With many students working, interning and traveling this summer, Stanford News Service asked faculty to reflect on what they did during summer breaks from college.

Their stories were as varied as their academic disciplines.

Whether it was working the night shift at a warehouse, cleaning bed sheets at a nursing home, interning for a major news network, Congress member or public defender, working at a hotel in Japan or jumping from an airplane – the summer experiences faculty had as students provided some unexpected and valuable life lessons.

They learned how feeling nervous can be helpful and sometimes necessary. They saw that failure may offer more learning potential than success. They discovered that the path to one’s career isn’t always direct, and that a “dream job” might not be the right fit, after all. They found that defying norms and expectations can lead to profound, personal transformations.

For some faculty, even ordinary jobs led to extraordinary experiences that changed how they viewed the world, inspiring questions about social justice, democracy, artificial intelligence and gender equality – topics that became the foundation of their research and academic career.

From summers in 1963 to as recent as 2007, here are some of their stories.

“I wanted to do something with my career where I could, at the end of the day, come home, look myself in the mirror and say that I took a tiny, little step to make the world a better place.”

– FORREST STUART, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF SOCIOLOGY

Karl Eikenberry

Director of the U.S.-Asia Security Initiative, Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center

“Seeing the lab for the first time, I think it was amazing to me that this was a place where people worked. That summer was filled with some disbelief that this was actually people’s jobs.”

– DUSTIN SCHROEDER, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF GEOPHYSICS

“In the summer of 1969, I thought just getting a regular job somewhere or going on vacation was not sufficient to address the pressing issues of the time.”

– GORDON CHANG, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

Audrey Shafer

Audrey Shafer delivered airplane tickets in the Boston, Massachusetts area. (Photo courtesy of Audrey Shafer)

In the summer of 1978, between graduating college and starting Stanford Medical School, I needed to make some money. But I also wanted to learn how to drive. While I had a driver’s license, I probably had no more than three hours of driving experience. Our family could not afford a car when I was in high school when most kids learn how to drive.

I took a job at a travel agency delivering airline tickets in the Boston area. Back then, particularly in business, airline tickets were booked through a travel agent who printed the physical ticket required for boarding the plane. The ticket would then need to be delivered to the office where that person worked.

The travel agency gave me a car to use, insurance and gas. Navigation was different then – it was way before GPS – so I always had a map open on the passenger seat. There were times I had no idea where to go. Boston drivers were quite quick to hit their horns at a 21-year-old learning to navigate traffic circles or rotaries – of which there were a lot of in and around the city.

There was one blunder I remember in particular. I was in a rush trying to parallel park on Massachusetts Avenue, a very busy city street by MIT. I accidentally hooked the car’s fender to the parked car in front of me. The owner of the vehicle owned a pizza shop across the street and he came out yelling at me. I thought for sure I was going to get fired – but the manager of the travel agency was so kind after I explained what happened. He told me it was OK and not to worry. His response was a huge lesson to me about being a boss: how to judge the emotional level of your employees when they’ve made an error and gauge whether they have already chastised themselves enough for their mistake.

Looking back, this was a job that simply doesn’t exist anymore. Technology has transformed the travel industry. My summer job has been replaced by customers making a few clicks to get their own airline tickets.

Having had a job that does not exist now has made me interested in how technology interfaces with and replaces humans. I think about other tasks people do that will be considered anachronistic in the future. I work in medicine where artificial intelligence is used more and more. There are many studies about the capability of AI to examine images and how technology and algorithms can be more accurate than human analysis for diagnostics. I wonder, where will such advances lead us? I am certain that a future self-driving car will handle Boston’s rotaries far better than I did!

Audrey Shafer is a professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine and director of Medicine and the Muse at Stanford Medicine.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Audrey Shafer

Audrey Shafer delivered airplane tickets in the Boston, Massachusetts area. (Photo courtesy of Audrey Shafer)

In the summer of 1978, between graduating college and starting Stanford Medical School, I needed to make some money. But I also wanted to learn how to drive. While I had a driver’s license, I probably had no more than three hours of driving experience. Our family could not afford a car when I was in high school when most kids learn how to drive.

I took a job at a travel agency delivering airline tickets in the Boston area. Back then, particularly in business, airline tickets were booked through a travel agent who printed the physical ticket required for boarding the plane. The ticket would then need to be delivered to the office where that person worked.

The travel agency gave me a car to use, insurance and gas. Navigation was different then – it was way before GPS – so I always had a map open on the passenger seat. There were times I had no idea where to go. Boston drivers were quite quick to hit their horns at a 21-year-old learning to navigate traffic circles or rotaries – of which there were a lot of in and around the city.

There was one blunder I remember in particular. I was in a rush trying to parallel park on Massachusetts Avenue, a very busy city street by MIT. I accidentally hooked the car’s fender to the parked car in front of me. The owner of the vehicle owned a pizza shop across the street and he came out yelling at me. I thought for sure I was going to get fired – but the manager of the travel agency was so kind after I explained what happened. He told me it was OK and not to worry. His response was a huge lesson to me about being a boss: how to judge the emotional level of your employees when they’ve made an error and gauge whether they have already chastised themselves enough for their mistake.

Looking back, this was a job that simply doesn’t exist anymore. Technology has transformed the travel industry. My summer job has been replaced by customers making a few clicks to get their own airline tickets.

Having had a job that does not exist now has made me interested in how technology interfaces with and replaces humans. I think about other tasks people do that will be considered anachronistic in the future. I work in medicine where artificial intelligence is used more and more. There are many studies about the capability of AI to examine images and how technology and algorithms can be more accurate than human analysis for diagnostics. I wonder, where will such advances lead us? I am certain that a future self-driving car will handle Boston’s rotaries far better than I did!

Audrey Shafer is a professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine and director of Medicine and the Muse at Stanford Medicine.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Wah Chiu

Wah Chiu was a busy boy in the cafeteria at Camp Curry in Yosemite National Park, California. (Photos courtesy of Wah Chiu)

The summer of 1966, after my freshman year at the University of California, Berkeley, I got my first job ever, working at Yosemite National Park.

I got the job through the UC Berkeley Job Placement Center; however, I had never heard of Yosemite National Park. I came to UC Berkeley as an international student from Hong Kong and I wasn’t knowledgeable about U.S. National Parks. The only thing I knew was that I had to get a job to pay my tuition. So, I interviewed for the park service, along with a few other students from UC Berkeley, who also joined me that summer.

We also didn’t know what we were going to do until we got there – which was by Greyhound Bus from Berkeley.

I remember showing up very nervous. As it was my first job, most of my attention was focused on whether I would be able to do what they were going to ask of me.

I was assigned to be a busboy in the cafeteria at Camp Curry.

Wah Chiu in the summer of 1966.

I had no idea that Yosemite was such a wonderful park. The breathtaking scenery was unimaginable.

But at first, I was focused on the work.

We had to get up at 6 in the morning. We didn’t really understand why tourists got up so early. As students, we stayed up late and woke up late – that was our life on campus. But at Yosemite, we had to start really early. We all shared outdoor tents – there were two or three of us to a tent. There was one day when all of us slept through the morning alarm and the cafeteria couldn’t open for breakfast because none of us showed up.

The cafeteria was open for breakfast, lunch and dinner, but we actually had a lot of free time in the afternoon. While others went hiking and swimming, I carried my physics textbooks through Yosemite and read them in the afternoons. Eventually, after I found my routine, I would hike or rent a bicycle on my day off.

At Yosemite, we didn’t get any tips. We did get free food, but only from the cafeteria. Our manager was a graduate student at a hotel management school, and he figured out a way to get us to work really hard: If you were the best busboy of the week, you got a New York steak, which we normally couldn’t afford on our busboy wages. That’s when I learned how to be competitive!

