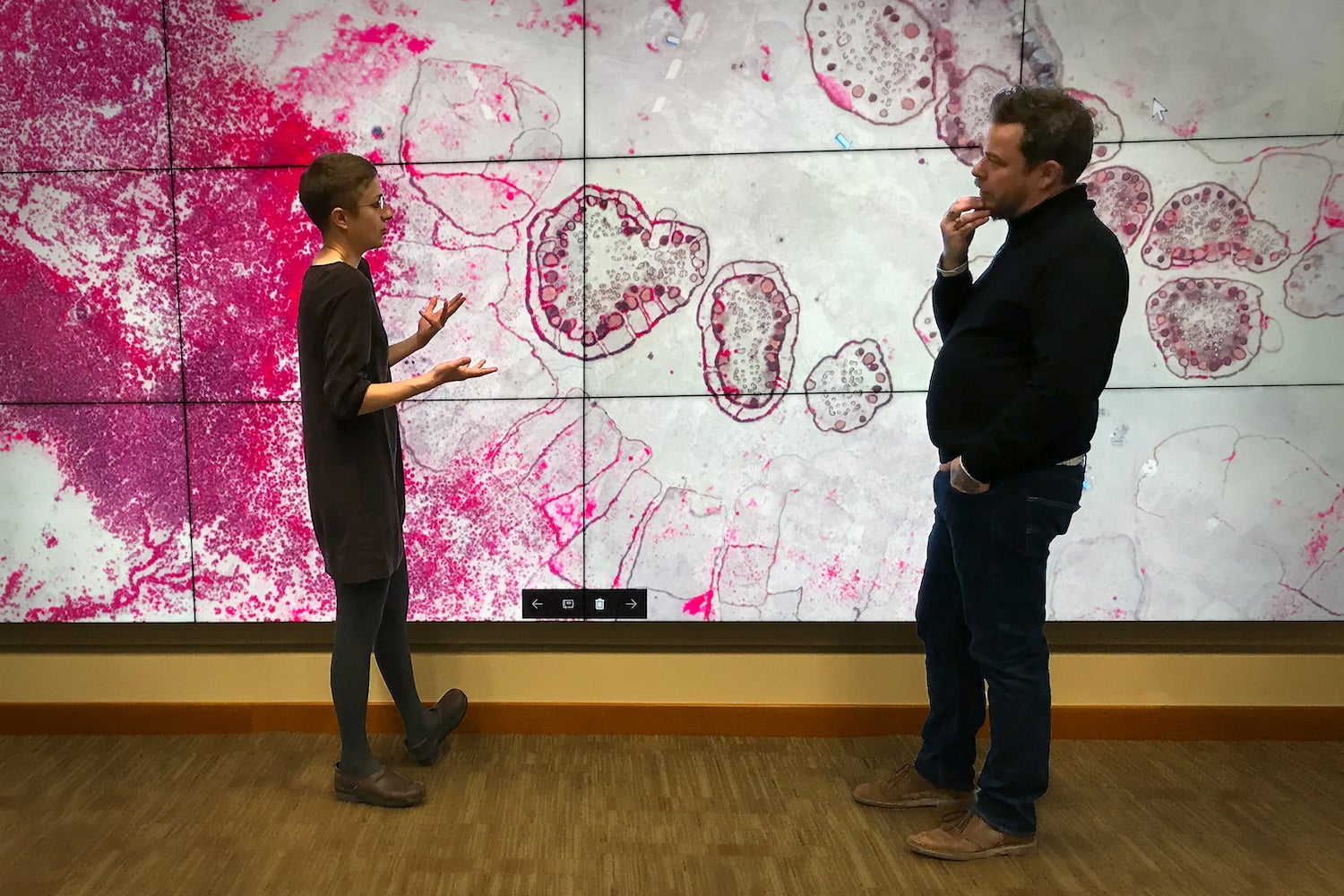

Next, Maples sequestered himself in the HANA Immersive Visualization Environment of HIVE in the Huang Engineering Center which has 35 high-definition screens arrayed together as a single screen. With the infrared-enhanced images of the Omo River Valley projected floor to ceiling in front of him, he shift-arrow keyed his way through hundreds of miles of landscape, looking for known settlements and marking the ones that had no pink and plenty of goats.

“They’re really sparsely settled so that was easy,” he said. “There were only about 250 settlements at the end.”

Maples dropped points on the images and planned a route so Wild wouldn’t have to traverse troubling terrain or march through every inch of the valley. He loaded the coordinates into a satellite phone that would guide her when she landed in Africa. And he told her to email daily so he’d know she was okay.

