Just about every California school kid knows the story of the First Transcontinental Railroad, which connected the Eastern Seaboard with the Pacific Coast and was completed 150 years ago this week.

Leaders of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroad lines meet and shake hands in this iconic photograph taken by Andrew J. Russell on May 10, 1869. (Image credit: Stanford University Archives)

The story goes that on May 10, 1869, the Central Pacific Railroad’s tracks from the west were connected to the Union Pacific Railroad’s tracks from the east in Promontory Summit, Utah. University founder Leland Stanford completed the First Transcontinental Railroad with a last tap of a mallet on a ceremonial gold spike.

In the words of Hilton Obenzinger, associate director of the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford, the railroad completion was the first mass media event in the United States. After the connection was made, telegraph messages celebrating the accomplishment went out, launching festivities nationwide.

That’s because the railroad was not simply a new mode of transportation, according to James Campbell, the Edgar E. Robinson Professor in United States History. The railroad was also a way of transforming space and time – a transformation that necessitated, for instance, the creation of standardized time zones. It was the quintessential 19th‑century innovation, reflecting power and promise and replacing the brute strength of human labor with ingenuity.

“The Transcontinental Railroad has a place in the U.S. imagination not because of what it actually did, but because of what Americans imagined it to be: a symbol of national progress, of American imagination and intrepidity,” Campbell told a recent symposium assessing the railroad’s impacts and sponsored by the Stanford Historical Society and Stanford Continuing Studies.

Good and bad

As time passed, romantic visions of the First Transcontinental Railroad have given way as hindsight revealed both its good and bad elements. The railroad is credited, for instance, with helping to open the West to migration and with expanding the American economy. It is blamed for the near eradication of the Native Americans of the Great Plains, the decimation of the buffalo and the exploitation of Chinese railroad workers.

Either way, Stanford is forever linked to the First Transcontinental Railroad through its founders, who built the university memorializing their son using the fortune they had earned from the Central Pacific Railroad and the Southern Pacific Railroad.

“There is no question that this is truly a transformative event, not only for Stanford University, but also for the nation,” said Laura Jones, director of heritage services, university archaeologist and president of the Stanford Historical Society, which has spearheaded events marking the anniversary.

“This story has Leland Stanford right in the middle of it,” she said.

In addition to the Stanford Historical Society, departments across campus have sponsored lectures, book celebrations, exhibitions and performances noting the anniversary to shed light on the railroad’s legacy and show how institutions can reconcile problems of the past with the values of today.

Business opportunists

Separating fact from fiction was an objective of the recent symposium assessing the railroad’s impact. Scholars, including historian Richard White, shared, for instance, that the First Transcontinental Railroad was not an economic or migration boom. The Central Pacific Railroad barely remained solvent. It was, instead, the Southern Pacific Railroad, which eventually took control of the Central Pacific Railroad, that deserves credit for creating economic expansion as it leveraged speed to monetize California produce.

Student body Vice President Dianne Goldman (later U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein) views the gold spike that Leland Stanford used to connect the First Transcontinental Railroad. After years in a San Francisco Wells Fargo Bank vault, the “Last Spike” was delivered by armored car in 1954 to the recently reopened Stanford Museum. (Image credit: Stanford News Service)

In addition, White suggested that the California Pacific Railroad’s Big Four – Leland Stanford, Collis Potter Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker, also known as the Associates – were not railroad entrepreneurs, but rather business opportunists who recognized the fortune to be made through the government land grants and subsidies supporting construction.

They were not “railroad men,” said White, who is the Margaret Byrne Professor of American History in the School of Humanities and Sciences and author of Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. So, they faced considerable challenges after the momentous event in Utah. For instance, the route the railroad followed “went from nowhere to almost nowhere,” White said. In addition, the transportation of goods at the time was better suited to steamships. By the 1890s, the Central Pacific Railroad was, White said, virtually worthless.

The railroad was, however, evidence of the promise of the relatively nascent profession of civil engineering, according to engineering historian Paul Giroux, who described the unprecedented scale of construction – often in challenging conditions – of the First Transcontinental Railroad to members of the Stanford Historical Society at their recent annual meeting.

“Building a railroad requires billions of steps, but they all have to be done correctly,” he said. “The logistics to me of this railroad are just mind-blowing.”

Despite the odds, the Big Four had a “talent for survival,” White said. The tales of their shady railroad business deals, as well as those of the Union Pacific Railroad, have lingered. For instance, some cheeky students in the 1970s voted to name Stanford University’s athletic teams the Robber Barons.

But it’s important to recognize another – more positive – side to the Big Four, and especially Stanford, according to Jones.

Stanford, she said, was a visionary who believed in the promise of California. He was a born salesman motivated by an undaunted optimism in California’s future. He was politically savvy and would serve both as California governor and U.S. senator, helping ensure support for the railroad.

“This is a story that starts with ambition and hope,” she said. “You cannot deny that there were some sharp business practices. It was a ruthlessly competitive business – and that was not unique to the Associates.”

Jones said that Stanford approached every venture – business or otherwise – with a commitment to improvement. That approach can be seen in the California vineyards he created, the racehorses he raised and the Palo Alto farm he nurtured and – ultimately – the university he founded.

Fading memories

For many years, Jones said, the university was deeply associated with the railroad. Students came from across the country to study railroad engineering. The Stanford University Course Bulletin of 1891, for instance, references the courses Economic Theory of Railroad Location and Railroad Operation and Management. A 1924 Stanford Daily article announced an exhibition at the Stanford Library on the California railroad from its earliest days, featuring maps, illustrations and copies of telegraphs.