In those days, it was not uncommon for students at Berkeley and other campuses to get summer jobs at national parks or other non-academic jobs. A lot has changed for the current generation of undergraduate students who are focused on getting a job in their field of study where they can learn something to benefit their future career.

Although my first job did not add to my academic portfolio, it provided me a broader perspective of a regular workplace in the real world. I’m grateful for the opportunities that Yosemite afforded me not only financially but also in widening my appreciation for the natural wonders of our world. The beauty of Yosemite was one of my most memorable impressions of all that the United States has to offer.

Years later, I went back to Yosemite as a tourist, and this time I found myself waking up early to catch every moment at the park.

Wah Chiu is a professor of bioengineering, of microbiology and immunology, and of photon science at Stanford University. He is the director of Cryo-EM and the Bioimaging Division, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Wah Chiu

Wah Chiu was a busy boy in the cafeteria at Camp Curry in Yosemite National Park, California. (Photos courtesy of Wah Chiu)

The summer of 1966, after my freshman year at the University of California, Berkeley, I got my first job ever, working at Yosemite National Park.

I got the job through the UC Berkeley Job Placement Center; however, I had never heard of Yosemite National Park. I came to UC Berkeley as an international student from Hong Kong and I wasn’t knowledgeable about U.S. National Parks. The only thing I knew was that I had to get a job to pay my tuition. So, I interviewed for the park service, along with a few other students from UC Berkeley, who also joined me that summer.

We also didn’t know what we were going to do until we got there – which was by Greyhound Bus from Berkeley.

I remember showing up very nervous. As it was my first job, most of my attention was focused on whether I would be able to do what they were going to ask of me.

I was assigned to be a busboy in the cafeteria at Camp Curry.

Wah Chiu in the summer of 1966.

I had no idea that Yosemite was such a wonderful park. The breathtaking scenery was unimaginable.

But at first, I was focused on the work.

We had to get up at 6 in the morning. We didn’t really understand why tourists got up so early. As students, we stayed up late and woke up late – that was our life on campus. But at Yosemite, we had to start really early. We all shared outdoor tents – there were two or three of us to a tent. There was one day when all of us slept through the morning alarm and the cafeteria couldn’t open for breakfast because none of us showed up.

The cafeteria was open for breakfast, lunch and dinner, but we actually had a lot of free time in the afternoon. While others went hiking and swimming, I carried my physics textbooks through Yosemite and read them in the afternoons. Eventually, after I found my routine, I would hike or rent a bicycle on my day off.

At Yosemite, we didn’t get any tips. We did get free food, but only from the cafeteria. Our manager was a graduate student at a hotel management school, and he figured out a way to get us to work really hard: If you were the best busboy of the week, you got a New York steak, which we normally couldn’t afford on our busboy wages. That’s when I learned how to be competitive!

In those days, it was not uncommon for students at Berkeley and other campuses to get summer jobs at national parks or other non-academic jobs. A lot has changed for the current generation of undergraduate students who are focused on getting a job in their field of study where they can learn something to benefit their future career.

Although my first job did not add to my academic portfolio, it provided me a broader perspective of a regular workplace in the real world. I’m grateful for the opportunities that Yosemite afforded me not only financially but also in widening my appreciation for the natural wonders of our world. The beauty of Yosemite was one of my most memorable impressions of all that the United States has to offer.

Years later, I went back to Yosemite as a tourist, and this time I found myself waking up early to catch every moment at the park.

Wah Chiu is a professor of bioengineering, of microbiology and immunology, and of photon science at Stanford University. He is the director of Cryo-EM and the Bioimaging Division, Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Kathryn Olivarius

Kathryn Olivarius was a canoe guide in the Canadian wilderness. (Photos courtesy of Kathryn Olivarius)

I went to Keewaydin Canoe Camp in northern Ontario for several summers, starting at age 13. Keewaydin is not like other summer camps – we don’t do arts and crafts, archery or rock climbing. Instead, we canoe through the Canadian wilderness, paddling and portaging for weeks using traditional equipment like wood-canvas canoes; wannigans – wooden boxes in which we carry food and equipment; and tumplines – long, leather straps you tie around your gear to carry it across land. The ultimate trip as a camper is a seven-week expedition, thousands of kilometers long, through the remote wilderness of northern Quebec to the Hudson Bay. You don’t see any people outside your group or even traces of other people, except for the float plane pilot who resupplies you with food halfway through. I did this trip as a camper in 2006.

When I began college at Yale University in 2007, I joined the camp staff and worked there every summer as a guide while I was an undergraduate. I remember feeling a lot of pressure in college to get a summer internship in New York City, do academic research or spend time with my family in the UK. But I just kept going back to Keewaydin. My first summer on staff, I led the youngest campers on short trips around the base camp on Lake Temagami. In 2010, I guided 12 18-year-old girls on the Bay trip.

During her college summers, Kathryn Olivarius opted for the great outdoors.

As a staff person, you are both inside and outside the group. You want the girls to have fun and be part of that fun, but ultimately you are responsible for their safety, so have to stay somewhat removed.

But from this position of remove, you see the seismic shifts in how a group works. You feel it when morale is low, when people are hungry and tired. You can feel it too as a group gets faster, stronger and more cohesive. There is a special pride you feel when a camper reaches her own individual goal. You get to see all the little moments of growth that make the big, life-changing growth possible.

When I came to Keewaydin in 2002, the camp had only accepted girls for two years. For most of its existence – since 1893 – it had been an all-boys camp. It was obvious that many of the men – whose fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers had come of age at this camp – were not happy about girls being there. They saw carrying heavy loads across the barren tundra, axe skills and smelling like sweat and mildew for 50 days as innately masculine and hardcore.

But that didn’t matter to us. Many of the staff women had this almost subversive sense of alternative tradition-building – that we were somehow defying gender norms by teaching girls to take pride in physical strength. There was an organic, feminist energy about the experience as we worked to make the tradition open to us, too. As we paddled, the staff women talked about literature, history, pop culture and school with our campers. But we also talked about feminism, gender and equality. I’ve heard from many of my former campers that Keewaydin functioned as a kind of training ground for them to think about gender inequality and identity in their future lives.

When you spend seven weeks with a dozen other people in the wilderness, you develop deep bonds and reliance on others.

Kathryn Olivarius led girls from ages 11 to 18 through Northern Ontario.

What are the lasting lessons? Being bad at things – even failing – can be good. Failure gives you grit; challenges make you humbler and stronger. And even when you are floating down a rapid, your boat capsized and all your gear strewn across the river, you have to see the silver lining, laugh and try again. I still try to practice that mindset in real life, only now the challenges are book chapters and lecture writing, not 5K portages or a camper with a sprained ankle. Most of all, it’s important to take a deep breath, physically take yourself out your comfort zone and go off-the-grid for a bit.

Kathryn Olivarius is assistant professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

As told to Alex Shashkevich

Kathryn Olivarius

Kathryn Olivarius was a canoe guide in the Canadian wilderness. (Photos courtesy of Kathryn Olivarius)

I went to Keewaydin Canoe Camp in northern Ontario for several summers, starting at age 13. Keewaydin is not like other summer camps – we don’t do arts and crafts, archery or rock climbing. Instead, we canoe through the Canadian wilderness, paddling and portaging for weeks using traditional equipment like wood-canvas canoes; wannigans – wooden boxes in which we carry food and equipment; and tumplines – long, leather straps you tie around your gear to carry it across land. The ultimate trip as a camper is a seven-week expedition, thousands of kilometers long, through the remote wilderness of northern Quebec to the Hudson Bay. You don’t see any people outside your group or even traces of other people, except for the float plane pilot who resupplies you with food halfway through. I did this trip as a camper in 2006.