Hannah Wild and Stace Maples looked through satellite data for signs of settlements (the large circles). The images reveal foliage in dark pink. Absence of pink indicates the presence of goats – and a good chance that the Nyangatom are currently in residence. (Image credit: courtesy of Hannah Wild)

Under a punishing sun

In Ethiopia, Wild planned to ask mothers the same questions and take the same measurements of babies as the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). This way, she’d have all the same indicators and could compare the data. She hired locals to help and secured an old Land Rover to shuttle the team around. But keeping the crew and the car together wasn’t easy.

The car sputtered to a stop at will and the heat was so punishing by morning that the Nyangatom word for this time of day is esimokunyuk, literally, “the ground squirrel is sweating.”

Wild and her team needed to start each day around 4 every morning, when the air was already squirrel-sweating hot. Any later and it was unbearable. As it was, team members couldn’t take the pre-dawn temperatures and quit at a steady interval. Every week included at least one resignation.

In the end, Wild was able to interview 342 women, and weigh and measure 826 of their children 15 years of age and younger, 547 of whom were under age five. Back in Palo Alto, she analyzed the data and discovered that it overturned numerous commonly held assumptions about the health of pastoralist groups.

Hannah Wild surveyed 342 Nyangatom women and weighed and measured 826 of their children 15 years of age and younger as part of a health survey. (Image credit: Luke Glowacki)

When Hannah Wild conducted a health survey of the Nyangatom she found that they had overall better health than the rest of the regional population. (Image credit: Luke Glowacki)

For example, “A lot of activism has been focused on gender-relations in pastoralist societies, operating under the assumption that women aren’t allowed to seek care without their husband’s permission,” Wild said. While there is variation between different pastoralist groups, her interviews showed that yes, women asked permission but it was always granted, so their husbands weren’t the problem. The real barriers, the women said, were caused by regional conflict—the trip was too dangerous to take—and the demands of their livestock. They couldn’t leave their animals untended.

Wild’s data also upended conventional wisdom about nutrition. “The children in our sample were certainly not at a disadvantage and by some indicators, they had more favorable nutritional status then regional populations,” she said, adding that the Nyangatom children drank milk and ate animal proteins while kids in town survive on grain and food aid.

And maybe most interesting, Wild’s research disproved the commonly held belief that the Nyangatom resisted care.

When asked, “If your child was sick with diarrhea or fever, did you seek care?” the majority of women said they’d go to a clinic. If they didn’t go, the reasons weren’t cultural but logistic in a way that any mother in a lawless neighborhood would understand: the trip would be too dangerous or there’d be no one to perform their domestic labor.

It may have been convenient to believe the Nyangatom didn’t want healthcare, but the data says otherwise.

Hannah Wild and her crew drove through the blistering heat of the Omo River Valley in Ethiopia administering a health survey to women and children in Nyangatom settlements. (Image credit: Hannah Wild)

What happens next?

Desiree LaBeaud, a Stanford professor of pediatrics who studies mosquito-borne diseases, has been the principal investigator on projects in Kenya, the Caribbean and Grenada. She understands the challenges of working in remote regions, as well as the value.

“Hannah Wild highlighted a great need of all nations of the world to really pay attention to their neglected people,” LaBeaud said. “I think the powers that be say, ‘We’ll census everyone except the ones we can’t.’”

“Hannah Wild highlighted a great need of all nations of the world to really pay attention to their neglected people. I think the powers that be say, ‘We’ll census everyone except the ones we can’t.’ ”

—Desiree LaBeaud

Professor of Pediatrics

Wild’s research has already made that a tougher sell. “If one medical student can go do a DHS survey among the Nyangatom people and get it done,” LaBeaud said, “why can’t others?”

For Wild, the future holds a mix of more research and more clinical training. She’s applying to surgical residencies. “I want to pursue a career in humanitarian care in conflict, and would be devastated not to have surgical skills working in such a setting,” she said. “There’s such a need for academic rigor when you see how many policy decisions are made without adequate empiric basis that end up being detrimental, even with the best intentions to the populations that they’re trying to serve.”

Her research, published in the Journal of American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, is already changing the conversation, and the way data is collected. Save the Children International invited Wild and her co-authors to submit revisions for the organization’s survey sample methodology.

And for the Nyangatom? They will continue to move throughout the region amid squirrel-sweating heat. They will continue to be hard to find in the open space of the Omo River Valley but their data – accurate information about their health and needs – will now be visible to researchers and policymakers.

As often as every several weeks the Nyangatom in southern Ethiopia travel with their livestock to a new settlement. (Image credit: Hannah Wild)

To read all stories about Stanford science, subscribe to the biweekly Stanford Science Digest.

Produced by Amy Adams