Philosopher Michel Serres, a well-known public intellectual in France and a Stanford professor emeritus of French, died from lung cancer on June 1 at a hospital in France. He was 88.

Serres, who taught in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences for nearly 30 years, worked on the philosophy of science, where he explored subjects like death, ecology and time. A member of the prestigious French Academy (Académie Française), Serres was charismatic, intellectually brilliant and a philosopher who connected with a broad audience, according to his friends and colleagues.

Serres sought to achieve a big-picture narrative about human culture and historical change, said Stanford Professor of Italian literature Robert Harrison. Trained as a mathematician, Serres could command a slew of subjects, including law, thermodynamics, evolution, ethics and geology.

“Serres was one of the greatest humanists of the early 21st century,” said Harrison, the Rosina Pierotti Professor of Italian Literature in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “He showed us the way to a new kind of encyclopedic humanism. He mastered an immense number of subjects, and his values were deeply rooted in the human condition. He shared Stanford’s vision of a broad and creative interdisciplinary approach to knowledge.”

A prolific writer who wrote 73 books in total, Serres’ favorite philosophical topics involved ecology and human cultural evolution in our contemporary digital age, Harrison said.

Mathematician turned philosopher

Born in Agen, France, in 1930, Serres initially studied mathematics at the Naval Academy until he read Simone Weil’s Gravity and Grace. He then left the academy and turned to philosophy, receiving a doctorate with a thesis on Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s philosophy in 1968.

Serres became a full professor at Stanford in 1984. He was also a professor for 27 years at the Paris-Sorbonne University, where he served as the chair in the history of science in 1969. He also taught at the University of Vincennes and University of Clermont-Ferrand.

Serres was an optimist who had a positive outlook about the capabilities of future generations in the era of the internet and smartphones, Harrison said.

“Serres believed that digital gadgets, social media and internet interconnectivity promised a new chapter in our history – equivalent of the invention of the printing press,” Harrison said.

Serres’ notable books include The Parasite (1980), Hominescence (2001), and a series of volumes about communication called Hermes and Thumbelina (2012). Serres was elected into the French Academy in 1990, becoming one of its only 40 life members. Previous members of the academy include famous French writers and thinkers like Voltaire and Victor Hugo. Serres was awarded the Meister Eckhart Prize in 2012 and he received the Dan David Prize in 2013.

Feeling free at Stanford

Serres was especially famous in France, where people would recognize him every time he would go out in public. But at Stanford, which Serres would visit to teach twice a year, he felt liberated from his fame in France, said Audrey Calefas-Strebelle, Serres’ former research assistant.

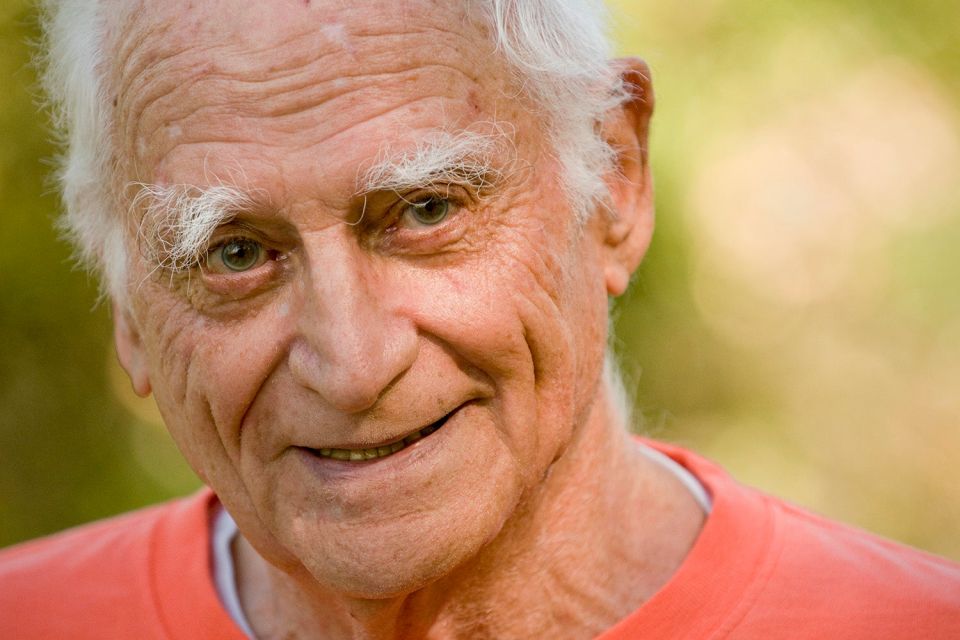

Serres felt free from fame when he visited Stanford, according to a former research assistant who regarded him as a mentor. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

“Michel told me many times about how he felt so free when he came to Stanford,” said Calefas-Strebelle, “It was so easy for him to go everywhere and not be observed, like he was in Paris.”

Calefas-Strebelle said she pursued her doctorate degree partly because of Serres’ encouragement. She met Serres in 2001 when she took up a lecturer job at Stanford’s Department of French and Italian.

“He was my intellectual father,” said Calefas-Strebelle, who finished her doctorate at Stanford in 2012 and is now an associate professor of French at Mills College in Oakland. “He created a community at Stanford that was very special. He was so much more than just a professor – he touched our lives.”

When he came to Stanford, Serres stayed with his longtime friend and colleague René Girard, the late renowned Stanford French professor.

Serres would hold weekly two-hour philosophy lectures that were filled with students and people from outside of Stanford. The lecture hall would rarely have enough chairs for every attendee, Calefas-Strebelle said. Those lectures also inspired most of Serres’ books, such as Malfeasance: Appropriation through Pollution?

Philosopher of the people

During the last decade of his life, Serres also produced a podcast and had a regular radio spot in France, reaching millions of people.

“Michel was a philosopher of the people,” Calefas-Strebelle said. “He was able to reach out to everyone – those educated and not.”

Harrison said he became friends with Serres on his first day at Stanford in the 1980s.

“Whenever Serres arrived on campus, he brought a certain kind of joy and happiness to people,” Harrison said. “He was always full of positive emotion and charm.”

He said Serres encouraged him to think outside of academic boxes. Thanks to Serres’ influence, Harrison said his second book was “completely different thanks to him” from his first book, which was more academic.

Harrison said he and Serres would often go for long walks or attend different social events on campus and in San Francisco.

“He had this benevolent laughter,” Harrison said. “His presence had a kind of happy glow to it.”

Serres is survived by his wife, Suzanne, and four children, Hélène Weis, Jacques Serres, Pascal Serres and Jean-François Serres, as well as his 11 grandchildren, Claire, Irène, Jean-Baptiste, José, Lise, Madali, Marie, Pauline, Raphaël, Thérèse and Victoire, and his 11 great-grandchildren.

A memorial service honoring Serres will be scheduled at Stanford for the fall quarter. More details will follow.