When I began college at Yale University in 2007, I joined the camp staff and worked there every summer as a guide while I was an undergraduate. I remember feeling a lot of pressure in college to get a summer internship in New York City, do academic research or spend time with my family in the UK. But I just kept going back to Keewaydin. My first summer on staff, I led the youngest campers on short trips around the base camp on Lake Temagami. In 2010, I guided 12 18-year-old girls on the Bay trip.

During her college summers, Kathryn Olivarius opted for the great outdoors.

As a staff person, you are both inside and outside the group. You want the girls to have fun and be part of that fun, but ultimately you are responsible for their safety, so have to stay somewhat removed.

But from this position of remove, you see the seismic shifts in how a group works. You feel it when morale is low, when people are hungry and tired. You can feel it too as a group gets faster, stronger and more cohesive. There is a special pride you feel when a camper reaches her own individual goal. You get to see all the little moments of growth that make the big, life-changing growth possible.

When I came to Keewaydin in 2002, the camp had only accepted girls for two years. For most of its existence – since 1893 – it had been an all-boys camp. It was obvious that many of the men – whose fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers had come of age at this camp – were not happy about girls being there. They saw carrying heavy loads across the barren tundra, axe skills and smelling like sweat and mildew for 50 days as innately masculine and hardcore.

But that didn’t matter to us. Many of the staff women had this almost subversive sense of alternative tradition-building – that we were somehow defying gender norms by teaching girls to take pride in physical strength. There was an organic, feminist energy about the experience as we worked to make the tradition open to us, too. As we paddled, the staff women talked about literature, history, pop culture and school with our campers. But we also talked about feminism, gender and equality. I’ve heard from many of my former campers that Keewaydin functioned as a kind of training ground for them to think about gender inequality and identity in their future lives.

When you spend seven weeks with a dozen other people in the wilderness, you develop deep bonds and reliance on others.

Kathryn Olivarius led girls from ages 11 to 18 through Northern Ontario.

What are the lasting lessons? Being bad at things – even failing – can be good. Failure gives you grit; challenges make you humbler and stronger. And even when you are floating down a rapid, your boat capsized and all your gear strewn across the river, you have to see the silver lining, laugh and try again. I still try to practice that mindset in real life, only now the challenges are book chapters and lecture writing, not 5K portages or a camper with a sprained ankle. Most of all, it’s important to take a deep breath, physically take yourself out your comfort zone and go off-the-grid for a bit.

Kathryn Olivarius is assistant professor of history in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

As told to Alex Shashkevich

Karl Eikenberry

Karl Eikenberry learned how to jump out of an airplane, just like this pictured US Army student paratrooper, at the Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, photo no. 6663200)

In 1971, I was a rising junior at West Point, the United States Military Academy. That summer I spent three weeks at Fort Benning, Georgia, at the U.S. Army Airborne School – also known as Jump School – for paratrooper training. The Basic Airborne Course is a physically demanding, rigorous three-week curriculum that teaches soldiers how to jump from a U.S. military aircraft in flight and safely land on the ground.

There is a popular expression about how life begins at the end of the comfort zone. Before I began the training, my comfort zone certainly did not include jumping out of airplanes. Even after three weeks of intense preparation – which included a week of jumping from 34-foot towers – I was nervous about my first jump.

It was a one-hour ride from the military airfield at Fort Benning to the drop zone and I remember sitting there inside a U.S. Air Force C-130 transport aircraft, all loaded up with my parachute, helmet and other equipment on.

As the aircraft rumbled toward the drop zone, one of the cadre, a very seasoned sergeant, gets in front of me, grabs my two shoulder straps, looks me in the face and because of the deafening engine noise, shouted at me: “Airborne,”– which is how all students are addressed – “are you nervous?”

And although I was nervous, I gave the answer I thought he wanted to hear.

“No, Sergeant,” I said. “I’m not nervous.”

The sergeant looked at me and very calmly said: “Airborne, I want you to be nervous. This is your first jump.”

I’ll never forget that expression on his face and his sincerity.

“Every time you jump out of an airplane in the future, I want you to be nervous,” the sergeant said to me. “Because when you are nervous, you are thinking hard about the challenge you are facing. In your mind, you are going through all the training you had – what is the next thing to do and what to do should something go wrong.”

And then he said: “What I don’t want you to do is be afraid. Be nervous, but don’t be afraid. If you let your fears control you, then you are going to make a mistake.”

As I waited the several seconds for my parachute to deploy and began my descent to the ground below, I remembered that sergeant’s words of wisdom – and I focused, focused, focused. You have deep appreciation for the different processes that led you to that moment and all the rules to do it safely – they teach you certain ways to exit the aircraft, check your parachute canopy for a full opening, steer clear of fellow jumpers, choose a landing point and steer into the wind and how to make contact with the ground to avoid injury.

It’s a good life lesson. Whether you are getting ready for a job interview or delivering a presentation, you should feel a little nervous. If you don’t feel nervous at all and are just feeling good, you are probably not going to be on your best game. But also – don’t be afraid.

And that’s one of the lessons I learned from the U.S. Army Airborne School.

Karl Eikenberry is the Oksenberg-Rohlen Fellow and director of the U.S.-Asia Security Initiative at the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center. He is a retired U.S. Army lieutenant general and served as the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan from April 2009 to July 2011.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Karl Eikenberry

Karl Eikenberry learned how to jump out of an airplane, just like this pictured US Army student paratrooper, at the Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, photo no. 6663200)

In 1971, I was a rising junior at West Point, the United States Military Academy. That summer I spent three weeks at Fort Benning, Georgia, at the U.S. Army Airborne School – also known as Jump School – for paratrooper training. The Basic Airborne Course is a physically demanding, rigorous three-week curriculum that teaches soldiers how to jump from a U.S. military aircraft in flight and safely land on the ground.

There is a popular expression about how life begins at the end of the comfort zone. Before I began the training, my comfort zone certainly did not include jumping out of airplanes. Even after three weeks of intense preparation – which included a week of jumping from 34-foot towers – I was nervous about my first jump.

It was a one-hour ride from the military airfield at Fort Benning to the drop zone and I remember sitting there inside a U.S. Air Force C-130 transport aircraft, all loaded up with my parachute, helmet and other equipment on.

As the aircraft rumbled toward the drop zone, one of the cadre, a very seasoned sergeant, gets in front of me, grabs my two shoulder straps, looks me in the face and because of the deafening engine noise, shouted at me: “Airborne,”– which is how all students are addressed – “are you nervous?”

And although I was nervous, I gave the answer I thought he wanted to hear.

“No, Sergeant,” I said. “I’m not nervous.”

The sergeant looked at me and very calmly said: “Airborne, I want you to be nervous. This is your first jump.”

I’ll never forget that expression on his face and his sincerity.

“Every time you jump out of an airplane in the future, I want you to be nervous,” the sergeant said to me. “Because when you are nervous, you are thinking hard about the challenge you are facing. In your mind, you are going through all the training you had – what is the next thing to do and what to do should something go wrong.”

And then he said: “What I don’t want you to do is be afraid. Be nervous, but don’t be afraid. If you let your fears control you, then you are going to make a mistake.”

As I waited the several seconds for my parachute to deploy and began my descent to the ground below, I remembered that sergeant’s words of wisdom – and I focused, focused, focused. You have deep appreciation for the different processes that led you to that moment and all the rules to do it safely – they teach you certain ways to exit the aircraft, check your parachute canopy for a full opening, steer clear of fellow jumpers, choose a landing point and steer into the wind and how to make contact with the ground to avoid injury.

It’s a good life lesson. Whether you are getting ready for a job interview or delivering a presentation, you should feel a little nervous. If you don’t feel nervous at all and are just feeling good, you are probably not going to be on your best game. But also – don’t be afraid.

And that’s one of the lessons I learned from the U.S. Army Airborne School.