As further evidence of the connection, the ceremonial Gold Spike became part of the university’s archival treasures. Its name has since lent heft to an annual alumni recognition called the Gold Spike Award. In addition, the Gov. Stanford locomotive, the Central Pacific’s first locomotive, once took up an unlikely residence wedged between columns in the rotunda of what is now the Cantor Arts Center.

The Gov. Stanford locomotive, brought to campus in 1899, in the 1960s went to the California State Railroad Museum, where it is on prominent display. (Image credit: Stanford University Archives)

Jones said the Gov. Stanford locomotive was moved to the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento in the 1960s, where it is available for public viewing. When it left campus, she said, the memory of the university’s relationship to the First Transcontinental Railroad began to fade.

But the legacy of the Big Four has not faded. Oddly, all of their family lines eventually died out. Much of their remaining fortunes were invested in philanthropic gifts. Besides Stanford University, the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens in San Marino has its origins in the railroad. Collectively, the Big Four also established the Sacramento Library Association.

“Had their children lived, the institutions probably would not have been created,” White said.

Scholarly pursuits

Since 2012, the university’s connection to the railroad has been revitalized as Stanford researchers have led a remarkable international and interdisciplinary effort to tell the story of the Chinese migrants who constructed the First Transcontinental Railroad.

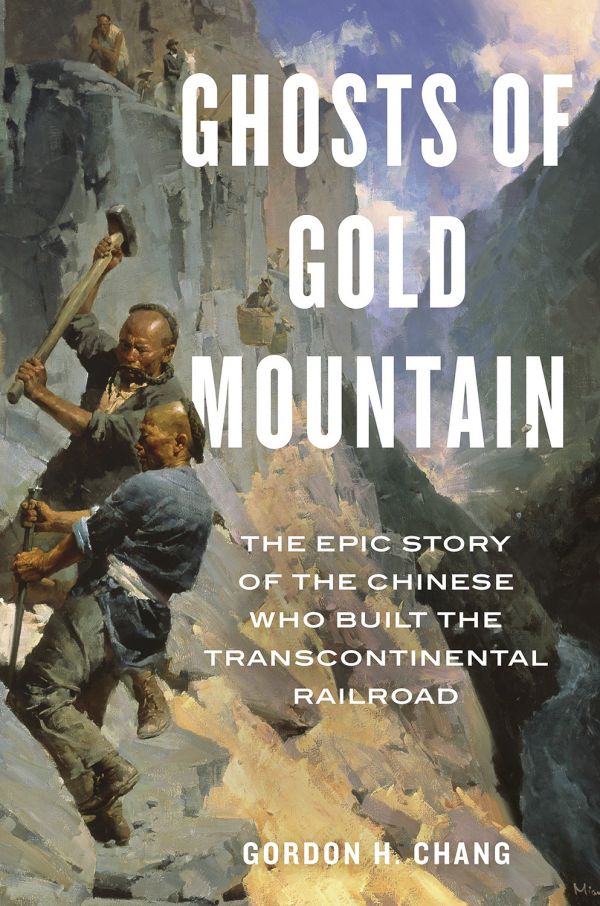

An early April event debuted two newly published books resulting from the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project: The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad and Ghosts of the Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad.

The scholarly project, headed by Gordan Chang, the Olive H. Palmer Professor in the Humanities, and Shelley Fisher Fishkin, the Joseph S. Atha Professor in Humanities, recovered and reinterpreted the history of the Chinese railroad workers chiefly responsible for the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. More than 100 scholars in North America and Asia joined efforts to tell a story that had largely gone untold for more than a century. In addition, the Archaeology Network of the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, headed by archaeologist Barbara Voss, collected materials that Chinese workers left behind in the United States and in China.

The project has revealed that the Chinese workers, many of whom subsequently went to build the Canadian Pacific Railroad, lived much more complicated lives and had much more complex social networks than previous research suggests. In the immediate years after the railroad construction, their work was highly praised until anti-Chinese sentiment and fear of immigrants led to the Exclusionary Act of 1882.

Other events

Another Stanford program associated with the 150th anniversary of the First Transcontinental Railroad is a film series, sponsored by the Stanford Historical Society, the Bill Lane Center for the American West and Stanford Continuing Studies, that explores the story through the eyes of Hollywood. On May 13, for instance, the series will feature the 1968 film Once Upon a Time in the West, a so-called “spaghetti Western” directed by Sergio Leone.

Stanford Historical Society and the Bill Lane Center will also sponsor a reception at the Leland Stanford Mansion in Sacramento in conjunction with area alumni. Historian David Kennedy will speak.

On May 10, there will be a train and railroad open house at Special Collections in Green Library from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.

In addition, the David Rumsey Map Center presented a pop-up exhibition of the maps created by railroad engineer Theodore Judah. The maps, on loan from the California State Archives, measure 2.5 feet wide and 66 feet long and have been scanned to make them available worldwide.

The Stanford Libraries also is offering online an array of materials related to the anniversary and, in particular, to the Chinese railroad workers. Included in the collection are Alfred A. Hart photographs commissioned by Leland Stanford, railroad maps from the David Rumsey Map Center and oral histories of Chinese railroad worker families.

In addition, the Stanford Symphony Orchestra is one of the 13 American orchestras that will be presenting Zhou Tian’s Transcend!, a new work commemorating the 150th anniversary. The performance will take place in Bing Concert Hall on Nov. 15 and 17, 2019.