Karl Eikenberry is the Oksenberg-Rohlen Fellow and director of the U.S.-Asia Security Initiative at the Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center. He is a retired U.S. Army lieutenant general and served as the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan from April 2009 to July 2011.

As told to Melissa De Witte

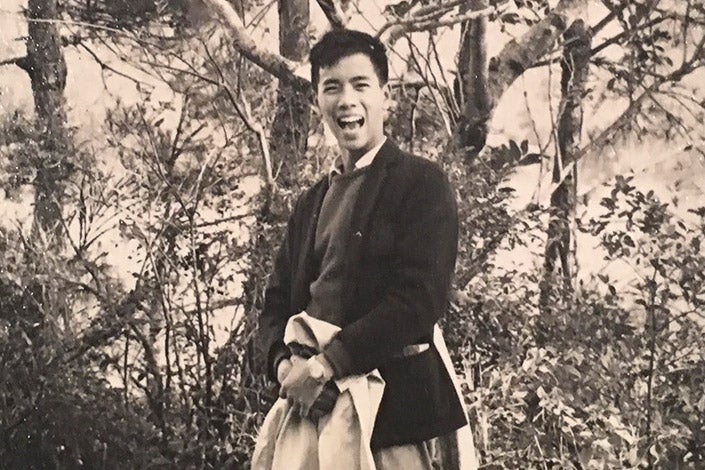

Amy Zegart

Amy Zegart interned at CBS Evening News in New York City. (Photo courtesy of Amy Zegart)

In college, I really wanted a career in broadcast journalism. There was no internet, so at the beginning of my junior year, I sent a shot-in-the-dark snail mail letter to Diane Sawyer, who was a television star at CBS News. The gist of it was, “Hi. You’re from Kentucky, and so am I. Will you hire me to be your summer intern?” It wasn’t exactly the strongest pitch, and the connection was a stretch to say the least, but it was all I had.

To her credit, Diane Sawyer wrote back and told me in the nicest possible way that no, she would not hire me, but I should write to someone else at CBS. Which I did. Every month. All year long. As time went by, I didn’t get an answer, but I did get endless grief from my friends. “There goes Amy, writing to CBS again. How’s that internship coming?”

And then, lo and behold, one day near the end of school, I got a call from CBS Evening News saying I’d landed one of the show’s two coveted internships in New York. When I asked why on Earth they hired me without an interview, they said anyone who wrote that many letters had the persistence of a good journalist. So, I moved to New York, armed with three cans of pepper spray my parents gave me.

It turned out to be an incredible experience that changed my life, but not in the way I ever expected. One disastrous night I nearly made the entire network go off the air. To be fair, it wasn’t entirely my fault. The lead story was changing, an editor was making last-minute adjustments, and my job was to hand carry the edited videotape from the editing booth to the control room upstairs where it had to be inserted into some equipment to be broadcast.

Thirty years later, I can still picture the scene as I bolted into the control room, panting and panicking, with seconds to spare before the CBS feed nationwide went black. There was screaming. It was bedlam. Smoke was everywhere because the director – who runs the broadcast – was so stressed out, he was chain-smoking cigarettes out of both hands.

In that moment I realized two things: One, I am not a fast runner; and two, I do not like tight deadlines. Soon after, the show’s executive producer encouraged me to apply for a Fulbright Fellowship and gently suggested that I consider a career with more research and less time pressure. And that’s how I started thinking about becoming an academic.

Amy Zegart is the Davies Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Amy Zegart

Amy Zegart interned at CBS Evening News in New York City. (Photo courtesy of Amy Zegart)

In college, I really wanted a career in broadcast journalism. There was no internet, so at the beginning of my junior year, I sent a shot-in-the-dark snail mail letter to Diane Sawyer, who was a television star at CBS News. The gist of it was, “Hi. You’re from Kentucky, and so am I. Will you hire me to be your summer intern?” It wasn’t exactly the strongest pitch, and the connection was a stretch to say the least, but it was all I had.

To her credit, Diane Sawyer wrote back and told me in the nicest possible way that no, she would not hire me, but I should write to someone else at CBS. Which I did. Every month. All year long. As time went by, I didn’t get an answer, but I did get endless grief from my friends. “There goes Amy, writing to CBS again. How’s that internship coming?”

And then, lo and behold, one day near the end of school, I got a call from CBS Evening News saying I’d landed one of the show’s two coveted internships in New York. When I asked why on Earth they hired me without an interview, they said anyone who wrote that many letters had the persistence of a good journalist. So, I moved to New York, armed with three cans of pepper spray my parents gave me.

It turned out to be an incredible experience that changed my life, but not in the way I ever expected. One disastrous night I nearly made the entire network go off the air. To be fair, it wasn’t entirely my fault. The lead story was changing, an editor was making last-minute adjustments, and my job was to hand carry the edited videotape from the editing booth to the control room upstairs where it had to be inserted into some equipment to be broadcast.

Thirty years later, I can still picture the scene as I bolted into the control room, panting and panicking, with seconds to spare before the CBS feed nationwide went black. There was screaming. It was bedlam. Smoke was everywhere because the director – who runs the broadcast – was so stressed out, he was chain-smoking cigarettes out of both hands.

In that moment I realized two things: One, I am not a fast runner; and two, I do not like tight deadlines. Soon after, the show’s executive producer encouraged me to apply for a Fulbright Fellowship and gently suggested that I consider a career with more research and less time pressure. And that’s how I started thinking about becoming an academic.

Amy Zegart is the Davies Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

As told to Melissa De Witte

David Kennedy

David Kennedy as pictured in the 1963 Stanford yearbook. (Photo courtesy of David Kennedy)

It was the summer of 1962, between my junior and senior year as a history major at Stanford. There was no such thing as internships back then. We all worked during summers at whatever jobs we could find.

I started that summer as a tour guide at the Seattle World’s Fair. I drove a little golf cart around and gave the same pitch over and over again, all day long. By the second week, I was bored stiff. The pay wasn’t very good either.

A helpful uncle intervened to get me a job working for a flood-control district in the Snoqualmie River watershed, in the Cascade Mountain foothills east of Seattle. We cut brush and busted beaver dams and cleared sight lines through the forest for survey crews. For all practical purposes it was like working in a logging camp. The foremen didn’t care that I had no logging experience – they just wanted physically strong young men and I just wanted not to be driving a golf cart around all day.

And so, into the woods I went. On my first day they handed me a chainsaw and a big double-headed axe. They pointed to some trees marked with colored tape and told me to cut them down. No one bothered to explain how to do it. I had never cut down anything bigger than a Christmas tree. The 80-foot-tall trees I was facing now were another matter altogether.

It’s quite a feeling when a 10-ton tree hits the ground. It’s like a mini earthquake. You bounce, the ground bounces.

We also had to clear brush that we would burn in big fire pits, feeding the fire all day long. Our shirts only lasted a day or two – the sparks from the fires burned right through the fabric. Our chests and arms were covered in little burns.

Once in a while our machetes struck a hornet’s nest and we had to jump into the river to get clear of the hornets. Once I was stung so badly around my right ear that it swelled up like a cauliflower. A co-worker was stung so badly that he had to be taken away by ambulance and didn’t return to work for the rest of summer.

It was different from Stanford all right. It exposed me to ways of life and work that were galaxies distant from what I knew or what I was preparing for. That summer gave me a deep appreciation for what hard, physical labor is, what it means to work with one’s body for a living, and to do it under dangerous conditions. It introduced me to people I would never have met on campus. It was an early lesson in how vast and varied the world is and how fortunate was my place in it.

And I also learned how to fell some mighty big trees.

David M. Kennedy is the Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History, Emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

As told to Melissa De Witte

David Kennedy

David Kennedy as pictured in the 1963 Stanford yearbook. (Photo courtesy of David Kennedy)

It was the summer of 1962, between my junior and senior year as a history major at Stanford. There was no such thing as internships back then. We all worked during summers at whatever jobs we could find.

I started that summer as a tour guide at the Seattle World’s Fair. I drove a little golf cart around and gave the same pitch over and over again, all day long. By the second week, I was bored stiff. The pay wasn’t very good either.

A helpful uncle intervened to get me a job working for a flood-control district in the Snoqualmie River watershed, in the Cascade Mountain foothills east of Seattle. We cut brush and busted beaver dams and cleared sight lines through the forest for survey crews. For all practical purposes it was like working in a logging camp. The foremen didn’t care that I had no logging experience – they just wanted physically strong young men and I just wanted not to be driving a golf cart around all day.

And so, into the woods I went. On my first day they handed me a chainsaw and a big double-headed axe. They pointed to some trees marked with colored tape and told me to cut them down. No one bothered to explain how to do it. I had never cut down anything bigger than a Christmas tree. The 80-foot-tall trees I was facing now were another matter altogether.

It’s quite a feeling when a 10-ton tree hits the ground. It’s like a mini earthquake. You bounce, the ground bounces.

We also had to clear brush that we would burn in big fire pits, feeding the fire all day long. Our shirts only lasted a day or two – the sparks from the fires burned right through the fabric. Our chests and arms were covered in little burns.

Once in a while our machetes struck a hornet’s nest and we had to jump into the river to get clear of the hornets. Once I was stung so badly around my right ear that it swelled up like a cauliflower. A co-worker was stung so badly that he had to be taken away by ambulance and didn’t return to work for the rest of summer.

It was different from Stanford all right. It exposed me to ways of life and work that were galaxies distant from what I knew or what I was preparing for. That summer gave me a deep appreciation for what hard, physical labor is, what it means to work with one’s body for a living, and to do it under dangerous conditions. It introduced me to people I would never have met on campus. It was an early lesson in how vast and varied the world is and how fortunate was my place in it.

And I also learned how to fell some mighty big trees.

David M. Kennedy is the Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History, Emeritus, in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

As told to Melissa De Witte

James Hamilton

James Hamilton interned on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. (Photos courtesy of James Hamilton)

The words that inspired my senior thesis were memorable: “That shouldn’t be here.”

It was 1980, and I was working as an intern for a House member on Capitol Hill. I had just finished my first year in college and I had hopes of using knowledge gained from my favorite class, Principles of Economics, in my summer job.

Most days started with my opening and sorting the office mail. Occasionally I drafted a response if a constituent wrote in with a policy question. One day I opened an envelope and found a campaign contribution check from a political action committee (PAC) for a hotel chain. When I brought it to a staffer, he took the check, and noted it was improper to receive contributions in a congressional office. While a Congress member’s campaign can accept political donations from PACs, this transfer should not go on in a House office. Under federal election law, if an unexpected check arrived in the mail at a congressional office just like the one I opened, it would need to be passed onto the campaign committee immediately – which the staffer ensured happened.

Prior to interning on Capitol Hill, Hamilton worked as a tour guide and messenger at the US Supreme Court.

That chain of events led me to start learning more about PACs. What motivated their giving patterns? Did they care about a candidate’s stand on social issues, or only votes on bills related to their economic interests? Those questions were the foundation of my senior honors thesis, “PAC’ing the Senate in 1980: An Econometric Study of the Contributions of Political Action Committees.” Pursuing questions about the interplay of politics and policy eventually led me to apply for a PhD in economics. I’m still working on the challenge of how to hold public officials accountable, most recently in my book Democracy’s Detectives: The Economics of Investigative Journalism.

I learned that summer you can find research ideas anywhere if you keep your eyes open and, as in Watergate, follow the money.

James T. Hamilton holds the Hearst Professorship in the School of Humanities and Sciences. He is a professor of communication, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research and the director of the Stanford Journalism Program.

Go to the web site to view the video.

James Hamilton

James Hamilton interned on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. (Photos courtesy of James Hamilton)

The words that inspired my senior thesis were memorable: “That shouldn’t be here.”

It was 1980, and I was working as an intern for a House member on Capitol Hill. I had just finished my first year in college and I had hopes of using knowledge gained from my favorite class, Principles of Economics, in my summer job.

Most days started with my opening and sorting the office mail. Occasionally I drafted a response if a constituent wrote in with a policy question. One day I opened an envelope and found a campaign contribution check from a political action committee (PAC) for a hotel chain. When I brought it to a staffer, he took the check, and noted it was improper to receive contributions in a congressional office. While a Congress member’s campaign can accept political donations from PACs, this transfer should not go on in a House office. Under federal election law, if an unexpected check arrived in the mail at a congressional office just like the one I opened, it would need to be passed onto the campaign committee immediately – which the staffer ensured happened.

Prior to interning on Capitol Hill, Hamilton worked as a tour guide and messenger at the US Supreme Court.

That chain of events led me to start learning more about PACs. What motivated their giving patterns? Did they care about a candidate’s stand on social issues, or only votes on bills related to their economic interests? Those questions were the foundation of my senior honors thesis, “PAC’ing the Senate in 1980: An Econometric Study of the Contributions of Political Action Committees.” Pursuing questions about the interplay of politics and policy eventually led me to apply for a PhD in economics. I’m still working on the challenge of how to hold public officials accountable, most recently in my book Democracy’s Detectives: The Economics of Investigative Journalism.

I learned that summer you can find research ideas anywhere if you keep your eyes open and, as in Watergate, follow the money.

James T. Hamilton holds the Hearst Professorship in the School of Humanities and Sciences. He is a professor of communication, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research and the director of the Stanford Journalism Program.

Go to the web site to view the video.

Estelle Freedman

Estelle Freedman turned 21-years-old during her college summer working at an international hotel in Japan. (Photos courtesy of Estelle Freedman)

In 1968, the summer before my senior year at Barnard College, I wanted to get far away from the political turmoil that had rocked the country, and my campus, that year. I needed to earn money and the opportunity to take an exchange job brought me to an international hotel in Nagoya, Japan. I had never heard of this city of nearly 3 million people. I spoke no Japanese. This first experience in independent living and foreign travel proved life-changing.

In June I settled into a workers’ dormitory on the edge of the city. Six days a week I took a bus downtown to perform a range of female labor. Each morning I waited tables at the breakfast service in the main dining room; then I rotated to serve at the ground-floor coffee shop. I spent part of every afternoon staffing the front information desk to assist English-speaking guests. During late afternoons, several days a week, I taught an English-language class for hotel workers – maids, waiters and busboys who wanted to improve their positions. I made up the practical conversation lessons based on my observations of interactions between guests and workers. I had once sworn that when I chose a career it would be “anything but a teacher,” because that was practically the only career available to women. In this first teaching experience, though, I had a taste of the rewards of sharing knowledge with eager and appreciative students.

The first weeks I experienced what a friend later told me was called “culture shock.” I adapted gradually to the isolation born of my ignorance of the language and of social norms. I learned what it meant to be a foreigner when schoolchildren pointed at me and called out “Gaijin!” The abundant kindness of my co-workers and local college students, many eager to improve their English, helped me adapt and flourish. They also forced me to articulate my own values when they asked: What did I think of Black power? Student power? Why is the U.S. in Southeast Asia? Why are there U.S. bases in Japan? Weekend hikes and sightseeing opened my eyes, as well. That summer I began to think in new ways about my own identity – as an American, a student, a worker and as a woman.

Estelle Freedman’s experience in Japan showed her new ways to view the U.S. and the world.

I did not consider myself a feminist when I went to Japan – the term had only recently resurfaced. But rereading my journal from that summer, I can detect some of the seeds of my further political awakening when I returned. I described the images of women “carrying babies on their backs / in work pants pushing carts through streets / tearing down a building / carrying loads as big as themselves … working in the kitchen all morning / all afternoon, caring for the men and children / bent over in the rice fields / still bent walking down the street … [and] the well-to-do in kimono and obi / refined, poised, fan in hand.” I puzzled over arranged marriages, which my closest Japanese friends swore to refuse. It now strikes me how little I recognized at the time the parallels within the U.S., how it took this long journey to see in an unfamiliar culture what turned out to be a more global pattern.

When I returned to school in the fall after turning 21 in Japan, I carried with me a lifelong gratitude to everyone there who so graciously provided gifts and insights that I still treasure.

Estelle B. Freedman is the Edgar E. Robinson Professor in U.S. History in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Excerpted and edited from Estelle B. Freedman, “Women’s/Feminist/Gender Studies in the U.S.: Personal Reflections on Forty Years of Scholarly Activism” (Nagoya, Japan: Tokai Foundation for Gender Studies, Summer 2018).

Estelle Freedman

Estelle Freedman turned 21-years-old during her college summer working at an international hotel in Japan. (Photos courtesy of Estelle Freedman)

In 1968, the summer before my senior year at Barnard College, I wanted to get far away from the political turmoil that had rocked the country, and my campus, that year. I needed to earn money and the opportunity to take an exchange job brought me to an international hotel in Nagoya, Japan. I had never heard of this city of nearly 3 million people. I spoke no Japanese. This first experience in independent living and foreign travel proved life-changing.

In June I settled into a workers’ dormitory on the edge of the city. Six days a week I took a bus downtown to perform a range of female labor. Each morning I waited tables at the breakfast service in the main dining room; then I rotated to serve at the ground-floor coffee shop. I spent part of every afternoon staffing the front information desk to assist English-speaking guests. During late afternoons, several days a week, I taught an English-language class for hotel workers – maids, waiters and busboys who wanted to improve their positions. I made up the practical conversation lessons based on my observations of interactions between guests and workers. I had once sworn that when I chose a career it would be “anything but a teacher,” because that was practically the only career available to women. In this first teaching experience, though, I had a taste of the rewards of sharing knowledge with eager and appreciative students.

The first weeks I experienced what a friend later told me was called “culture shock.” I adapted gradually to the isolation born of my ignorance of the language and of social norms. I learned what it meant to be a foreigner when schoolchildren pointed at me and called out “Gaijin!” The abundant kindness of my co-workers and local college students, many eager to improve their English, helped me adapt and flourish. They also forced me to articulate my own values when they asked: What did I think of Black power? Student power? Why is the U.S. in Southeast Asia? Why are there U.S. bases in Japan? Weekend hikes and sightseeing opened my eyes, as well. That summer I began to think in new ways about my own identity – as an American, a student, a worker and as a woman.

Estelle Freedman’s experience in Japan showed her new ways to view the U.S. and the world.

I did not consider myself a feminist when I went to Japan – the term had only recently resurfaced. But rereading my journal from that summer, I can detect some of the seeds of my further political awakening when I returned. I described the images of women “carrying babies on their backs / in work pants pushing carts through streets / tearing down a building / carrying loads as big as themselves … working in the kitchen all morning / all afternoon, caring for the men and children / bent over in the rice fields / still bent walking down the street … [and] the well-to-do in kimono and obi / refined, poised, fan in hand.” I puzzled over arranged marriages, which my closest Japanese friends swore to refuse. It now strikes me how little I recognized at the time the parallels within the U.S., how it took this long journey to see in an unfamiliar culture what turned out to be a more global pattern.

When I returned to school in the fall after turning 21 in Japan, I carried with me a lifelong gratitude to everyone there who so graciously provided gifts and insights that I still treasure.

Estelle B. Freedman is the Edgar E. Robinson Professor in U.S. History in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Excerpted and edited from Estelle B. Freedman, “Women’s/Feminist/Gender Studies in the U.S.: Personal Reflections on Forty Years of Scholarly Activism” (Nagoya, Japan: Tokai Foundation for Gender Studies, Summer 2018).

Dan Edelstein

Dan Edelstein worked at a nursing home in Geneva, Switzerland. (Image Credit: Getty Images)

In the summer of 1993, after I graduated from high school in Switzerland, a couple of my friends and I worked as nursing assistants at a nursing home in Geneva. Our job was to change the patients’ bedsheets, change their diapers and clean other things. It was a very sad environment, but the work paid well.

I already knew I wanted to study literature in college and that I wasn’t going to go into the medical field. But there was nothing like working in that nursing home to give me an insight into so many existential questions, such as “What is it like to look back at your life at that moment?” and “What is it like to be losing your mind?”

I remember one moment from that summer particularly vividly. There was a very cantankerous woman who had the reputation of being really difficult. She was bedridden by the time I got there. It was clear that she didn’t have much longer to live. She was of very tiny stature. She almost looked a child, very disconnected from reality. There was a Buddha statue next to her bed.

I was interested in Buddhism at the time. So, one day after I cleaned her room, I sat down and took her hand in mine, and chanted “Om” for a few moments. She gave me a look I’ll never forget. She couldn’t really communicate any more, but it was like a light went on in her face that I hadn’t seen ever before. It was such a moving moment – to realize what it meant for someone to do something as simple as hold their hand and make a sound that’s meaningful to them. I learned that she died about a month afterward.

Dan Edelstein is the William H. Bonsall Professor in French and chair of the Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

As told to Alex Shashkevich

Image credit: Getty Images

Dan Edelstein

Dan Edelstein worked at a nursing home in Geneva, Switzerland. (Image Credit: Getty Images)

In the summer of 1993, after I graduated from high school in Switzerland, a couple of my friends and I worked as nursing assistants at a nursing home in Geneva. Our job was to change the patients’ bedsheets, change their diapers and clean other things. It was a very sad environment, but the work paid well.

I already knew I wanted to study literature in college and that I wasn’t going to go into the medical field. But there was nothing like working in that nursing home to give me an insight into so many existential questions, such as “What is it like to look back at your life at that moment?” and “What is it like to be losing your mind?”

I remember one moment from that summer particularly vividly. There was a very cantankerous woman who had the reputation of being really difficult. She was bedridden by the time I got there. It was clear that she didn’t have much longer to live. She was of very tiny stature. She almost looked a child, very disconnected from reality. There was a Buddha statue next to her bed.

I was interested in Buddhism at the time. So, one day after I cleaned her room, I sat down and took her hand in mine, and chanted “Om” for a few moments. She gave me a look I’ll never forget. She couldn’t really communicate any more, but it was like a light went on in her face that I hadn’t seen ever before. It was such a moving moment – to realize what it meant for someone to do something as simple as hold their hand and make a sound that’s meaningful to them. I learned that she died about a month afterward.

Dan Edelstein is the William H. Bonsall Professor in French and chair of the Division of Literatures, Cultures and Languages in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

As told to Alex Shashkevich

Image credit: Getty Images

Mary Hawn

Mary Hawn worked in a scientific research lab at the University of Michigan. Her research won her an award from the American Gastroenterological Association which she received (as pictured) at their annual meeting in 1985. (Photo courtesy of Mary Hawn)

I went to college at the University of Michigan and part of my financial aid package was a work-study grant. So as a young freshman in 1984 interested in science and medicine, I obtained a position in a scientific research lab with Tadataka Yamada, who was then the chief of gastroenterology. My primary task was to wash glassware and make solutions.

But I was really interested in some of the experiments that were being done by the other scientists, and I asked lots of questions about what they were doing. The other scientists, including Dr. Yamada, picked up on my interest. Through their mentorship, I applied for a grant from the American Gastroenterological Association’s summer research fellowship to fund my own research project.

I won one of the awards, which meant that after my sophomore year, I got a promotion from washing glassware to running my own research project on regulation of gastric acid secretion. Our experiments led to some really interesting findings that we submitted to the organization for their annual meeting. Not only was it selected, but I was awarded the best student research project.

Because of that, I got to present at the annual meeting, which also happened to my first time attending an academic conference. At the age of 20 I delivered my first scientific presentation in front of over 1,000 people. My talk was at the plenary session, which meant it was in the biggest room with the most people in it. This was before PowerPoint and I had to make three sets of slides for each of the screens in the room.

I think I was too naive to know to be terrified! However, my mentor, Dr. Yamada, was nervous for me. Prior students who won this award were graduate or medical students, trainees and fellows. I remember he brought me up to the moderators and introduced me and made sure they knew I was an undergrad student so they wouldn’t ask me too many technical questions.

That experience sparked and inspired my interest in becoming an academic physician and in gastrointestinal diseases.

It also gave me a lot of self-efficacy. It showed me that through hard work and collaboration, I can do this type of work. But I saw that I could not have done it by myself. I worked closely with my mentors and other investigators in the lab in order to accomplish the work.

I also learned that not every experiment works. I found out why there’s the “re” in research. You end up redoing a lot. Not everything works out the way you planned, but sometimes you learn more in the failure than you do in the success.

Mary T. Hawn is the Stanford Medicine Professor of Surgery and chair of the Department of Surgery at Stanford Medicine.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Mary Hawn

Mary Hawn worked in a scientific research lab at the University of Michigan. Her research won her an award from the American Gastroenterological Association which she received (as pictured) at their annual meeting in 1985. (Photo courtesy of Mary Hawn)

I went to college at the University of Michigan and part of my financial aid package was a work-study grant. So as a young freshman in 1984 interested in science and medicine, I obtained a position in a scientific research lab with Tadataka Yamada, who was then the chief of gastroenterology. My primary task was to wash glassware and make solutions.

But I was really interested in some of the experiments that were being done by the other scientists, and I asked lots of questions about what they were doing. The other scientists, including Dr. Yamada, picked up on my interest. Through their mentorship, I applied for a grant from the American Gastroenterological Association’s summer research fellowship to fund my own research project.

I won one of the awards, which meant that after my sophomore year, I got a promotion from washing glassware to running my own research project on regulation of gastric acid secretion. Our experiments led to some really interesting findings that we submitted to the organization for their annual meeting. Not only was it selected, but I was awarded the best student research project.

Because of that, I got to present at the annual meeting, which also happened to my first time attending an academic conference. At the age of 20 I delivered my first scientific presentation in front of over 1,000 people. My talk was at the plenary session, which meant it was in the biggest room with the most people in it. This was before PowerPoint and I had to make three sets of slides for each of the screens in the room.

I think I was too naive to know to be terrified! However, my mentor, Dr. Yamada, was nervous for me. Prior students who won this award were graduate or medical students, trainees and fellows. I remember he brought me up to the moderators and introduced me and made sure they knew I was an undergrad student so they wouldn’t ask me too many technical questions.

That experience sparked and inspired my interest in becoming an academic physician and in gastrointestinal diseases.

It also gave me a lot of self-efficacy. It showed me that through hard work and collaboration, I can do this type of work. But I saw that I could not have done it by myself. I worked closely with my mentors and other investigators in the lab in order to accomplish the work.

I also learned that not every experiment works. I found out why there’s the “re” in research. You end up redoing a lot. Not everything works out the way you planned, but sometimes you learn more in the failure than you do in the success.

Mary T. Hawn is the Stanford Medicine Professor of Surgery and chair of the Department of Surgery at Stanford Medicine.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Emanuele Lugli

Emanuele Lugli interned for an award winning costume designer. (Photo: Getty Images)

In 1997 I spent a few weeks in Rome interning for costume designer Gabriella Pescucci.

But it wasn’t really an internship. Years ago, I had seen Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993), for which Pescucci won an Oscar, and naively wrote her a letter to express my admiration. To my surprise, she replied, as she did to every other message I sent her. After a couple of awkward meetings, during which I was too starstruck to make much sense, she accepted my sheepish request to work as her handyman.

So that summer, I went to Rome, where Pescucci was prepping for Chilean director Raul Ruiz’s adaptation of Marcel Proust’s Time Regained. I sleepwalked anywhere she went. I accompanied her to the milliner, who was tasked to cover dozens of wide-brimmed hats with fake bird wings, and quietly sat when she discussed makeup with famous actresses calling from Paris. I carried mannequins, heavy ball gowns whose trains I wrapped around my neck and giant rolls of tulle.

Mostly, however, I was a fly on the wall. I listened to Pescucci’s hopes of being hired for TV shows, which lasted longer and were better paid. (She eventually did work on The Borgias and Penny Dreadful.) I saw her managing deliveries and pickups of costumes for other productions –many outfits for Madonna’s Evita and Cate Blanchett’s Elizabeth had been made in her sprawling, beautiful shop, lined with books and autographs of stars.

At lunch, I listened to Pescucci’s verdicts on every single movie she saw – she went to the cinema every night – and to her advice of doing well at university since what the movie industry needed was culture, she said. She insisted that only a cultural whiz could produce something truly original in films, so she urged me to study history, history of art, and to devour as many books as I could. I took her words to heart and the following year I decided against majoring in film studies to read literature and philosophy instead.

But the change had not just been motivated by Pescucci’s speeches. In truth, I felt burned out. I could not believe that such a famous designer could be jobless for months, and that this flawlessly elegant woman, who wore electric jumpsuits and stilettos, could ever worry about money. Later on, I started seeing her advice almost as a form of rescue. Much of Pescucci’s work, after all, seemed to deal with logistics rather than ideas, but ideas – pyrotechnic ideas about narrative and visuals – were the very things that made movies so alluring to me. More than an internship, those few weeks in Rome made me reconsider my interests and my abilities in such a fundamental way that I don’t think I would have become a professor in art history had I not been pushed by such a formidable woman.

Emanuele Lugli is an assistant professor of art and art history in the School of Humanities and Sciences

Emanuele Lugli

Emanuele Lugli interned for an award winning costume designer. (Photo: Getty Images)

In 1997 I spent a few weeks in Rome interning for costume designer Gabriella Pescucci.

But it wasn’t really an internship. Years ago, I had seen Martin Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence (1993), for which Pescucci won an Oscar, and naively wrote her a letter to express my admiration. To my surprise, she replied, as she did to every other message I sent her. After a couple of awkward meetings, during which I was too starstruck to make much sense, she accepted my sheepish request to work as her handyman.

So that summer, I went to Rome, where Pescucci was prepping for Chilean director Raul Ruiz’s adaptation of Marcel Proust’s Time Regained. I sleepwalked anywhere she went. I accompanied her to the milliner, who was tasked to cover dozens of wide-brimmed hats with fake bird wings, and quietly sat when she discussed makeup with famous actresses calling from Paris. I carried mannequins, heavy ball gowns whose trains I wrapped around my neck and giant rolls of tulle.

Mostly, however, I was a fly on the wall. I listened to Pescucci’s hopes of being hired for TV shows, which lasted longer and were better paid. (She eventually did work on The Borgias and Penny Dreadful.) I saw her managing deliveries and pickups of costumes for other productions –many outfits for Madonna’s Evita and Cate Blanchett’s Elizabeth had been made in her sprawling, beautiful shop, lined with books and autographs of stars.

At lunch, I listened to Pescucci’s verdicts on every single movie she saw – she went to the cinema every night – and to her advice of doing well at university since what the movie industry needed was culture, she said. She insisted that only a cultural whiz could produce something truly original in films, so she urged me to study history, history of art, and to devour as many books as I could. I took her words to heart and the following year I decided against majoring in film studies to read literature and philosophy instead.

But the change had not just been motivated by Pescucci’s speeches. In truth, I felt burned out. I could not believe that such a famous designer could be jobless for months, and that this flawlessly elegant woman, who wore electric jumpsuits and stilettos, could ever worry about money. Later on, I started seeing her advice almost as a form of rescue. Much of Pescucci’s work, after all, seemed to deal with logistics rather than ideas, but ideas – pyrotechnic ideas about narrative and visuals – were the very things that made movies so alluring to me. More than an internship, those few weeks in Rome made me reconsider my interests and my abilities in such a fundamental way that I don’t think I would have become a professor in art history had I not been pushed by such a formidable woman.

Emanuele Lugli is an assistant professor of art and art history in the School of Humanities and Sciences

Matthew Jackson

Matthew Jackson unloaded boxes at a warehouse outside of Chicago. (Photo: Getty Images) (Image credit: Getty Images)

In the summers and winter breaks of 1980 and 1981 I worked at a catalog warehouse outside of Chicago. The job was simple – to unload 18-wheelers full of boxes of merchandise when they arrived, and to move the merchandise to shelves. It could be physical, as some products were much heavier than others. The merchandise was varied and so most of the unloading was by hand, and using pallets and hand-pulled hydraulic pallet trolleys.

The camaraderie kept the atmosphere lively and fun when we were hard at work. Indeed, the worst part of the job was the tedium – hours without a truck arriving nor with shelves to stock, sitting and waiting with endless boredom. It gave me a deep appreciation for the term clock-watching. Having friends to help pass that time was essential. The arrival of a truck always brought great excitement.

I recall the feeling of disappointment when seeing my first paycheck and realizing that a chunk of it was going to union dues, even though I was earning minimum wage. The job also came with periodic lie detector tests, as a nontrivial source of loss to the company was theft by its own employees. This was clear from the extensive list of questions that were asked about stealing or knowledge of any theft, sprinkled with detailed questions about drug use on and off the job. It was not a nurturing atmosphere.

Our lunches and dinners consisted of an assortment of fast-food available from nearby outlets – a steady diet of double hamburgers, tacos and oversized hot dogs. Even a young college student can be cured of any longing for fast food with an endless supply of it.

Looking back on the experiences, they are very dear to me. When I arrived at school in the fall, my appetite for knowledge and intellectual stimulation was well stoked. And my appreciation for the life that it has led me to has been greatly enhanced. There were positive aspects to the job; especially the friends who helped pass the time, and the fact that the job was completely left behind the moment I clicked out on my timecard. But the monotony, lack of accomplishment, poor work environment and bleak future made me sure that I wanted a career with varied tasks, intellectual stimulation, responsibility, personal growth and, most of all, where my efforts can make a difference.

Matthew O. Jackson is the William D. Eberle Professor of Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Image credit: Getty Images

Matthew Jackson

Matthew Jackson unloaded boxes at a warehouse outside of Chicago. (Photo: Getty Images) (Image credit: Getty Images)

In the summers and winter breaks of 1980 and 1981 I worked at a catalog warehouse outside of Chicago. The job was simple – to unload 18-wheelers full of boxes of merchandise when they arrived, and to move the merchandise to shelves. It could be physical, as some products were much heavier than others. The merchandise was varied and so most of the unloading was by hand, and using pallets and hand-pulled hydraulic pallet trolleys.

The camaraderie kept the atmosphere lively and fun when we were hard at work. Indeed, the worst part of the job was the tedium – hours without a truck arriving nor with shelves to stock, sitting and waiting with endless boredom. It gave me a deep appreciation for the term clock-watching. Having friends to help pass that time was essential. The arrival of a truck always brought great excitement.

I recall the feeling of disappointment when seeing my first paycheck and realizing that a chunk of it was going to union dues, even though I was earning minimum wage. The job also came with periodic lie detector tests, as a nontrivial source of loss to the company was theft by its own employees. This was clear from the extensive list of questions that were asked about stealing or knowledge of any theft, sprinkled with detailed questions about drug use on and off the job. It was not a nurturing atmosphere.

Our lunches and dinners consisted of an assortment of fast-food available from nearby outlets – a steady diet of double hamburgers, tacos and oversized hot dogs. Even a young college student can be cured of any longing for fast food with an endless supply of it.

Looking back on the experiences, they are very dear to me. When I arrived at school in the fall, my appetite for knowledge and intellectual stimulation was well stoked. And my appreciation for the life that it has led me to has been greatly enhanced. There were positive aspects to the job; especially the friends who helped pass the time, and the fact that the job was completely left behind the moment I clicked out on my timecard. But the monotony, lack of accomplishment, poor work environment and bleak future made me sure that I wanted a career with varied tasks, intellectual stimulation, responsibility, personal growth and, most of all, where my efforts can make a difference.

Matthew O. Jackson is the William D. Eberle Professor of Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Image credit: Getty Images

Zachary Manchester

Zachary Manchester was a software engineer in the Philadelphia area. In his spare time, he and his colleagues would go rock climbing together. (Photo courtesy of Zachary Manchester)

I have always been fascinated by airplanes and spacecrafts – I have loved airplanes since I could talk and I have dreamed about rockets since I was a little kid.

After finishing my sophomore year at Cornell University in 2006, I returned to the Philadelphia area where I grew up. When I learned from a neighbor that just a few miles from my childhood home was one of the main software providers to the space industry, I was immediately curious to find out more.

I literally rode my bike over one summer afternoon to ask for a job.

I ended up getting an internship at the company – Analytical Graphics Inc. in Exton, Pennsylvania. They develop the standard software package, called STK, that basically everyone who flies spacecraft uses.

A week or two into my internship, a software developer unexpectedly left the company and I ended up getting promoted into their role. As a college sophomore, I was essentially working a full-time job, writing code for a package that is still used today. I worked there the next summer too.

I realized at that point that I was basically doing what I would be doing once I graduated college – that was the career trajectory that I was on.

But over the summer I got to know the different people that worked there, including people who worked on the “actual rocket science” – the math and physics behind the code that calculated satellite orbits and rocket burns. I thought what they were doing was really interesting. And in turned out, they all had PhDs in aerospace engineering.

This was the first time I had interacted with people in a work environment who had PhDs. No one in my family had gone to grad school. Prior to that, the only people I met who had PhDs were my professors. But those engineers were the ones who really put it on my radar that graduate school was something I could do. Just from talking to them over lunch and during our breaks put me on a new career path in a field – aerospace and engineering – that I have always found exciting.

My summer job at AGI had a huge impact on my career and set me on the path that eventually led me to becoming a professor. For students thinking about summer internships, I would say to look for opportunities to take on real engineering responsibilities and don’t be afraid to take on something a little bit outside of your comfort zone.

Zac Manchester is assistant professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford University, a member of the Breakthrough Starshot advisory committee, and founder of the KickSat project.

As told to Melissa De Witte

Zachary Manchester

Zachary Manchester was a software engineer in the Philadelphia area. In his spare time, he and his colleagues would go rock climbing together. (Photo courtesy of Zachary Manchester)

I have always been fascinated by airplanes and spacecrafts – I have loved airplanes since I could talk and I have dreamed about rockets since I was a little kid.

After finishing my sophomore year at Cornell University in 2006, I returned to the Philadelphia area where I grew up. When I learned from a neighbor that just a few miles from my childhood home was one of the main software providers to the space industry, I was immediately curious to find out more.

I literally rode my bike over one summer afternoon to ask for a job.

I ended up getting an internship at the company – Analytical Graphics Inc. in Exton, Pennsylvania. They develop the standard software package, called STK, that basically everyone who flies spacecraft uses.

A week or two into my internship, a software developer unexpectedly left the company and I ended up getting promoted into their role. As a college sophomore, I was essentially working a full-time job, writing code for a package that is still used today. I worked there the next summer too.

I realized at that point that I was basically doing what I would be doing once I graduated college – that was the career trajectory that I was on.